BY STEPHANIE BUHMANN | Marking its first installment in the museum’s new home in the Meatpacking District, the Whitney Biennial is as comprehensive as it is eclectic. Curated by Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, both in their mid-30s, it reflects the result of several months of research and studio visits. There are 63 participants in total and many more works on display, spanning two entire floors and reaching into several others. Although the Whitney Biennials have always aimed to present a cross-section of current American art — and trends — this year’s 78th edition certainly counts among its darkest.

You will find little art about art, or purely conceptual positions. We live in a world filled with explosive issues. Coming at a time rife with racial tensions, economic inequities, and extremist politics, this Biennial was not conceived to divert our gaze or offer any sense of escapism. Instead, it aims to address vital issues at hand and, as a result, serves as a stunning reminder that visual art can count among the most poignant reflections of our era’s pulse. In fact, art thrives when times are challenging.

A good way to tour the vast assemblage of objects, installations, and thoughts is from the top down. As soon as visitors step off the elevator on the sixth floor, they will be facing Henry Taylor’s almost mural-sized canvas “Ancestors of Genghis Khan with Black Man on Horse” (2015-2017). Painting large comfortably, Los Angeles-based Taylor is known for his innovative exploration of portraiture. He is an avid chronicler of the world he observes, primarily his immediate surroundings. His figures, set against simplified backgrounds, point at increasingly visible racial tensions, especially between law enforcement and communities they serve. They are both poetic and to the point. Nearby, several more of Taylor’s works can be viewed, counting among the best this Biennial has to offer.

Turning 180 degrees, one will find three small sculptural works by New Mexico-based artist Puppies Puppies. Upon closer inspection, one can recognize each as a gun trigger, albeit stripped of most of its context. These works belong to the artist’s “Triggers” series, which focuses on the mechanism that prompts a gun’s firing sequence. Here, each piece marks the leftover remains of a Glock 22 destroyed at the artist’s request. While drawing attention to the ongoing misery of gun violence in America, these works also come from a personal place. Wall text informs the viewer that the artist’s mother was held at gunpoint in a school parking lot when he was 11 years old.

Throughout the museum, sculptures by Jessi Reaves can be discovered. Merging found objects such as baskets, electrical wiring, and a vinyl purse with natural materials like driftwood, she creates unusual concoctions that hint at the former functionality of their ingredients. Her sculptures range from complex to rather simplistic. An example of the latter is “Herman’s Dress” (2017), for which she sheathed an Eames Herman Miller sofa in a translucent pink silk slipcover. The modernist piece of furniture takes on an unexpected disguise, as well as an air of both eroticism and kitsch.

Also drawing on found objects, yet with an eye on abstraction, Kaari Upson turns stained paper towel rolls and upholstered furniture into lush sculptures. In the past, she has used a weathered sectional sofa that she left exposed in the driveway behind her Los Angeles studio for a year. It is through the reorientation of such objects and the painting of their soft surfaces that Upson succeeds in obscuring her source. In fact, her pigment-covered sculptures faintly evoke the work of some artists not exhibited here, such as the Glasgow-based Karla Black and the American John Chamberlain. Chamberlain’s sculptures, made of compressed automobile parts, seem like hard-edged and highly saturated counterparts to Upson’s gentler biomorphic forms. Like Black, Upson finds a way to bestow an air of the extraordinary on the ordinary.

One of the largest installations by a single artist — or in this case, artist collective — comes in the form of KAYA’s “Serene” (2017). The sprawling display is made of 13 large works, both installed on walls and hanging freely from the ceiling. It is a number sparked by the artists’ muse, collaborator, and name-giver, Kaya Serene, a friend’s daughter, who was 13 when the collective started working together in 2010. As KAYA, Kerstin Brätsch and Debo Eilers explore the intersection among sculpture, painting, installation, and performance. Involving an array of components such as hardware, synthetic leather, translucent supports, suede, tiles, and cast resin fragments, the works are as faceted as they are theatrical.

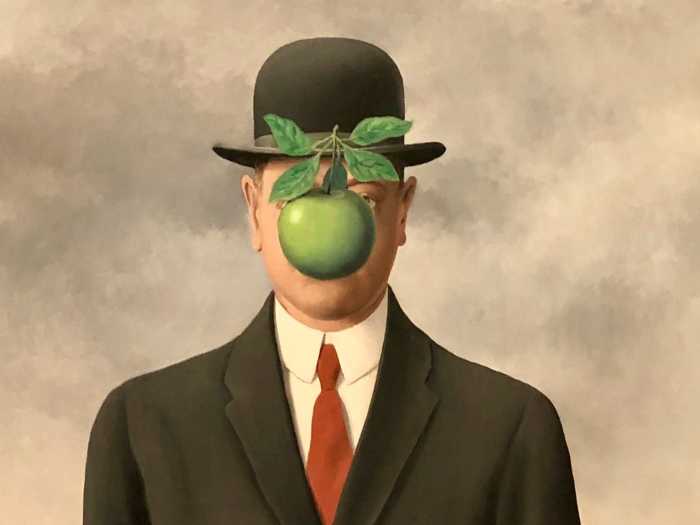

While there are plenty of paintings to discover, most of them are figurative and some even illustrative in nature. Among these are a group of six un-stretched canvases by the formidable American artist Jo Baer, who has been based in Amsterdam for years. Born in 1929, Baer might be looking back at more than six decades of painting, and yet her work couldn’t look timelier. Begun in 2009, her series “In the Land of the Giants” is rooted in her research of the Hurlstone (Holed Stone), a prehistoric megalith in County Louth, Ireland. Baer’s imagery, which spans from human and animal figures to references to paintings, was sourced from the Internet and composed with the help of digital media. The results are strange amalgams of visual information that confuse our traditional perception of space and time. Despite their far-reaching content, Baer’s paintings are far from cluttered; they are sparse, soft in palette, and elegantly conceived.

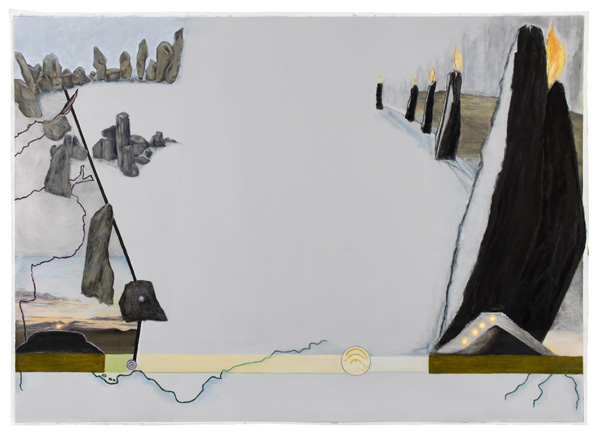

Other examples of resonant paintings are five large abstract canvases by Carrie Moyer and six compositions by Shara Hughes, highlights in an otherwise disjointed fifth floor. Moyer’s compositions are abstract — and since the early 2000s, they have involved the use of small collages as a starting point. Meanwhile, Hughes’ exuberant landscapes stem from the imagination. In contrast to Moyer’s larger paintings, which envelop the viewer, Hughes’ works are of a medium scale and appear as windows or even portals into otherworldly landscapes. Their almost hallucinatory quality evokes the late watercolor landscapes of Charles Burchfield, which the Whitney featured in its old Breuer building in 2010. Hughes frequently begins a composition by altering the canvas’ surface by covering it in a glue-like substance or spray-painting its back. These first steps serve as a self-imposed challenge, to which the artist then has to respond. Overall, Hughes’ scenes are far from harmonious. Underneath these saturated colors remains the suggestion of something unhinged, if not post-apocalyptic.

Hughes’ landscapes in particular make for an interesting segue to “A Very Long Line” (2016), a four-channel digital video installation by Postcommodity. Filling an entire self-contained space, it focuses on the border between the US and Mexico, an emotionally and politically charged site for years, but even more so since the 2016 election. Filmed from a car window, the footage is projected along with an out-of-sync audio component. The result succeeds in disorienting the viewer, reflecting its premise that the border, which was predated by important indigenous trade and migration routes, is not fully known or truly understood.

One of the most brutal experiences is offered by Jordan Wolfson’s “Real Violence” (2017). Employing virtual reality headsets, his high-definition video lasts no more than two and a half minutes, yet one will not leave quite the same. During that brief time period, we witness an act of unexplained and incredible violence as it unfolds on a sunny day in a Western city. A recording of Chanukah blessings, city traffic, and violence form the tangled soundtrack to the visuals. Due to the virtual reality headset, one can easily turn away from the scene and focus on trees or disengaged passersby instead. However, one can never escape the sound, which is as prominent as if one were to stand right in the middle of the event. In Wolfson’s film, we might be able to turn our back on the deadly assault of another human being, but we aren’t permitted to stop listening to it.

It is a sickening experience, which leaves a lingering feeling that will get triggered — though less overtly — several more times. On the fifth floor, the intimate Dana Schutz painting “Open Casket” (2016) depicts Emmett Till in his coffin (her monumental work “Elevator” from 2017 faces the fifth-floor elevator). In 1955, the 14-year-old African American boy was accused of having flirted with a white woman and beaten and shot to death. When Till’s mother decided to have an open casket at his funeral, traces of the brutal assault were made visible to all. Schutz’s work captures Till in his casket, reinterpreting his mutilations through thick layers of paint and a deep gash. This is hardly a graphic depiction of the subject, and yet Schutz succeeds in finding a form for a layered feeling. Even without reading the title and wall text, we sense there is something completely wrong, dark, and senseless before us.

The abstract, geometric enamels by Ulrike Müller, focused on feminist and genderqueer concerns, serve as a reprieve. A member of the feminist genderqueer collective LTTR, she has used text, sculpture, weaving, video, performance, painting, and drawing in her work. Müller continuously explores the relationship between abstraction and the body. Employing geometrical figures and color surfaces, the compositions on display here exude an erotic and sexual quality.

ARTIST’S COLLECTION, COURTESY OF COMPANY GALLERY, NEW YORK/ PHOTO BY MATTHEW CARASELLA

Certainly, the Biennial is filled with many more works to explore. Raúl De Nieves’ impressive site-specific installation on the fifth floor and John Divola’s photography series are among them. De Nieves covered six floor-to-ceiling windows with 18 “stained glass” panels, which he created with paper, wood, tape, beads, and acetate sheets. Divola captured discarded student paintings on the walls of abandoned buildings in Southern California.

This most elaborate installment of the Whitney Biennial is impossible to take in during a single visit. And, the Whitney has given the online presentation much thought, as well, its website, perhaps for the first time, serving as a valuable resource for those who have seen the works in person and those who have not.

This Biennial provides less of an overview of what is currently being made in American art than a compilation of excerpts of voices that deserve to be heard. This year there will be a less lively debate about the exhibition’s overall quality — usually a given as much anticipated as the event itself. Who will argue against a show that gives a forum to valuable criticisms? But if you are looking for a feel-good distraction in a time of anguish, contain yourself to the permanent collection on the Whitney’s upper floors.

2017 WHITNEY BIENNIAL | Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort St., btwn. 10th Ave. & Washington St. | Through Jun.11 (sixth fl. exhibit to Jul. 16): Sun.-Mon., Wed.-Thu., 10:30 a.m.-6 p.m.;Fri.-Sat., 10:30 a.m.-10 p.m. | $22 at whitney.org; $25 at the door; $17/ $18 for students & seniors