By Lucas Mann

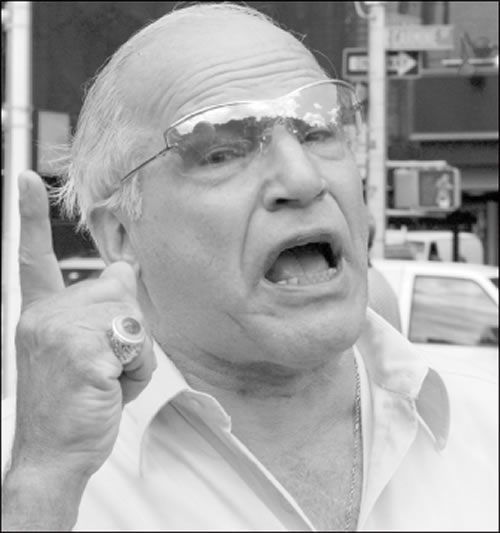

Maybe you’ve seen him. The Mayor of Spring St. Seventy-two years after he was born on this same block, Richie Gamba still does not seem in any hurry to leave. Everyone and everything else from the old neighborhood has left — most of the Italians, most of the Portuguese and nearly all of the rent control — but Richie remains to remind anybody, well, more like everybody, of the history of the neighborhood.

“We used to play stickball right there in the street,” he said, perched on his customary folding chair in front of the Hair Box barber shop on Spring, between Sixth Ave. and Sullivan St. Predating Richie on Spring St., the Hair Box is more than 100 years old, still with the classic red-and-white pole out front and straight-razor shaves. Richie says it’s the oldest barbershop in Manhattan and, for him, it’s the closest thing he has to a clubhouse. There used to be a lot more of that neighborhood feeling in the old days.

“When the horse and wagons would come by with the watermelons in the summer, we’d jump on and go for a ride,” he said with a smile.

Most of Richie’s stories seem impossible to place on a busy afternoon in Soho, with young people wearing vintage sunglasses, walking small dogs and toting Apple Store shopping bags. When Richie talked about going crabbing and fishing along the Hudson River, it was difficult not to cringe.

“It used to be a strong neighborhood,” Richie said, balling his hands into fists. “We used to fight the Irish. We had to fight our way up around here. I used to box, you know, Police Athletic League, $30 a fight. I hung around Rocky Graziano. We went to the all the clubs — I was 17, 18.”

As we talked, an unmarked black van drove up and parked behind Richie. He gave a casual glance and then said, “You want some salmon? Good salmon. Free.”

This was too much. I froze, looked around, and mumbled that I had already eaten. A young man came up and gave Richie a plastic bag — inside were two salmon fillets, some bread and an uneaten birthday cake that was still good. Richie looked at my face and chuckled.

“God’s Love We Deliver,” he said, pointing at the young man who had come out of the van, which brings meals to the chronically ill. “This is a good guy — Junior. This guy works 40, 50 hours a week and gets limited pay. Some of these people around here, they make, what, $600,000? They don’t care about anyone.”

We had hit the focal point of Richie’s conversations. He misses a time when the neighborhood was — according to his memory — peaceful, simple, working class. He takes it upon himself to try to take care of some of the old women who have not fled the neighborhood, and to keep order. He gives the God’s Love We Deliver leftovers to the old women who don’t want to leave their apartments on hot days. He has also developed a relationship with the man that owns the candy store next to the barbershop and, when the kids used to steal from him after school, he put an end to it.

“There’s a couple of people from the old neighborhood who are still around,” he said. “We sit and reminisce. But we old types, we’re secretive. We’re used to protecting each other. In the ’80s, most of the Italians started moving out. Now they sell our old places for 275 grand.”

Richie misses the camaraderie as much as he misses all of the old traditions that used to happen in the neighborhood.

“I want the Feast of St. Anthony’s back here,” he said. “Barbecuing in the street, dancing, getting the fire hydrants going. They took it away because all the new neighbors had to go to their jobs the next day. ‘The noise,’ they said. They thought the mob ran it. What mob? The only mob I see is the one pushing you in the subway.”

Strangely, while he bemoans the change of his neighborhood and the stereotypes that new residents may have about the old days, Richie’s notoriety, as well as part of his income, comes from what a unique personality he is in the new Soho. Passerby after passerby stops by the folding chair to say, “Hey Richie.” He pets their dogs, makes jokes and sends them away happy. And those are just the nonfamous ones.

Twelve years ago, a young woman walked by the chair and told Richie that she liked his look. He responded, “I like your look, too.” Soon, Richie was in the Screen Actors Guild. The window of the Hair Box is cluttered with photos of Richie from all kinds of productions — Richie with the cast of “The Sopranos,” Richie with his arm around Mariah Carey on the set of “Glitter,” Richie filming a scene from “Analyze This.” Richie Gamba is now called on to play the old-school Italian guy that has disappeared from his neighborhood. In an odd way, he has come full circle.

Sure, he likes the attention, and there’s no way he’ll ever leave his home turf, yet Richie refuses to let the change of his neighborhood go uncommented upon.

A small Portuguese woman, another veteran of the neighborhood, joined us on the street, commiserating with Richie about the way things have changed. She remembered days of old factory buildings and lots of families.

“Now it’s like a hotel around here,” she concluded.

Richie glanced both ways, up and down the block.

“Heartbreak hotel,” he said.