2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, which instantly killed around 100,000 residents in both Japanese cities and claimed the lives of approximately 90,000 and 166,000 people in Hiroshima and 60,000 to 80,000 in Nagasaki in the months following the bombings. The effects of the nuclear apocalypse affected residents for years to come, with children being born with congenital disabilities and survivors suffering from various forms of cancer at higher-than-normal rates.

This week, the United Nations (UN) is holding its third Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The Treaty was adopted on July 7, 2017, at the UN and entered into force on Jan. 22, 2021. It not only abolishes nuclear weapons, but it also calls for reparation for radiation victims and the remediation of contaminated environments.

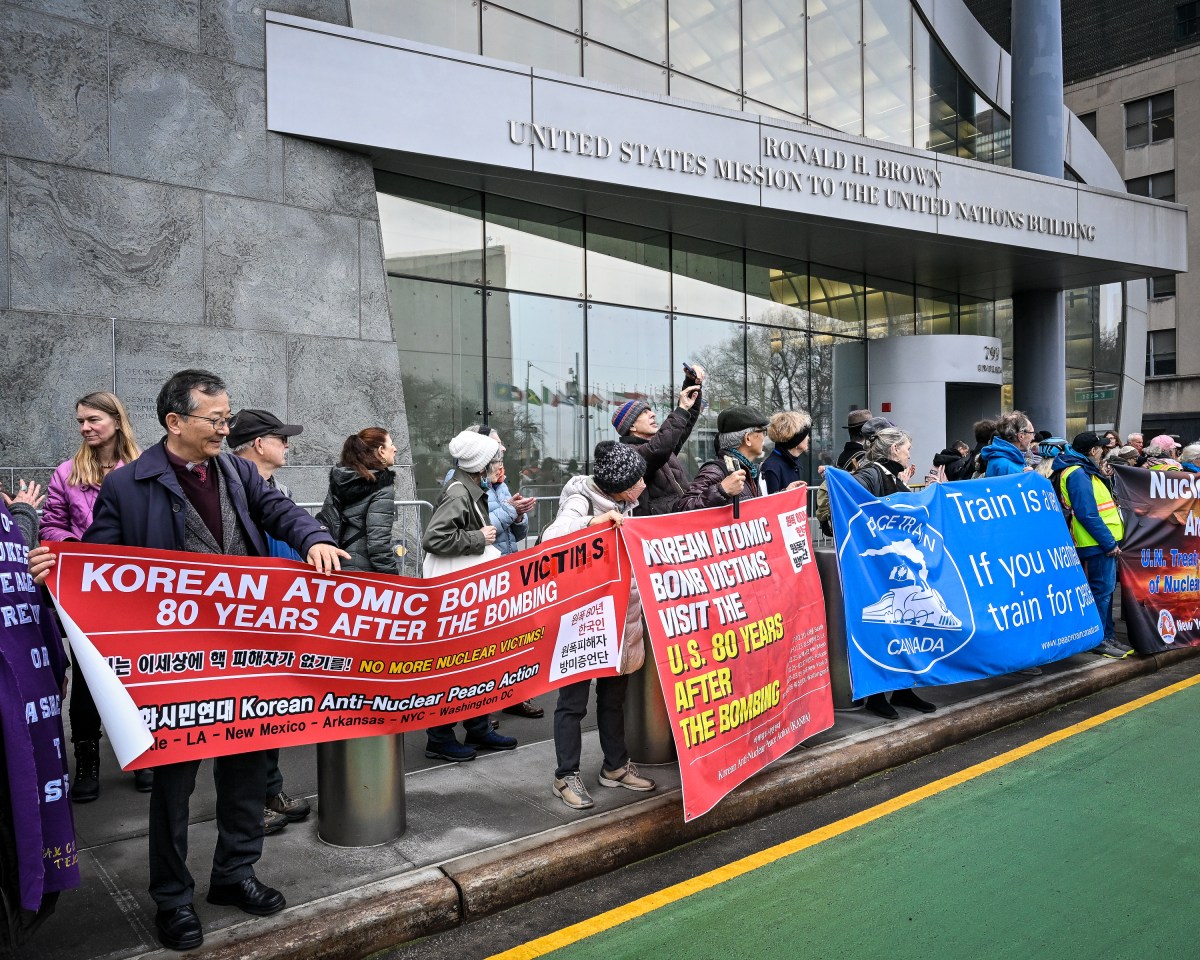

While scientific experts, representatives of governments who have ratified or signed the Treaty, members of non-governmental organizations, and parliamentarians gathered at the UN to discuss the TPNW, a coalition of anti-nuclear groups rallied across the UN building on 1st Avenue in Midtown Manhattan on March 5 before marching to the U.S. Mission to the UN.

Currently, the TPNW has 94 signatories, and seventy-three nations and states have ratified the Treaty. However, the United States, Canada, Japan, and most European countries have not signed the Treaty, and the activist groups, including the Manhattan Project for a Nuclear Free Word, Peace Action Fund of New York State, NYC Metro Raging Grannies, and Peace Train Canada, to name a few, called on them to attend the meeting and sign the Treaty.

Rally speakers pointed out that the mining of uranium and testing of nuclear weapons intersect with many social justice, health, and environmental issues.

Isaiah Mombilo, chairperson of the Congolese Civil Society of South Africa, talked about the connection between Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the Shinkolobe mine was the source of most of the uranium used for the bombs. Workers were forced to mine a few thousand tons of the ore without protective clothing, unaware of the deadly health implications. The U.S. secured 1,200 tonnes of Congolese uranium, which was stockpiled on Staten Island.

“Nothing [has been] cleaned, nothing [has been] resolved, and the people of that area sit are suffering [from] cancer, suffer with malformation, and the serious problem [has] never been fixed by UN [or] by any agents of that nuclear disaster,” Mombilo said.

Jiro Hamazumi, a Hibakusha – a Japanese word for survivors of the atomic bombings- urged nations to create a world free of nuclear weapons, and Dr. Lee Taejae, a second-generation South Korean Hibakusha, pointed out that the atomic bombings also claimed the lives of thousands of Korean slave laborers.

Setsuko Shimomoto’s father, Tobei Oguro, was a crew member of a tuna fishing boat and exposed to the radiation fallout -or “ashes of death”- of a U.S. hydrogen bomb test over the Bikini Atoll in Marshall Island in 1954. Oguro was diagnosed with stomach cancer and bile duct cancer and died in 2002.

Shimomoto joined a lawsuit filed in Kochi District Court and is now the chief plaintiff, seeking reparations from the Japanese Government.

“The Japanese Government has a responsibility to ratify the TPNW [and] recognize victims of black rain in Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as fishers affected by nuclear testing, and inform the world of the dangers of radioactivity,” Shimomoto said with the help of a translator.

Since 1945, there have been 2,121 nuclear tests conducted in more than 60 sites around the world, including New Mexico. Leona Morgan, an Indigenous activist from New Mexico, said the United States failed Indigenous nations, calling the mining of uranium “nuclear colonialism.”

Between 1944 and 1996, millions of tons of uranium were extracted from Navajo land, which includes Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. Hundreds of mines are abandoned but continue to pollute drinking water and soil, and radioactive waste has not been remediated. Many Navajo people have died of kidney failure and cancer, illnesses linked to exposure to radioactive material.

“Right now, the United States is investing millions into this uranium mill to develop rare earth elements, and these will be used for so-called renewable energies and new technology. This is where the fuel for nuclear comes from. It comes from our land. They use uranium for both weapons and energy,” Morgan said.

Morgan called the push for tripling nuclear energy by 2050 as a solution to combat climate change a “lie.”

“Nuclear is not a solution to climate change. It is a lie. They are lying to us. Nuclear is not a solution, and we must stop it,” Morgan demanded. “[Nuclear] is killing our people.”

Robert Croonquist won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2017 with his team members from the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). Croonquist told amNewYork Metro that on a local level, they were working with NYC Comptroller Brad Lander to divest the New York City pensions and finances from nuclear weapons productions.

“It is always important to get together in community with people from around the world because the work is very difficult, and you feel very isolated and you get exhausted. And to be with other people doing the work makes you feel like you can go on,” Croonquist said.

The rally concluded with a march to the U.S. Mission to the UN on 1st Avenue between 44th and 45th Streets. Keith Wyton with Peace Train Canada joined the rally and march to tell the Canadian Government to support the Treaty.

“The majority of Canadians support the treaty, but Canada is, as many other nations under the nuclear umbrella, and they’ve been basically focusing their defense and their foreign policy with NATO, which is a more militaristic approach,” Wyton said. “Our goal here is to tell the rest of the world that Canadians support the TPNW and to give a message to our Government that we’re down here because you’re not.”

Maylene Hughes, a grassroots organizing and policy coordinator for the nuclear threats program at Physicians for Social Responsibility Los Angeles, told amNewYork Metro it was imperative to educate the public about the danger of nuclear weapons. Hughes pointed out that the Doomsday Clock- a symbol representing the estimated likelihood of a human-made global catastrophe- was at 89 seconds.

“That’s the closest [the clock] been since the beginning of nuclear weapons,” Hughes said. “So it’s very startling. It’s very frightening, and we need to put nuclear weapons back in the media, back in the forefront.”