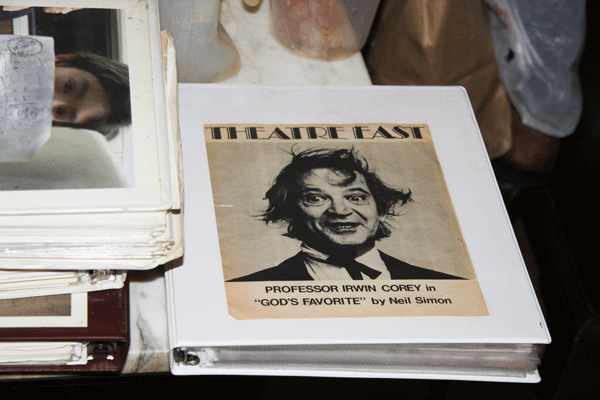

BY ALBERT AMATEAU | Professor Irwin Corey, in his frock coat, string tie and wild hair, emerged again last month to deliver another lecture.

Corey’s appearance, for 20 minutes at the April 24 showing of Jordan Stone’s documentary “Irwin & Fran” at the East Village’s Anthology Film Archives, brought the house down.

Laughter has followed Corey for at least 80 years in a career of stand-up comedy, political satire and as an actor on stage, film and television.

At the age of 99 (he was born in July 1914), Corey shows few indications of slowing down.

He went to the film showing with his son, Richard, and Jim Drougas, a friend and the owner of Unoppressive Non-Imperialist Bargain Books, on Carmine St.

“He climbed the three flights of stairs to the auditorium,” Drougas said, “and after the film he got up holding his walker in one hand and the microphone in the other and had everyone in stitches.”

“An audience always gives him a surge of energy,” his son said later.

The film, about Corey and his wife of 71 years, who died in 2011, features the comedian Dick Gregory and is narrated by Susan Sarandon.

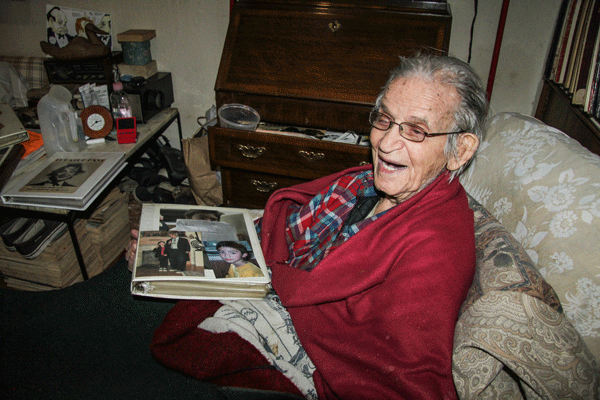

Last Sunday, Corey entertained Drougas and two visitors from The Villager at his home in East Midtown where the conversation turned to show business, show reviews and politics, the latter a frequent topic with Corey, who embraces the radical left with both arms.

“Jim, show them the picture with Richard and Fidel Castro,” he called to Drougas. “You know, Obama has Alzheimer’s,” he told his guests with a straight face. “He forgot all the campaign promises he made.”

Corey was blacklisted in the 1950s.

“When I tried to join the Communist Party, they wouldn’t have me because they said I was an anarchist,” he said. “I think I am.”

A middling review in Variety of “Irwin & Fran” didn’t seem to trouble Corey.

![Closing in on 100, Professor Corey still cracking wise 3 A framed photo of Corey embracing Fidel Castro in 1993. Castro signed the piece of paper that goes with it, “For Irwind [sic] Corey, with admiration, gratitude and affection.”](https://www.amny.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/corey-castro.png)

Tynan, however, had written that Corey was “a cultured clown, a parody of literacy, a travesty of all that we hold dear and one of the funniest grotesques in America.”

Corey took on the comedy persona of “The World’s Foremost Authority” early in his stand-up career. The act opens with him franticly searching his pockets for notes, losing them again and opening with the word, “However… .”

“I was playing the Village Vanguard in 1942 when Richard Dyer-Bennet [a renowned folk singer] introduced me as ‘professor’ because I was giving a lecture on Shakespeare that began with, ‘In the play, “Othello,” which we know as “Hamlet,”’” he recalled.

“The Vanguard paid me $40 a week — that was four times the average annual salary at the time, and they raised me to $60,” he said. Corey’s conversation, especially about politics, is full of statistics. How does he remember all those facts and figures?

“I make up what I don’t know,” he confessed.

Corey was born in Brooklyn, one of six brothers whose parents had to give them up periodically to the Hebrew Orphan Society.

“In 1933 I went to California and got into a school, Belmont High in Hollywood,” he said, recalling that he had a part in the school production of “Seven Keys to Baldpate,” a popular play written by George M. Cohan 20 years earlier.

In 1934, the budding actor returned to New York. It was the beginning of the Great Depression, and Corey became involved in left-wing politics, show business auditions and boxing in the Golden Gloves as a featherweight — 112 pounds.

Corey said he doesn’t remember when he became aware of politics, but one of his many scrapbooks has an article dated 1927 about Sacco and Vanzetti, two anarchists executed for murder. They were a cause célèbre in the late 1920s; Corey was 13 at the time of their deaths.

Around 1938, Corey landed a minor part in a Borscht Circuit show, “Pots and Pans,” and his career began in earnest. He is proud of his role as the gravedigger in “Hamlet,” directed by Zoe Caldwell.

“I played another Shakespeare character, Christopher Sly [“Taming of the Shrew”], a drunken tinker who thought he was a lord,” he recalled.

Corey is satiric and skeptical about religion as well as politics.

“Yip Harburg — he wrote ‘Finian’s Rainbow’ — wrote a play called ‘Flahooley’ that I was in,” he recalled. “It was picketed by Catholics for being anti-religious but it ran for 44 performances.

“I played the Copacabana in 1947 or 1948. Joe E. Lewis [a comedian and singer of the time] refused to play on Yom Kippur, so he recommended me because he knew I didn’t give a kipper about any of that,” Corey recalled. He likes to say, “I’m a Jew but I’m not Jewish.”

In 1974 he bought the house in Sniffen Court, in the E. 30s, where he still lives. The duplex’s ground floor is full of memorabilia, including paintings by his son Richard. One of Corey’s grandsons, the son of his daughter Margaret, who died in 1997, looks after him.

“When I bought the house, the taxes were $3,000 a year. Now they’re $18,000,” he said. “That’s illegal. The Constitution says that Congress may levy taxes, not the city or state. If I live another 10 years, it will cost me $180,000 to live here.”

Corey is optimistic about his future.

“I saw on television,” he told his guests, “that a man in India was 200 years old. Another guy was 250 years old.”