Before Central Park was the landscaped, green jewel of New York City, it was a wild stretch of land, full of marshes and rocks.

And when it came time to design the new park, no detail was too small.

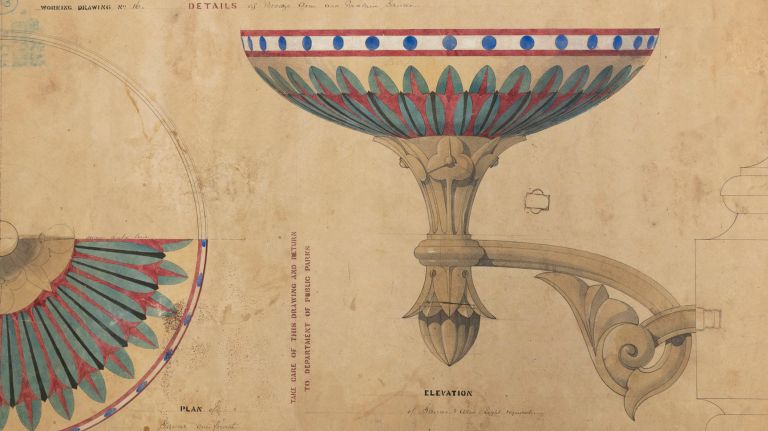

Elaborate and colorful drawings in the city’s Municipal Archives provide an interesting window into those plans which included intricate, Victorian-era birdcages, stately horse troughs and sketches of a grand Bethesda Terrace.

A new book, “The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure,” includes more than 1,000 of those drawings with an explanation of the creative process.

“They are so fascinating and the park is so integral to the city,” said author Cynthia Brenwall, a conservator, who treated and digitized 1,800 Central Park drawings that are part of the larger city parks collection at the Municipal Archives.

“You can see these drawings, go to the park and they are still there,” she said. “Maybe they are not being used for the original purpose but many are there.”

For example, the birdcages are gone but their bases are now used as planters.

As the population of the city grew in the 19th century, lawmakers and civic leaders wanted a lush, spacious park where anyone — rich or poor — could go to get away from hectic urban life.

“It was imagined as a place where regular people could congregate and get out of the city and enjoy a natural environment,” said Pauline Toole, commissioner for the city Department of Records and Information Services which maintains the Municipal Archives. “This was the first time anything like that had been attempted in the country as a public park.”

Several sites were considered before settling on the large swath of land from 59th to 106th Street between Fifth and Eighth avenues. The park was later extended to 110th Street and now encompasses 843 acres.

But the transformation wouldn’t be easy. The unfriendly, marshy terrain had to be drained. And there were people living on the land, including Seneca Village, where a community of African-Americans had purchased property, built homes and churches.

Eminent domain was used to push them out and everyone else living in the park, including a smaller group of immigrants from Ireland.

The process of selecting someone to design the new park was full of intrigue. In 1855, engineer Egbert Viele completed a masterful topographical survey and hoped to be the designer of the park. But architect Calvert Vaux and designer Frederick Law Olmsted won the competition with their Greensward Plan in 1858. Even though that plan is acclaimed as a hallmark in landscape architecture, some grumbled it was their close political ties that sealed the deal.

The Greensward Plan followed the English naturalistic style featuring lakes, hills and meadows with more formal pieces of architecture like Bethesda Terrace and its majestic fountain.

Vaux worked with fellow architect Jacob Wrey Mould on the park’s bridges, created to keep walkways from heavier trafficked paths.

The east-west transverses were placed below park level and hidden behind dense greenery to maintain the pastoral environment.

“You were to immediately have the sensation that you were no longer in New York City,” said Assistant Commissioner Kenneth Cobb. “I think they achieved that to a remarkable degree. Even to this day, you go into that park and you suddenly realize you’ve left the city.”

Brenwell said she was riveted by the engineering drawings and infrastructure plans.

“They had to excavate land that was so rugged,” she said. “I never knew I would be so fascinated by drainage.”

Topsoil had to be imported into the park along with trees and plants.

The book allows the archives to show off some of its treasures and shine a light on the work of Vaux and Mould.

“Olmsted gets most of the credit but Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould were just were phenomenal,” Toole said.

Some of the sketches illustrate plans that never came to fruition, such as construction of a museum dedicated to dinosaurs inside the park.

The drawings themselves have an interesting history. Some were found in a park facility in lower Manhattan, while others had somehow made their way into private hands. Over time, they were all brought to the Municipal Archives.

“We look at them now and you say ‘This is a work of art,’ no question,” Cobb said. ‘But that was not their original purpose. They were drawn so that the iron monger, the carpenter, the stone mason would know exactly how to build whatever the subject was … so these are working drawings that are now works of art.”