By David Stanke

The commission expressed broad agreement that there will be another attack and it will probably affect New York City, perhaps worse than 9/11. Against this backdrop, the commission did generate one very obvious finding. The city and the country are living in a state of denial thinly concealed by rhetoric and impassioned speeches. We have an enemy who is “versatile, smart, entrepreneurial.” Our response to this enemy lacks these very qualities, reflecting instead inflexibility, a blind mentality, and a bureaucratic government culture.

Any assessment of the 9/11 response has to begin with one clear fact. Thousands of emergency responders raced to the site and gave everything they had to save lives. There is no question about the bravery of the individuals of the N.Y.P.D., Port Authority Police Dept., and F.D.N.Y. The 9/11 Commission needed to get beyond this to determine if the decisions, communication and controls effectively channeled this these efforts. When 3,000 people die, it is valid and necessary to ask if there was any way that the casualties could have been reduced, even if only by 10 lives.

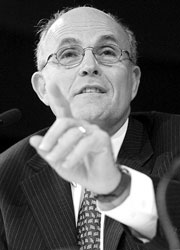

When questioning Giuliani, the commissioners heaped praise on Rudy and N.Y.C., consuming time that could have been used for further questioning. Three years after the attack, with warnings of another attack this summer, we don’t need to hear any more praise. Fred Fielding thanked former Mayor Giuliani for being a “symbol of resiliency to New York and all of America.” Symbols may help us deal with the pain of loss, but they don’t stop the next loss. The point of this commission is a safer future. Instead they wasted our time with speeches of sympathy and admiration. To imply that asking tough questions is an insult to the deceased heroes is a betrayal of the people who elected him.

To put this in context, consider Mr. Giuliani’s current job. He formed a consulting company, Giuliani Partners, with many of his former deputies. The Giuliani I heard had no innovative suggestions or useful insight into city security procedures or organizations as a result of the worst domestic tragedy in our history.

As a consultant, I understand that the most important factor for a successful project is the willingness of the client to honestly and directly address shortcomings. The commission exposed a city leadership that lacks introspection and is resistant to change.

Strong leaders would have come to the commission with explicit programs and projects to strengthen our response to any emergency situation. That opportunity is gone. Now we have to depend on the commission to generate recommendations. The following five items provide a starting point.

First, New York needs more than its share of federal funds to fight terrorism. Mayor Bloomberg hit the first issue on the head. Defense requires dollars, and New York is the front line of the war.

Second, we need better ways to communicate with private corporations and individuals in the disaster. As survivors from within the W.T.C. tell us, the public is the first and sometimes the only responder, at the scene of the attack. The majority of injured and “at risk” people on 9/11 were unreachable by emergency personnel. From these conditions, we have stories of self-sacrifice, bravery, and intelligence. We also know that the wrong or insufficient information can have devastating affects. If the next attack is as certain as everyone seems to think, the city should stop treating citizens like sheep and start training us to respond.

The head of security for Morgan Stanley understood this, initiating his own emergency preparedness procedures that were remarkably successful at protecting employees. Residents of Battery Park City who witnessed the attacks have recognized this need. The Battery Park City Neighborhood Association and local residents including Rosalie Joseph, Anthony Notaro, and Sid Baumgarten have initiated a certified emergency response team (CERT) to train building management and interested individuals. In these cases, people have gone beyond government procedures to increase their own safety.

Third, the city needs to improve methods of collecting accurate information and quickly getting it to people under attack. If the Port Authority had known that multiple planes had been hijacked after the first plane hit, they might have called for an emergency evacuation of both towers. Hundreds of lives could have been saved. If 911 operators had known that the buildings were at risk of collapse, they could have told people to search for an exit immediately.

Fourth, we need better accountability for decisions made regarding emergency preparedness. The location of the Office of Emergency Management command center at the destroyed W.T.C. 7 was so obviously bad that no comment was necessary. But while Giuliani spent 9/11 looking for an alternative command post, he did not even mention it as a mistake. The standard communication technology in use by police and fire departments is also clearly deficient and the individuals using the equipment didn’t trust it.

Fifth, the Police and Fire Departments must set aside their rivalries and realize that they are on the same team. An innovative management consultant might suggest programs to break the cultural divide. The city recently released guidelines for establishing the chain of command at emergency scenes, but the standards seem to establish the conditions for regular debates between police and fire. The situation is complex and difficult, but police officers, fire responders’ and citizens’ lives are on the line.

If you are city management, you can take a version of this list and start moving. Alternatively, you can take consultant Giuliani’s advice that we couldn’t have responded differently and do nothing. The motivation for city leaders to take strong action was lost when the commission decided not to shake the boat and not to focus on the elected leaders who were and are responsible for safeguarding this city. In response to a vocal critic at the 9/11 hearings, Thomas Kean, the commission’s chairperson, said, “If you want to be disruptive, you will be removed from this room!” It would appear that he gave this same directive to the members of the commission before they started to hear testimony.

David Stanke is co-president of BPC United, a group of Downtown residents, and can be reached at bpcunited@ebond.com.