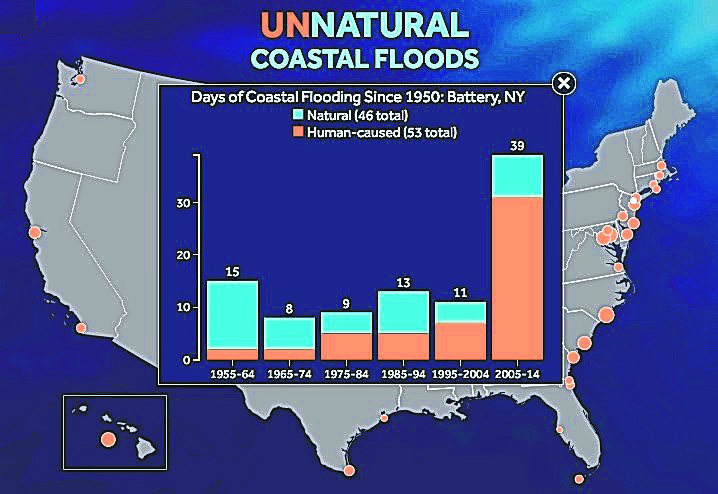

This chart shows the dramatic increase in flooding Downtown that can be attributed to sea-level rises caused by man-made climate change, according to report by Climate Central.

BY YANNIC RACK |

Downtown Manhattan has seen one of the steepest increases in the country of flooding caused by sea-level rises resulting from man-made climate change, according to a recent study, and experts say the problem will only get worse, even as post-Sandy flood protections for the area remain largely unfunded.

A report by New Jersey-based non-profit Climate Central found a dramatic spike in recent years in the amount of flooding in the area around The Battery in recent years attributable to human-induced increases in sea level.

One of the authors of the report described how a small increase in sea level can turn otherwise harmless weather into street-swamping floods.

“When a street floods with saltwater, and you can’t drive home, or you have to sandbag your store, human instinct looks for the nearby cause: it was a very high tide, or a strong wind blew from the wrong direction,” said Benjamin Strauss, vice president for sea level and climate impacts at Climate Central. “But what if the tide or the wind were not enough to tip the balance? What if the waters would not have crossed the last lip, the critical threshold, without a few inches of boost?”

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a group of scientists found that the worsening of tidal flooding in coastal communities in the U.S. is largely due to greenhouse-gas emissions and will only increase over the coming decades.

In a separate report analyzing the findings, researchers used the data to calculate that around three-quarters of the flood days now plaguing cities along the East Coast would not be happening if it wasn’t for sea-level rise caused by human emissions. In the 1950s, heightened sea levels tipped the balance in less than half of flood days. And in some places, sea-level rise accounts for a dramatic increase in flooding.

The Battery was one of eight areas studied which saw such flooding double since the 1950s.

Even though sea level rise contributes only a limited amount to the huge surges accompanying storms like Sandy, the impact can nonetheless make a critical difference, according to Strauss.

“A higher starting level means that the same tide, the same storm surge, goes higher than it otherwise would have,” said Strauss. “Tide gauges dotting our bays and beaches have been recording this shift.”

Tide gauges show that sea levels have risen about five inches in the 65 years since 1950, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Climate scientists predict that sea levels could surge by more than twice that amount over the next 35 years.

And while tidal flooding is already making life miserable for residents in places like Miami Beach and Charleston, S.C., local leaders warn that the threat in Lower Manhattan could have dire consequences unless the city speeds up its flood protection program — and finds the money to do so.

“This report only highlights our concern,” said Catherine McVay Hughes, chairwoman of Community Board 1, who has been advocating for more flood protection Downtown long before it was revealed last month that the city has yet to commit any funding to Lower Manhattan south of the Brooklyn Bridge. “Whether or not the city is ready, this is happening,” she said.

Earlier this year, the city won $176 million in a federal competition for its program to protect Lower Manhattan from future storms, but a letter released by the mayor’s office last month showed that the money had been earmarked by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Renewal for the Two Bridges area — leaving CB1 empty-handed.

“The city’s application included the entire project, from Montgomery Street down and around to the north end of Battery Park City, and only a portion of that was funded by HUD,” said Michael Shaikh, a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency. “We intend to work with all of our affected communities to find ways to fill the resulting funding gaps,” he said, adding that the city was nonetheless moving ahead with the 18-month design and community engagement phase for the entire project.

But the Lower Manhattan Protect and Connect project is estimated to cost upwards of $600 million alone. In addition to the $176 million from HUD going to Two Bridges, only $115 million have been raised so far by the city and state — and most of that money hasn’t been allocated yet.

“We still don’t know where the $100 million from the city is going,” said Hughes. “And there’s still a huge funding gap even if we get that money for CB1.”

This year’s preliminary city budget did not allocate any funding for Downtown storm protection, which had been one of CB1’s main capital-budget requests.

In addition, Shaikh told CB1 members this week that HUD would also have a say in where the city’s $100 million will be used, because those funds were leveraged as part of the federal competition.

Pressured by members of the board’s Planning Committee at its monthly meeting, Shaikh said that the mayor’s office was “not hiding behind HUD” and that he would come back in May with an answer on how much of the money was going to CB1.

“We’re on the same page,” he assured the committee, whose members were anything but satisfied with that answer.

“There just doesn’t seem to be any urgency,” Hughes replied angrily. “There is no money coming from City Hall. We’re just ‘investigating’, and ‘looking for’ [it].”

Another project, called East Side Coastal Resiliency, spans the Lower East Side shoreline from Montgomery St. north to E. 23rd St. and was awarded $335 million through another federal competition two years ago. Construction on that project is scheduled to start next year and could take until 2022, according to the city.

Although specific plans are not finalized, most of Lower Manhattan will eventually be protected from storm surges by a system of sea walls, movable flood barriers, pumps, and a levee system at its southern tip.

The proposals also call for flood-proofing public housing developments, mostly in the Two Bridges area, and integrating the water barriers into plazas, parks and retail areas. The mayor and city officials have emphasized that sections of both projects will go online before all of the work is completed.

But climate change won’t wait, say the researchers.

Experts now forecast that the ocean could rise as much as three or four feet by 2100, if man-made emissions were to continue at a high rate over the next few decades. In a major setback for President Obama’s efforts to combat climate change, the Supreme Court just last month blocked the administration’s program to regulate emissions from coal-fired power plants.

The regulation, issued last year by the Environmental Protection Agency, aims to cut emissions from power plants by a third by 2030 by mandating that states make major cuts to greenhouse-gas pollution by closing hundreds of heavily polluting plants — the country’s largest source of such emissions — and increasing reliance on wind and solar power.

The court order was not the final word on the case, however, which will likely return to the Supreme Court after an appeals court deals with a challenge from dozens of states and corporations.

CB1’s Hughes said the ultimate goal is to lower emissions — but in the meantime the threat of severe flooding like after Superstorm Sandy, which claimed two lives in Lower Manhattan and caused billions of dollars in damage, continues to increase.

“We want to prevent flooding in the first place,” she said, “but we have to make sure our shoreline is safe either way.”