The Whitney has once again raised the curtain on history with Sixties Surreal, a landmark exhibition that does not so much revisit the 1960s as it reanimates them. Featuring more than one hundred artists—Arbus, Kusama, Bearden, Chicago, Warhol, Hammons, Bourgeois, Johns, Marisol, Ringgold, Whitten, and others—the show offers a thrillingly revisionist portrait of an era when art did not merely reflect civil unrest and cultural upheaval, but sought to transfigure them into enduring beauty.

Encountering the remarkable Martha Edelheit before her work Flesh Wall with Table (1965) was a moment of rare serendipity. The painting itself is a striking testament to the human body as landscape—flesh arranged like terrain, both alluring and unsettling, punctuated by the austerity of a table that becomes anchor and stage. It is erotic and clinical at once, collapsing the distance between object and observer. Standing with Edelheit before this work felt like standing at a hinge of history, where the freedoms of the body and the struggles of the age intersected in unapologetic color. That encounter alone made my month.

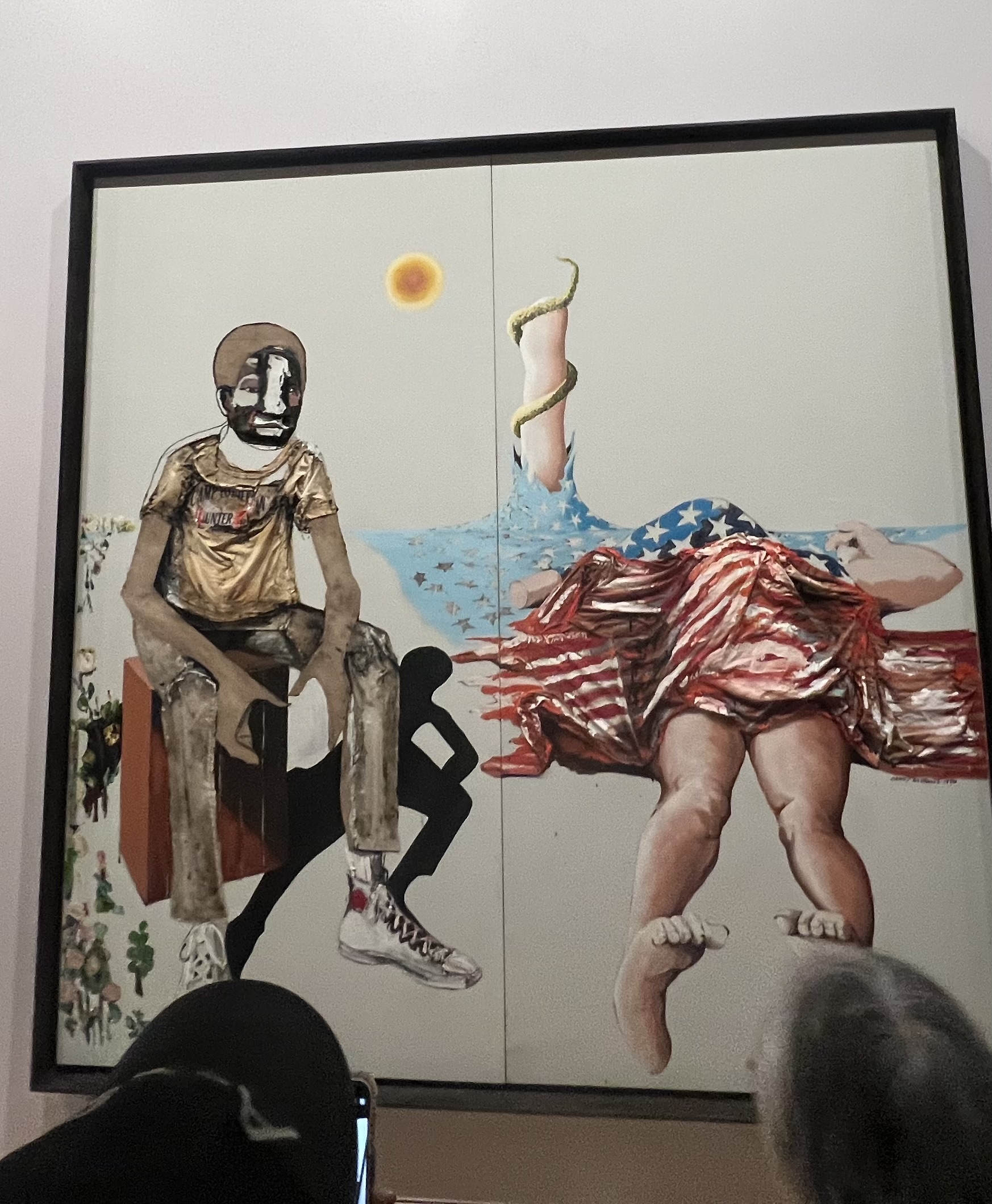

The sculptures throughout the exhibition startled with their urgency, bending metal and stone into the shapes of protest and longing. Yet Benny Andrews’ No More Games caught me by the throat. The taut American flag, paired with those curled toes, formed a juxtaposition of method and color so precise and unflinching it left me breathless. The piece distilled the contradictions of its moment—patriotism and protest, order and disarray, allegiance and revolt—into one unforgettable image.

What lingered most was the resonance between that chaotic decade and our own uncertain age. The questions of the sixties—about freedom, authenticity, and belonging—still rattle our cultural bones. Influencers may imagine themselves as the heirs of the hippie vanguard, yet the comparison falters. The hippies pursued transformation, experimented with consciousness, and sought utopian unity. Influencers cultivate engagement, align with sponsors, and measure impact in metrics. Their communes exist on digital platforms, their mantras distilled into hashtags, their revolutions monetized in real time. Bop houses attempt the ecstatic energy of communes, though with cover charges, wristbands, and curated playlists—a kind of packaged transcendence delivered in neon, efficient and fleeting, rather than communal and transformative.

The Whitney opening itself carried its own pleasures. Flowing cocktails and trays of crisp crabcakes circulated like punctuation marks to the evening’s conversations. No one hosts art parties with the effortless balance of gravitas and glamour that the Whitney achieves. Dialogue flowed as smoothly as the wine, reminding us that art, at its best, is both communion and celebration.

Sixties Surreal is not merely an exhibition. It is a conversation between past and present, a reminder that chaos repeats yet art endures. These works do more than depict upheaval; they interpret it, transform it, and return it to us as something enduring. In that alchemy lies the true purpose of art, and the reason the Whitney remains essential: to reveal our time refracted through the lens of another, and to remind us that redemption, if it comes, often comes draped in the surreal.

Check out the exhibition and more information at whitney.org.

Follow @aaluxuryatelier for more art and luxury.