Residents of SoHo and NoHo’s artist live-work apartments are asking the United States Supreme Court to overturn a recent 6-1 decision from New York judges attaching over $250,000 in fees to many of their lofts when selling or passing them down to family.

The fees stem from a 2021 city rezoning plan, which, in its current form, requires just over 1,600 loft residents to obtain a city permit to turn their artist live-work spaces into residential apartments if they want to sell or pass them down to family. However, it attaches an $100 per square foot fee, to be paid into a city Arts Fund, to those permits. For lofts that frequently exceed 2,500 square feet, residents say that adds up fast

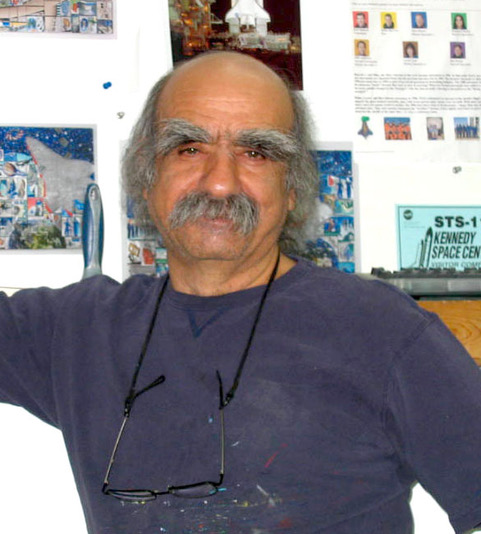

“I’m not sure what we’ll do now,” said 80-year-old artist Zigi Ben-Haim, who’s lived in his SoHo loft since 1979. “I have no idea how we’ll deal with this. It’s frightening.”

Ben-Haim said he bought his loft for about $40,000, obtaining the money for a down payment by selling a large work of art to the SoHo Hotel, then turned the space from a run-down factory to a livable home, putting up walls and installing electrical wiring and flooring himself. He, and other artists with similar stories amNewYork Law spoke with, called the mandate any buyer or heir to their lofts pay into a city Arts Fund for permits — totaling over $250,000 for many units — to convert the live-work apartments into a purely residential one, as well as pay for renovations to ensure it fits into the city’s residential code, “unfair.”

“We put all our energy, our blood into these lofts,” Ben-Haim said. “Then, when we finally achieve something … the city grabs it back again from the artist.”

Today, many lofts in the neighborhood frequently fetch between $1.5 million to $4 million or more when sold, but artists say the renovations and permits are a significant financial barrier because they expect the costs will eat into profits they’d need to relocate — and they’ve spent years putting the majority of their resources into the upkeep of their buildings, many over a century old. For those looking to pass the apartment down to a child instead of sell, like SoHo artist Margo Margolis, there aren’t any sale profits at all to balance out the costs, making them even more daunting.

The New York Court of Appeals’ majority, led by Judge Jenny Rivera, disagreed with the loft residents’ arguments that the fee was an unfair taking of their property, as the government was requesting a fee attached to a permit, not requesting to take any piece of real estate directly.

“The City’s new rezoning plan does not alter the zoning of plaintiffs’ property or diminish their rights in any way,” Rivera writes. “Instead, it permits plaintiffs … to convert their units, at any future time, to unrestricted residential use upon payment of a one-time ‘nonrefundable’ Arts Fund fee.”

Rivera held that the fee was voluntary, as it only had to be paid if a person chose to sell or pass on the apartment, and it allowed the loft owners to transform it into a different type of unit — from an artist live-work space into a residential space — so the owner’s property interests weren’t being imposed upon.

“Petitioners…do not seek to simply make use of their property in a way currently prohibited by the City. Rather, petitioners seek to transform the property into a wholly different type of interest,” Rivera wrote. “Petitioners may desire a property interest in a more valuable and less restrictive form, and they may want it without strings attached, but the opportunity to relinquish one form of property to acquire another, in exchange for a monetary payment to an arts fund, is not a taking.”

Rivera was joined by Chief Judge Rowan Wilson and Judges Madeline Singas, Anthony Cannataro and Shirley Troutman, as well as Judge Caitlin Halligan in a concurring opinion.

Margolis, 78, told amNewYork Law she felt the court had misunderstood the challenge the fee presented to residents, particularly older artists who she said didn’t have vast savings and had been living in the lofts for decades.

She said she “didn’t know” if her son would be able to afford the fees required for the loft, which he grew up in, to shift into his hands after her death.

“For me, and for other artists who are some of the early pioneers of SoHo, the question of ‘How do you pay that fee?’ is really hard, especially those of us that are older,” Margolis said.

Christopher Kieser, the Pacific Legal Foundation attorney representing these artists and others in the live-work apartments, called the recent ruling from New York’s highest court disappointing and shocking, particularly because it overturned an unanimous appellate court decision abolishing the fee scheme.

Kieser believes the New York Court of Appeals ruled contrary to both Supreme Court precedent and rulings from other states’ high courts — which makes him confident judges on the country’s top bench will grant his writ of certiorari, or official petition for review.

His argument, drawing primarily on three frequently-cited Supreme Court precedents referred to as Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, Dolan v. City of Tigard and Koontz v. St. Johns River Management District, is that requiring the artists to pay a permitting fee into the city’s Arts Fund — which would provide grants to cultural organizations beneath 14th Street via the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs — is an unconstitutional taking of property in violation of the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause, which protects property owners from government overreach.

“Nollan and Dolan are limits on the government’s power to extract property from land use permit applicants,” Kieser said. Nollan requires there be a nexus, or direct association, between what the government asks for in exchange for a permit and the permit; Dolan requires there be a proportional impact between what’s asked for and the changes that would be caused by altercations, renovations or building the permit enabled.

The Arts Fund fee fails both of those tests, Kieser argued.

“In this case, the demand to contribute into the Arts Fund has nothing to do with any interest that the city might assert as for why they would want to deny these permits,” Kieser said. “The only real rationale for requiring the residents to pay into the Arts Fund was because they need something now from the government, a permit, and they could be extorted.”

He argued a later case, Koontz, extended the Nollan and Dolan tests to include instances where the government demands money — like in this Arts Fund fee case — not just real property, in exchange for a permit.

However, the majority in New York’s Court of Appeals wrote that, because the city government isn’t requesting the fee here in lieu, or instead of, a transfer of private property, it’s not subject to the Nollan and Dolan tests. If imposed outside the permitting process, Rivera wrote, the fee wouldn’t constitute a compensable taking, so it does not matter whether it passes those tests.

That’s incorrect, or at the very least, unsettled, according to Kieser.

“I think there’s a split in how to interpret Koontz between states’ [highest] courts,” Kieser said. “The North Carolina Supreme Court held that Koontz is not limited to in lieu fees, so there’s a clear split between [New York and North Carolina] courts.”

That’s why he believes it’s so critical for the Supreme Court to review and overturn the decision: there will continue to be a lack of clarity in how courts should decide Fifth Amendment and land use permitting cases, likely resulting in state judges ruling opposite to how the Supreme Court intended them to.

“In Koontz, the demand was for Mr. Koontz to contribute money to improve government land miles away from his land in exchange for developing a small portion of his land,” Kieser explained. “And the court said, ‘No, Nollan and Dolan do apply, even though the demand was for money and not for real property,’ and that’s exactly what we have here, yet the Court of Appeals said they don’t apply.”

Judge Michael Garcia, the court’s singular dissenting voice, agreed with Kieser’s argument.

“The government’s demand for property from a land-use permit applicant must satisfy the requirements of Nollan and Dolan even when . . . its demand is for money,” Garcia wrote. “[Here], it did not pass that test … The City may not use the permitting process to force petitioners to host Shakespeare in their loft, nor to fund Shakespeare in the Park.”

It’s rare for the Supreme Court to grant writ of certiorari reviews, but Kieser feels like this petition has a strong fighting chance due to the lack of clarity between state courts on how the Koontz decision should be applied.

Even if he’s right, however, a new decision for these over 1,600 SoHo and NoHo residents — some artists who share similar stories to Ben-Haim and Margolis, others non-creatives who’ve bought lofts in recent years — is well over a year away.

However, Christopher Marte, the neighborhood’s council member, is looking towards quicker legislative solutions, like introducing a City Council bill that would eliminate or lower the permitting fee — currently at $100 per square foot, set to rise by 3% each year — to a “negligible” amount.

“We’re working to figure out what we can do on the council side,” Marte said. “It’s still fresh, because this decision just came out a few days ago, but hopefully we’ll have something much more concrete in the coming weeks.”

Marte, who’s been helping the residents fight the fee on the legislative side for years and called the Appeals Court decision a “crushing blow,” said he plans to talk with the community and other council members to figure out the most effective pieces of legislation to introduce in upcoming council meetings.

Artists like Ben-Haim and Margolis said they’re hopeful one the City Council or the Supreme Court is able to grant them relief from the fee. In the meantime, they remain in limbo, uncertain of what to do and bitter that the city is asking them to pay into the Arts Fund when they feel they built SoHo’s reputation as an arts mecca with their bare hands.

“Artists are the ones that built SoHo in the beginning,” Ben-Haim said. “I hope they come to their senses and give us a break.”