Finding that leasing documents, proof of state benefits and income certifications submitted to a landlord weren’t sufficient on their own to establish proof of residency — and thus gain succession rights to a Mitchell-Lama apartment designated for low and middle income residents — the state’s highest court ruled against the brother of a terminally ill musician who lived in Hell’s Kitchen and died in 2020.

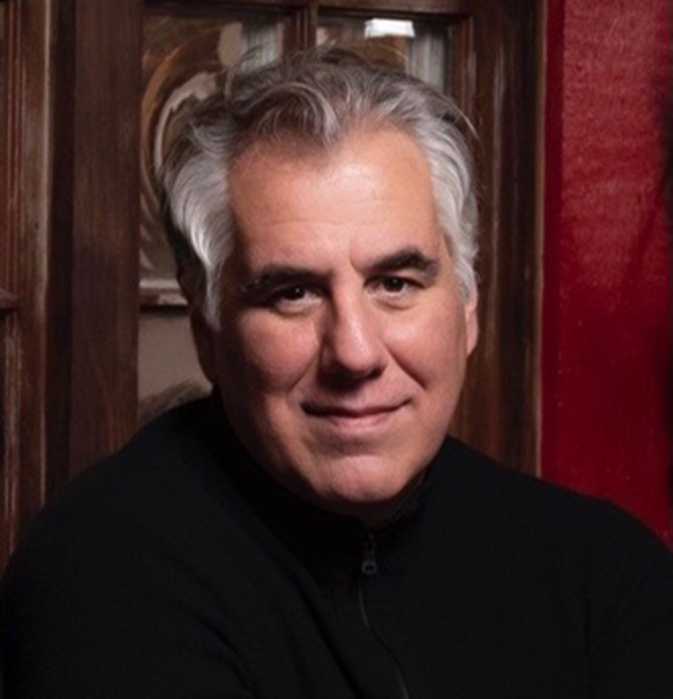

In a 5-2 ruling, the majority found that 65-year-old Kermit Mantilla, who moved from Miami, Florida, to New York City in 2018 to care for his terminally ill older brother, jazz percussionist Raymond Mantilla, had not provided enough documentary evidence to prove that the Hell’s Kitchen apartment was his primary residence for the year before to Raymond Mantilla’s death, March 21, 2019 to March 21, 2020.

Kermit Mantilla’s attorney, Dennis Fan, called the decision disappointing. He said it was “regretful” the court didn’t grapple with the fact that its decision would result in Mantilla’s eviction.

When people deal with the death of a family member, he said, realistically, they aren’t “stacking up documents to apply for succession rights.”

“I think the court misses the context of how real people operate,” Fan said. “I don’t think it even acknowledges that they’re just kicking a New Yorker out onto the streets who otherwise cannot afford to live in New York … It’s a really harsh way to judge people who are low-income, who are at the end of a loved one’s life.”

The brothers’ only source of income was Social Security, a collective $1,400 a month while they lived together in the affordable housing unit. After Raymond Mantilla died, Kermit Mantilla submitted SNAP and other benefit program documents addressed to him at the Manhattan Plaza apartment, and bank statements for his brother’s bank account, which he had power of authority over, also sent to the Manhattan Plaza address, as proof that the apartment had been his primary residence for the past year.

Kermit Mantilla also provided signed income recertification and leasing documents submitted to Manhattan Plaza to inform landlords he was living in the apartment and his income should be considered when determining the apartment’s rent, which is based on resident salaries, along with Raymond Mantilla’s death certificate, dated March 21, 2020, which identified him as the informant and the Manhattan Plaza apartment as his address.

However, the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development and courts took issue with Mantilla having a Miami home address, him maintaining a Florida driver’s license during the co-residency period, not receiving any bank statements on a personal bank account at the address and only submitting two SNAP-related pieces of mail addressed to him during the one-year period immediately preceding his brother’s death. Mantilla also did not submit other documentation that could have proved his residency, like New York state tax returns, voter registration, motor vehicle registration or other documents filed with public agencies.

“[The] petitioner failed to meet his burden to produce documents establishing that the apartment was his primary residence, and he failed to provide a necessary component of the succession rights application,” Judge Anthony Cannataro wrote for the majority.

Cannataro’s opinion, with which Judges Michael Garcia, Madeline Singas, Caitlin Halligan and Chief Judge Rowan Wilson concurred, affirmed an appellate court that overturned a trial court ruling granting Mantilla the succession rights the housing authority had denied.

Judges dissent

In a dissent, Judge Jenny Rivera wrote she believed Mantilla’s documentation was sufficient and the majority focused too heavily on documentation not provided. The overall facts of the case, she said, establish it would be irrational to believe Mantilla was not primarily living in the Hell’s Kitchen apartment during the final year of his brother’s life.

Kermit Mantailla served as his brother’s primary caregiver, taking him to medical appointments, bathing him, caring for his physical needs and paying for transportation, groceries and other necessities with their limited funds. The suggestion that the caretaker was living in Florida would mean he’d had to travel back and forth between Miami and New York City while living on only a few hundred dollars a month in government aid.

“Given petitioner’s demanding caretaking responsibilities, and that he is a senior citizen of limited means, dependent on meager Social Security and other governmental benefits to survive, it was simply irrational for HPD to conclude that the Mitchell-Lama apartment was not his primary residence during the last year of his brother’s life, when petitioner was most needed to assist his brother,” Rivera wrote, with Judge Shirley Troutman concurring.

The dissenting judges said the city shouldn’t have denied Mantilla succession rights “all because he was missing a few recommended pieces of paper,” while he provided “numerous other documents establishing his residency.”

They took particular issue with the fact that the Manhattan Plaza landlords raised the rent on the apartment after Mantilla moved in because he added his Social Security income to the income recertification documents, yet still determined that Mantilla couldn’t legitimately prove he primarily lived there for a year.

“For Manhattan Plaza to collect rent money from a low-income resident like [Kermit Mantilla] for more than a year, only to turn him out after his brother’s death, runs directly contrary to the Mitchell-Lama statutory scheme and its remedial purpose of preventing displacement after a family member’s death,” Rivera wrote.

Amici react

Edward Josephson of Legal Aid Society, which filed an amicus curiae in the Mantillas’ case, called the decision “depressingly more of the same.”

While neither he nor Fan, Kermit Mantilla’s attorney, thought the outcome would have an impact on other apartment succession cases, if the case had been decided in Kermit Mantilla’s favor, it would have created more favorable conditions for those in similar situations.

“I think a contrary decision would have been a big improvement for our clients, and would have made the agency be less callous and reflexive in rejecting people’s claims,” Josephson said. “Unfortunately, this decision puts a blessing on the status quo, which is a harsh, harsh status quo.”

Fan criticized the city for appealing the New York Supreme Court’s decision in Mantilla’s favor even though the building’s landlord accepted the decision.

“I think that’s a sad reflection of how we use city resources: The landlord is okay with the tenant staying, and the city is out here, essentially on its own, making the decision that it wants to try to get somebody evicted,” Fan said.

When asked for a comment on the decision and about why it decided to appeal, the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development only said it believed the Court of Appeals “properly applied the law,” and that it was “satisfied with its decision.”

Fan said he hoped incoming Mayor Zohran Mamdani’s corporation counsel would shift the city away from practices like this. Mamdani hasn’t officially announced who will fill that position, but Steven Banks, who served as former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Department of Homeless Services Commissioner, and law professor Ramzi Kassem are rumored to be top contenders.

Fan and Josephson said legislation and regulatory fixes could rebalance the standard judges use when considering whether to grant someone succession rights, including a statute that people shouldn’t be penalized if they don’t submit each one of the many documents listed as possible means to prove their residency.

The city could align its practices for determining Mitchell-Lama apartment succession rights with those of the state, which Fan said are clearer and tend to look at cases in totality, rather than “dinging” people on not having a specific document.

In Mantilla’s case, for example, while some documentation, like letters approving him for SNAP and reduced heating costs, fell outside of the one-year window immediately preceding his brother’s death, it was only by a matter of weeks — and he was collecting those benefits through the year he lived with his brother.

“If you start to get your SNAP benefits in February 2019, it’s not like you’re not still collecting your SNAP benefits in March and April and all the subsequent months,” Fan said.

Josephson added that another potential fix may be for a person’s initial appeal hearing after the Housing Preservation and Development Department denies their succession application to be an oral, in-person hearing where they can explain their situation in detail..

“I think for low-income people particularly, it’s very helpful for them to tell their story in their own words, instead of just relying on pieces of paper,” Josephson said. “A lot of the determination in Mr. Mantilla’s case was about credibility, whether the court believed that he was living with his brother … These credibility determinations, historically, are made face to face.”

If Mantilla had been able to explain his situation thoroughly, in his own words, from the start, Josephson said it may have changed the outcome of his initial appeal and would have “strengthened” his case as it moved through the courts.