BY BILL WEINBERG | Adam Purple, my late estranged eccentric uncle. Did you know that I invoke your name and works every week?

For the past three years that I’ve been doing walking tours on the radical history of Alphabet City for the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space (MoRUS), I’ve stopped every Sunday in La Plaza Cultural community garden on E. Ninth St., told tourists and students and travelers about the successful struggle to save it from the bulldozers in the late ’80s. Then I sit them down in the garden’s gazebo and tell them that the struggle for La Plaza was immediately preceded by one for another impressive garden, south of Alphabet City, in the older part of the Lower East Side — and we lost that one. The rap goes something like this…

Back in the ’80s, the city government was using a divide-and-conquer strategy to break up the community gardening movement. They foresaw that the Lower East Side was going to be “redeveloped,” but all this land that had fallen outside of bureaucratic control — abandoned by the city and taken over by guerilla gardeners. Getting this land back under control was a form of counterinsurgency.

But back then, you couldn’t just take over a community garden to build a luxury development —for two reasons. First, the Lower East Side was still a “bad neighborhood” and the yuppies didn’t want to come here yet. And there was still enough working-class power in the neighborhood — a local political machine linked to the left wing of the Democratic Party — that they couldn’t get away with it. Later, in the ’90s, it became possible to bulldoze a garden for “market-rate” housing. But back in those early days it wasn’t.

So the city used a divide-and-conquer strategy… They’d say they needed the “empty lot” (because these vibrant gardens had no bureaucratic existence) for a public low-income housing project. This was an attempt to play the housing advocates off against the gardeners. There was a lot of overlap between the two groups — some housing advocates were also gardeners — but this was a means of driving a wedge between them. And there was one locally famous case where it worked…Adam Purple’s Garden of Eden, on Eldridge St.

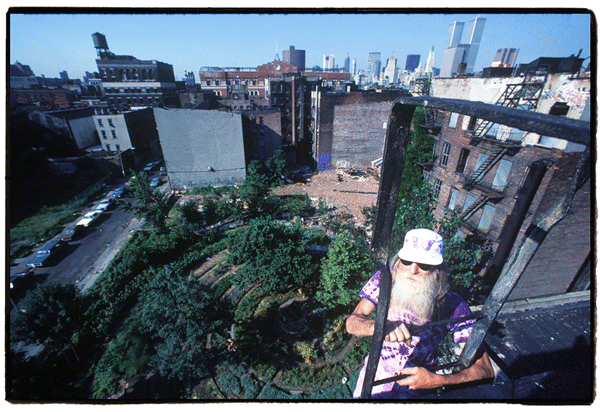

Adam Purple was an old hippie who was the last guy living in one of the last tenements left standing on the block. He’d been there since the early ’70s. The landlord had abandoned the building, all the other tenants had moved out, and he was squatting all alone, with no heat or electricity. Most of the rest of the block was a big vacant lot. And he started turning that expanse of blighted waste into a garden.

In the middle was a perfect Tao symbol made of flowers, beside a Chinese empress tree that apparently sprouted there of its own accord. Emanating out from the Tao symbol were concentric rings — one growing corn, another growing vegetables, another with fruit trees — until it covered the entire lot. And in his visionary or eccentric (depending on your point of view) ambition, Adam foresaw that it would continue to expand indefinitely — to other vacant lots around the neighborhood, and then throughout the city, breaking down the grid pattern and replacing it with a circular one more in tune with the Earth.

Adam looked the part. He had a long white beard and dressed in head-to-toe tie-dyed purple (including floppy hat) and wore purple reflecting sunglasses. He had a bicycle that he rigged with a wheelbarrow in the back, and he’d bike up to Central Park, fill the barrow with manure from the horse trails, and bike it back down to the Lower East Side to fertilize his garden. And that blitzed site, thusly nurtured, put out. He was growing food that he lived on and shared with his neighbors.

Then, in 1985, the city announced plans for a housing project on that site. The community was divided. Some people rallied around Adam’s garden; some rallied around the housing project. There was litigation. And in the end, the city bulldozers came in and destroyed it — in the dead of winter, in January 1986, when the flowers weren’t in bloom, and it was hard to mobilize people to the streets.

The following year, the city tried to do the same thing at La Plaza Cultural. That time, the community organized, fought back, and won. La Plaza still thrives today. But the loss of the Garden of Eden was a blow that set a precedent for the wave of garden destruction in the late ’90s and early ’00s.

I got to know Adam in ’85 when I was a young activist, amid the struggle to save his garden. His briefly published underground newspaper, the Inner City Light, was one of the first places I read about anarchism (some political theory amid Adam’s idiosyncratic, psychedelic wordplay). I even took acid in the garden one night.

Adam called his creation an eARThWORK —since it was both an earthwork and an artwork. In addition to horse manure, Adam used his own s— for fertilizer — “night soil.” He maintained that his strict vegetarian diet made his own excrement no more foul or hazardous than horse droppings. In one of his many alter-egos, Adam called himself Gen. Zen of the Intergalactic Psychic Police of Uranus. This was another pun. For Adam, we had to start thinking about how to integrate into the environment the stuff that comes out of your anus, and stop dumping it in the sea. “You don’t piss in your bathtub, do you?” he posed rhetorically.

Adam called the destruction of the garden a “political hit,” with complicity going all the way up to the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. And while I’m not sure about conscious federal designs, I think he was right. The tip-off is that there were plenty of vacant lots (I mean really vacant ones, without gardens) right in the immediate area. The bureaucracy clearly chose that one in order to wipe out Adam’s anarchistic experiment.

But there was also a depressing racial undertone to the struggle over the garden. Most (not all) of Adam’s supporters were from the white hippie, punker and squatter element in the neighborhood. Most (not all) of those rallying around the housing project were the older Puerto Rican and Dominican residents. One of the most aggressive boosters of the project (and opponent of the garden) was Margarita Lopez, then head of the Lower East Side Joint Planning Council. This was a body that coordinated low-income housing nonprofits (derided as “poverty pimps” by us anarchists) with the city bureaucracy, a pillar of the local machine.

Advocates of the housing project baited Adam as a loner, and said his productive artwork wasn’t really a community garden. And while he did share his produce and had some volunteers helping him out, it was very much his vision. (Earlier, before my time, there had been an Eve Purple — don’t know where she is now — and a coterie of young Purple People who looked to the couple as gurus.)

The housing project is there today, with the antiseptic name of Lower East Side Infill 1. It is more human-scale than many such projects around the city, but numbingly sterile, and (of course) bristling with security cameras. It is the cultural antithesis of Adam’s intricate spiral garden, which was a living embodiment of the ethic of “building a new society in the vacant lots of the old.”

In addition to his unswerving vegetarianism, Adam scrupulously refused to even set foot in an automobile. He would have no part of the petrochemical system at all. And even as a bicyclist, he always rode against the traffic, as a kind of statement. (He also said it was safer.) As far as I know, he never got ticketed for it.

For me, Adam was making a real statement about human survival in the industrial age. (He called his extensive archive of journalism about the garden and his own esoteric writings the Species Survival Library — and foremost among the species he meant was our own.) When I began writing about him for the (now-defunct) East Village weekly Downtown, where I did a column on city environmental issues, I made the point that his intransigent personal stance conveyed a needed sense of urgency. Technocrats at the big enviro groups were putting out white papers on the impacts of burning fossil fuels and dumping sewage at sea — while continuing, day after day, to drive cars and s— in toilets.

Adam continued to hang on in his old building facing Forsyth St. where he’d lived for nearly 30 years (most of that time squatting, although he considered himself a legal tenant), until finally the city evicted him to build housing for the deaf on the site around 1999. He did get a payout from the city government, in recognition of his legal tenancy. He left the city for a while, but returned — drifting, on the edge of society.

After 9/11, a group calling itself the New York Psychogeographical Association issued a statement calling for Adam to be named official Ground Zero gardener — and for a new Garden of Eden to rise at the site instead of skyscrapers. I took up this call, and had an opinion piece pushing the proposal in Newsday in 2002. I put Adam on WBAI radio, where I was then a producer, to plug the idea. Of course, I knew it was completely “unrealistic,” but I felt it was important to propagate, as a critique of the Cult of Giganticism and a reminder that other development models are possible.

And then in 2005, I made my faux pas that I don’t think Adam ever really forgave me for.

Starting with the previous year’s Republican National Convention protests, the N.Y.P.D. had launched a big crackdown on the Critical Mass bicycle rides. We took up the slogan “Still We Ride” to express our determination to be recognized as having a right to the road. And weekly public rallies in support of Critical Mass were held at Union Square, under the name “Still We Speak.” Political figures who came out to support us included fighting attorney Norman Siegel, Reverend Al Sharpton — and Margarita Lopez, by then city councilmember for the Lower East Side. So when I heard they’d invited Adam to speak at one of the rallies, I had a slight foreboding of trouble.

When I got up to Union Square that afternoon, Adam (no longer wearing purple, since the destruction of his garden) was waiting alongside the stage, looking dejected. I wish I had picked up on that, but I didn’t. I thought Margarita was going to be there, too (she wasn’t, it turned out), since she’d spoken at the previous week’s rally. And I knew Adam had never forgiven her. Half in jest, I said, “Adam, do me a favor — when you speak, don’t diss Margartia.”

I didn’t anticipate his response. Without a word, he hopped on his bike and pedaled out of there, headed back to the Lower East Side.

He never spoke to me again after that. A few days later, I sought him out at the (now gone) Tres Aztecas Mexican restaurant on Allen St. The folks there had taken him in, feeding him rice and beans for his help around the kitchen. I apologized, told him that what I’d said had been “very un-anarchistic.” At this he nodded vigorously, but he wouldn’t say a word or look at me. Adding to my chagrin, the next week’s Villager had a photo of Lopez with her arm around Mayor Mike Bloomberg (author of the Critical Mass crackdown) as they schmoozed over the East River Park redevelopment plan. Later, she would endorse Bloomberg for re-election, then get a post in his administration. I came to bitterly regret my words.

In the decade after that, I’d wave at Adam when we passed each other on our bicycles, and he’d wave back. But never a word — not even to return my “hello.”

After MoRUS opened (on the ground floor of C Squat, on Avenue C), I saw my chance to reconcile with Adam. At the big inaugural party for the museum in December 2012, Adam was brought in to speak. By this time, he was crashing at the Williamsburg space of the urban environmental group Time’s Up, whose leadership overlaps with that of the MoRUS. I saw my opportunity to show Adam some love and respect, and maybe atone for my old error. I got there just as he was supposed to speak, having figured that would be well in advance — Lower East Side activist events typically run behind schedule. Wouldn’t you know this was the one time they were actually ahead of schedule? I arrived minutes after Adam had left.

I never got another chance. On Sept. 14 , Adam died at the age of 84 — apparently of a heart attack while bicycling over the Williamsburg Bridge. I think the fact he died on his bicycle is appropriate.

On Sat., Sept. 26, there was a memorial for Adam, with artifacts of his life and works on display at MoRUS and testimonials around the corner in La Plaza Cultural. It was announced that he’d been given a chemical-free “green burial,” at a place that provides such services in Upstate’s Tompkins County. It is again fitting that Adam was himself composted. I wish he could have heard me say in life what I said of him at the memorial — that he was one of the few true revolutionaries that I have known, and that I loved and respected the hell out of him.

Adam Purple, you tough, stubborn, infinitely idealistic old coot. You sure were hardcore.