A Manhattan judge has dealt an early blow to an effort by a group of fellow jurists to strike down New York’s judicial retirement mandate.

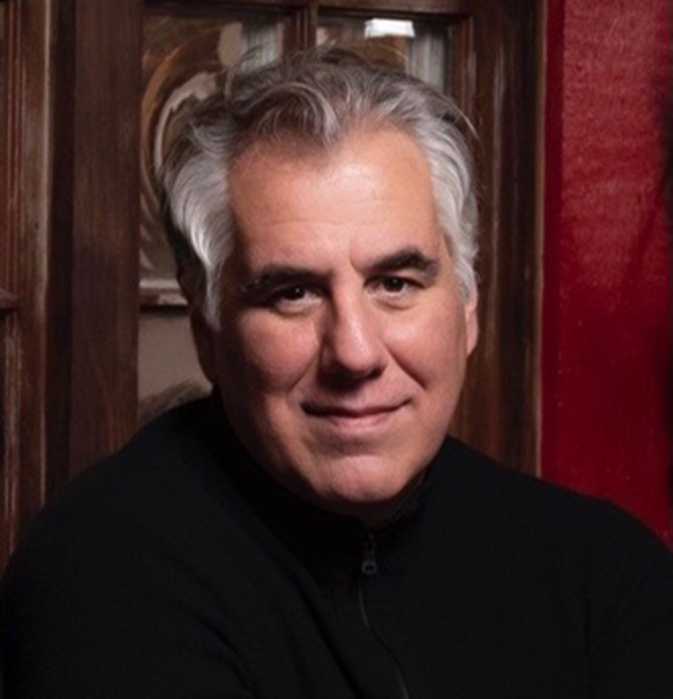

The plaintiffs — Appellate Division, Second Department Justice Robert Miller, Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice Richard Montelione and Staten Island Supreme Court Justice Orlando Marrazzo Jr. — allege in a lawsuit filed last month against the state and the Office of Court Administration that judicial age limits violate an equal rights amendment to the New York state constitution that voters approved last year with 62% of the vote.

Under the current retirement laws, Miller and Marrazzo, who both turned 76 years old during the current calendar year, must step down after Dec. 31. Meanwhile, judges who turn 70 years old — as Montelione did this year — must regularly prove their competency to do the work if they intend to stay on the bench.

In his ruling to deny the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction to bar the state court system from enforcing the retirement mandates, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Lyle Frank said that, for New York’s new equal rights amendment to apply to their case, the judges would need to show that the age limits “violate a civil right of theirs.”

The judges “have not shown, nor is the Court aware of, a civil right consisting of the ability to remain a judge,” Frank wrote.

The plaintiffs’ legal team, which include retired Appellate Division justices David Saxe and John Leventhal, said they are appealing Frank’s ruling to the Appellate Division, First Department.

David Scharff, a senior partner at Morrison Cohen, said in a statement to amNewYork Law that Frank “made a fundamental error in its constitutional interpretation of the problem presented” and “improperly narrowed the scope of the civil right being challenged by the State and OCA, age-related employment discrimination and at the same time ignored the legislative predicates in New York that have outlawed such age-related employment discrimination.”

A spokesperson for the New York Attorney General’s office, which is appearing for the state and the court system in the matter, declined to comment.

In their petition, Miller, Montelione and Marrazzo note that New York first set its judicial retirement age at 70 years old in 1869, when a male’s average life expectancy was 41 years old. It is now almost 79, according to their complaint.

While Frank ruled to dismiss the judges’ lawsuit, he clarified in his ruling that he is not dismissive of the idea that mandatory retirement ages for the judiciary should be reconsidered.

Observing that “there are serious public policy concerns with the current judicial mandatory retirement age scheme,” Frank noted that changing the law would require an amendment to the state constitution.

“The Court may be able to add its voice to those urging the New York legislature to reconsider the issue of mandatory judicial retirement ages, but that remains all it has the power to do,” Frank said.

The most recent effort to change the judicial age limit by constitutional amendment proved unsuccessful, even with the endorsement of then-Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman. In 2013, New York voters rejected a ballot measure to raise the retirement age to 80 by 58% of the vote.