This is the third part in amNewYork Metro’s series “Still Racing to Deliver,” a follow-up to our five-part series exploring the proliferation of quick-commerce grocery services in New York City. In “Still Racing to Deliver,” we catch up with the industry, which has changed rapidly in the last ten months, and how it has impacted the city, local businesses, and more. Click here to read the first, second, and third installments.

Over the last year, a brand-new industry has swept through New York City and the world: quick-commerce grocery delivery service.

Combining the convenient delivery offered by InstaCart and Fresh Direct with the speed of newer delivery companies like DoorDash and UberEats; app based grocery delivery companies promising to deliver groceries and other goods within ten or fifteen minutes or order quickly grew in scale and in wealth. New York City welcomed a host of new venture-capitalist back companies like Gorillas and Getir, and with them dozens of micro-warehouses and hundreds of delivery workers.

Of course, where there’s a booming new industry, there must be new regulations. It wasn’t long before local politicians and workers unions started to eye 15-minute grocery delivery service more critically.

Among the first politicos to take issue with these companies was then-Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer. Last fall, just a few months into the reign of quick-commerce grocery delivery, she and her staff started noticing new micro-warehouses, or “dark stores,” the center of quick-commerce grocery delivery, popping up in Manhattan.

The windows of the dark stores were papered over, they weren’t open to the public, and, since the business was entirely app-based, customers couldn’t pay with cash.

“It turned out that all over the city they were popping up,” she said. “It was like, what is this? And I must admit, I had never heard of them.”

She knew storefronts were required to have transparency in their front windows, and that New York City requires that retail businesses must accept cash payments. In a year that had forced many small businesses to close, Brewer worried these new, possibly-illegal businesses would threaten local grocery stores and bodegas.

In an October 2021 letter to commissioners of various city agencies, including the Department of Buildings and the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, Brewer expressed her concerns.

“I am concerned that these services compete with existing supermarkets, bodegas and other food and beverage establishments, and occupy spaces that are now no longer available to the public,” she wrote. “While there continue to be food deserts in Manhattan, these companies are not serving those areas; instead, most are opening where there are already many grocery options.”

She asked the agencies to investigate the warehouses, figure out whether or not they complied with local laws, and work out an enforcement mechanism.

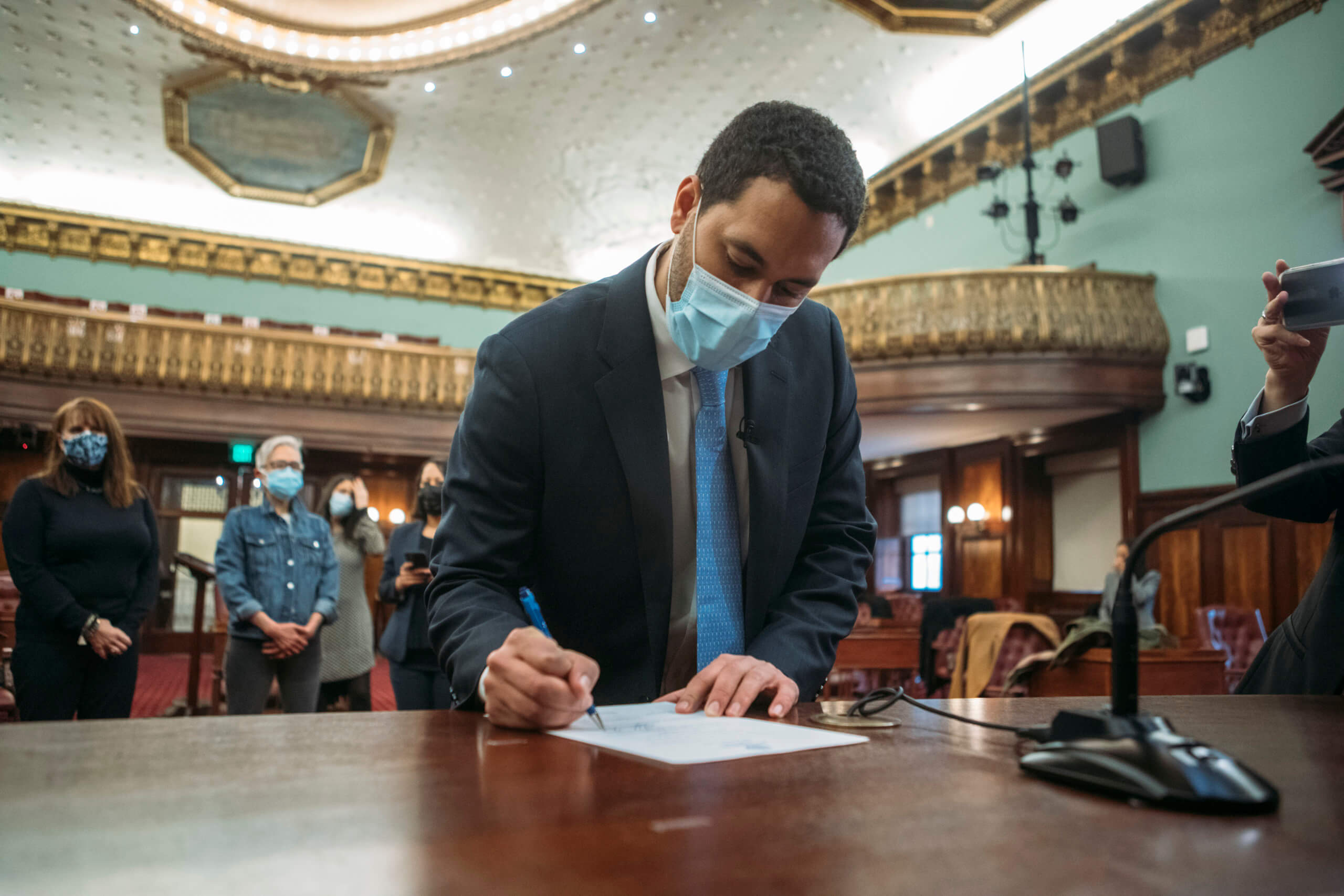

Six months later, in her new role as City Council member and part of the council’s Committee on Consumer and Worker Protection, Brewer re-upped her concerns in another letter, this one co-signed by council Speaker Adrienne Adams and a number of her other colleagues representing districts across the five boroughs.

The letter asked the DOB to take “immediate action” to regulate dark stores operating against zoning regulations and in potential violation of other city laws. Brewer’s staff provided DOB and DCPW with a list of dark stores they had identified in Manhattan, and, in August, DCWP said it had sent cease-and-desist letters to the companies not complying with the city’s cash laws and would “follow-up to issue notices of hearing for illegal activity, as necessary.”

“And then of course, are they legal at all? I never really got an answer from the City Planning Commission, to be honest with you,” Brewer said.

Enforcing worker safety

Brewer’s colleagues, Manhattan Council Members Julie Menin and Christopher Marte, felt another aspect of 15-minute grocery delivery they felt was in need of regulation: worker safety.

In 2021, the council passed a suite of bills promising new protections for contracted delivery workers, or “gig workers,” who delivered for companies like UberEats and DoorDash but were not formally employed by them. The package included bills that enforced minimum pay standards and gave delivery workers the right to decide how far they were willing to travel per delivery.

But it quickly became clear those laws wouldn’t protect workers at the new grocery delivery apps — the legislation was aimed specifically at contracted workers, and almost all of the quick-commerce apps employed their couriers either full or part-time.

Plus, the needs of the grocery delivery employees were different — they received a salary and most were provided with supplies like branded e-bikes, bags, and uniforms — and their employers claimed to be “employee-first.”

Delivering food in New York City is a dangerous job — delivery workers are regularly attacked and struck by vehicles while they’re out riding, and many worried the stress of a promised 10-or-15 minute delivery was putting couriers at more risk.

“From my experience, and from a lot of my constituents’ experience, these are dangerous labor practices, and create a lot of risk for the worker and for the people on the sidewalk,” Marte told amNY Metro. “I believe that this whole industry should be regulated, so I thought this legislation was a good first step into doing that.”

He and Menin in July introduced three bills in the council: one that would limit the weight of grocery deliveries, since the couriers were most often hauling them in backpacks while on a bicycle; a second that would require the services to drop their 15-minute promise for the safety of the workers; and a third that would require grocery delivery services acquire a license from the city to operate.

“What I feared was that this was going to become like Uber or Lyft, where the city waited for long for them to add any oversight, that they became too big, they became too big, it’s almost impossible to do anything to contain them,” Marte said.

Getting in on the ground floor, while the services were still fighting amongst themselves to establish the biggest market share, would give the city a solid foundation to demand the companies play by their rules.

Keeping up with a rapidly-changing industry

The number of quick-commerce grocery delivery companies in the city has been slashed dramatically since their heyday last fall — and those who stuck around — like Gorillas, Getir, and GoPuff — quickly wised up and changed some of their practices.

Gorillas axed their 15-minute promise earlier this year and Getir does not promise exact delivery times, executives from both companies told amNY last month, and workers are encouraged to prioritize their safety over the speed of deliveries. Gorillas started taking the opaque paper out of its front windows, and Getir’s distribution centers are open to the public for shopping.

“We’ve seen a lot of them change their practice — not all of them — we’ve seen a lot of them change their marketing schemes, add more protections for their workers, so we know this industry is going to try to be as flexible and adaptable as possible,” Marte said.

Even as some companies have invited their customers inside in theory, both Brewer and Marte said when they attempted to shop at dark stores, they were asked to wait at the counter while an employee grabbed their items, and Brewer said she had trouble paying with cash — though she was eventually able to do so.

Marte and Menin hope to hold hearings on their proposed bills this fall and get them voted on by the end of the year or in early 2023. After that, they’ll see what else has changed in the industry that might need to be regulated, he said.

Brewer said some constituents who live in apartments directly above dark stores worry about the e-bikes stored inside —the lithium batteries that power them are infamous for catching fire, and the city has considered banning them from public housing developments after a spate of fires last summer.

“I think we will check in with consumer affairs again, because I don’t want them to start popping up,” Brewer said. “Because they are disruptors, in the worst sense of the word.”

She chose not to sign onto Menin and Marte’s trio of bills because she doesn’t want quick-commerce grocery businesses to exist in the city at all, she said, regardless of what regulations or laws they’re supposed to follow.

“I don’t know how you legislate it, I didn’t put my name on it only because the cops can’t figure out what to do with anybody not following the rules of the road,” she said. “I don’t think they’re ever going to follow the law, I think they should be in the warehouse district.”