Hundreds of street vendors descended on City Hall on Thursday to demand Big Apple leaders make significant reforms to the way the industry is regulated.

The vendors, organized by the Street Vendor Project, say that New York’s smallest small business owners are stymied by an outdated regulatory framework and preventing individual businesses, and the industry writ large, from reaching their fullest potential. They also are subject to ruinous enforcement by police, they say.

About 20,000 vendors work the streets of the five boroughs, according to the Street Vendor Project. But most of them say they are forced to toil in the shadows due to a decades-old city law capping the number of merchandise vendor licenses at 853, with few exceptions. 11,926 applicants are currently sitting on a merchandise license.

As for food vendors, in 2021 the City Council passed legislation creating nearly 4,500 new vendor licenses to be distributed over the next decade, but the Street Vendor Project says the city hasn’t even gotten started yet. That waiting list is home to about 10,000 people.

The mayor’s office did not respond to an inquiry seeking comment.

The mostly immigrant population representing the bulk of street vendors can either rent an existing license or risk fines of up to $1,000, as well as the confiscation of their wares for working without a license, or with a license but without a location-based permit.

Ana Carreto, who sells tamales in Jackson Heights, Queens, said she and her husband have a license to sell, but have no chance to get a permit because the waiting list is closed to everyone except military veterans and people with disabilities.

“If we don’t have it, we don’t have a way to survive,” said Carreto, who often brings her young son to work with her as they are also stuck on a waitlist for childcare. “That’s our job.”

The family’s business has been raided thrice by the NYPD, who on one occasion tossed all of their merchandise in the garbage.

“We don’t need to have the police behind us,” said Carreto. “We are people trying to work, to have a place to stay.”

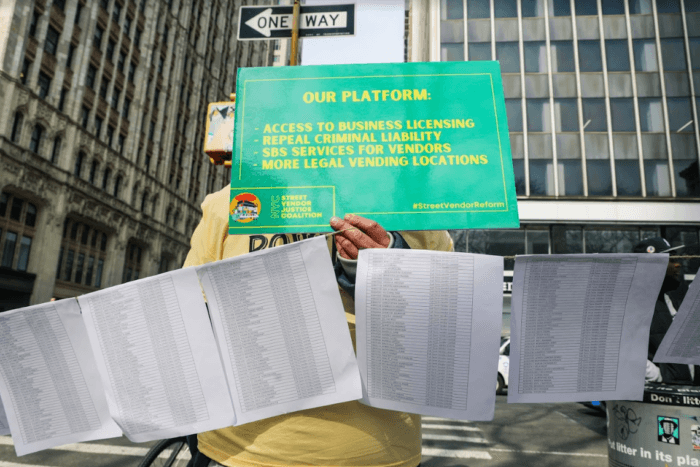

Vendors say they want to ensure that licenses and permits are plentiful and accessible for all entrepreneurs, to have street businesses regulated by the Department of Small Business Services like brick-and-mortar establishments, and to remove the NYPD entirely from the regulatory framework.

Bronx Councilmember Pierina Sanchez, whose father sold peanuts on the streets of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic and mixtapes in the Boogie-Down, said she plans to introduce legislation to that effect.

“I call on all 51 City Councilmembers and all of our state legislators to attend to this platform here,” said Sanchez. “These four bullet points that summarize what the street vending community is after. Dignity. Respect. The ability to be a part of the city, just like anyone else.”

The call to action comes after a call by City Councilmember Sandra Ung for a crackdown in her Flushing district, which is replete with vendor activity.

At the rally, Public Advocate Jumaane Williams drew a line between the treatment of street vendors and deliveristas, both mostly immigrant workforces widely relied upon in the city, but subject to exploitative working conditions.

“We often like to benefit from things but not help the people who are providing that benefit,” said Williams. “So whether it’s deliveristas or vendors, we want to get their labor, we want to get the thing that they provide, but we want to continue an abusive structure in which they provide it. That’s unfair.”

“No one is expendable, and that includes our vendors,” the Public Advocate continued. “So we must provide a system and structure that is less abusive to them, the way that we would want to be treated at our jobs.”