There are not many political insiders like former Governor Andrew Cuomo’s long-time friend and election lawyer Martin Connor who are still active in the tumult of New York City politics.

At 80, Connor, the former state senate minority leader, has been battling over ballot access for at least 54 years. The breadth of his experience makes him a specialized resource within the city’s small bar of election lawyers. It also means he has been around long enough to have witnessed the start of Cuomo’s career when he took a pro-bono role in his father Governor Mario Cuomo’s administration.

“Andrew spent maybe a year or two on the second floor [of the governor’s office], as a dollar-a-year advisor to his father and I think Mario told him, ‘No, go out and make a living.’ And he went out, got a legal job,” Connor told amNY Law.

Connor’s scholarly understanding of election law began as a political hobby and developed throughout his 30-year term in the state senate, where he would regularly volunteer his services as an election lawyer for his Democratic senate colleagues. Eventually he began representing candidates all over the state and at every level from presidential races to governor, mayor, and all the way down the ballot.

The deep knowledge of the electoral map of the entire state, not just New York City, from his law practice and time as minority leader, bolstered his relationship with both Mario and Andrew Cuomo.

As a client, Andrew Cuomo has been “on-again-off-again” for Connor, but he’s been a friend throughout his whole career, Connor said. When he first met the former governor, Connor’s impression “was that he was a hard worker and a real go-getter and a fighter.”

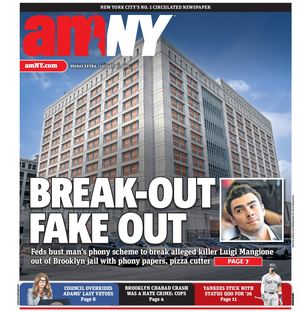

Though he lost to Zohran Mamdani in the Democratic New York City mayoral primary, Connor was optimistic about Cuomo’s independent bid to overtake Mamdani in the polls and win the general election. He said Cuomo has found a style in this second stretch that plays to his strengths more than the Rose Garden strategy he used to keep the press and voters at a distance during the primary, which “came off cold and distant” and “didn’t work — big time.”

“Total opposite strategy,” Connor said of Cuomo’s current approach. “And look, he’s very good on the street, shaking hands.”

As far as his own background, Connor’s career in politics began in election law. It started with his first gig for his reformist, anti-Vietnam War political club in Brooklyn in the days before election law had expanded as a practice into a full-fledged career path.

“Nobody else has been doing it since 1970,” he said, adding that he has no plans to retire “until something happens that convinces me or other people that I can’t do it anymore.”

In conversation, Connor has a tendency to delve into political lore. He recounted the finicky computer mainframe in a temperature-controlled room where legislators “put booties on” to view their election districts in the 1980s. He pulled all-nighters to overturn multiple primary races in a single season. In 1992 he ended up working to help Ross Perot get on the New York ballot as part of his race against former President Bill Clinton. (Connor maintains he got the job through Democratic sources, and that Clinton preferred Perot as his foil. “The beauty was I was doing a good thing for the party,” he said.)

His passion for the process has become a commodity on the campaign trail. He described his election law practice as a comprehensive legal service for campaigns, which is different from many other election lawyers who specialize in a single area. While his practice includes bread-and-butter areas like ballot access and campaign finance, he also acts as a “general counsel,” doling out legal advice about a wide variety of issues.

“I of necessity sometimes weigh in on strategy, particularly, if there are things in election law [where] people say, ‘Is it legal if I do this?’” he said, distinguishing the role from the work of a political strategist.

In its scope, his career has paralleled huge changes to election law. In his first case as an election lawyer, he fended off ballot challenges for a group of insurgent candidates from the Brooklyn Democratic machine. To do so, as a fresh-faced 25-year-old lawyer, he had brazenly subpoenaed a judge, who had flouted ballot petition regulations, and got the party lawyers to drop their challenges. Celebrating his victory, Connor recalled asking another lawyer who had helped him with the case, “Anybody ever pay you to do this? They were like, ‘Nah, nobody ever pays you to do this. And so the world changed.”

As campaigns and regulations have continued to expand, he argues that the practice of election law has grown beyond the seasonal limits in the months before a primary.

“There are all kinds of ongoing legal issues,” he said.

He had a front row seat into the creation and aftereffects of the New York City Campaign Finance Board in the late 80s, which he has described as a “big win for democracy,” even if he has his criticisms.

Known in the legislature as a crusader for good government, Connor has argued that his work is grounded in the principle of improving small-d democracy in ballot access and minimizing the influence of big money in local politics.

As a senator he passed legislation to make ballot access easier, but his record of boosterism gets a little more complicated in his role as an election lawyer, which necessarily entails working for the political establishment in an era where independent expenditures keep breaking new records.

In representing Cuomo, for instance, he has found himself working for a campaign backed by the largest super PAC ever created in a New York City mayoral campaign.

Fix the City, a PAC led by Cuomo’s close allies, raised $25 million in the primary to promote the former governor’s candidacy and bombard Mamdani with negative political ads. Though the arrangement set a race-altering advantage for Cuomo, Connor insists that as it pertains to his job, it’s entirely beyond his control.

“I had nothing to do with that, nor did my client. Obviously thanks to the Supreme Court’s [Citizen United decision], you can’t stop anybody from doing it…” he said, referring to the federal case that lifted restrictions on super PACs. “Everybody has an independent expenditure. Mamdani has a second one opened up. It’s really the Wild West.”

According to the NYCCFB, however, the campaign’s bulwark against PAC supporters wasn’t strong enough. The board ultimately withheld over $700,000 in matching funds from Cuomo after finding that an ad that Fix the City released was not done independently of the campaign.

Asked whether he had a role in advising the campaign on this issue, Connor replied “I don’t want to comment on that.”

The incident plays into what Connor argues is a major flaw of the NYCCFB system: lack of expedited judicial review. A candidate can be denied public funds just before an election, but the legal challenge to that decision often doesn’t conclude until after the election is over, effectively crippling their campaign. Connor argued that these cases should be treated with the same urgency as ballot access cases, which get top priority in the court system.

“There has to be a way to challenge their decisions within a matter of a couple weeks before an election,” he said.

The NYCCFB did not respond to a request for comment.

Though Connor said that he got into election law as a means of empowering more candidates to run for office, once he got into office he used to get criticized for helping his colleagues with pro bono election law work. In some cases, that meant keeping challengers off the ballot.

“The press… got on my case. The New York Times said, ‘Well, you do election law, you kick people off the ballot.’ Yeah, sometimes, but realistically, 95% of what I do is get people on the ballot, and keep them there safely,” Connor said.

Back in the day, Connor said politics was more collegial and less partisan, unlike the strict ideological lines that he said characterizes the state legislature today. He recalled a time when he would organize dinners with Republican colleagues and find common ground. Likewise, he had a good relationship as a state senator with Mario Cuomo when he entered the governor’s mansion — at odds with the infighting between current Governor Kathy Hochul and the legislature.

But from where Connor now sits, the old-fashioned congenial approach to politics has worked out. He exclusively represented Democrats when he was an active legislator (with the exception of Perot) but has found himself occasionally representing a Republican in his practice, often referred to him by a former Republican colleague.

“I’m a lawyer. I’m not a political operator,” he said. “Once upon a time it was different. I’m a recovering politician.”