By Lori Haught

Christopher Prince knew Downtown. He’d lived there much of his adult life. He helped the fight for freedom during the Revolution, and by his 70s he had seen the city grow into a thriving metropolis, although Greenwich Village was still considered the countryside.

In a journal, spanning from 1821 to 1825, Prince chronicles the Yellow Fever epidemic, church life, and living on Gold St. and Cherry St., at the sites where two 20th century housing complexes were later built, Southbridge Towers and Knickerbocker Village.

He talks about the streets we walk along today: John, Cherry, Front, Murray, Water, Pearl, Wall Sts., and Broadway.

Charles Prince, of Houston, Texas, brought the journal to the attention of the Downtown Express after finding the link to the online version of the journal when he was searching for answers in the life of his fifth great-uncle.

“Last year I only knew who my grandfather was,” Charles said of his recent delve into the Prince family genealogy. “It’s fascinating.”

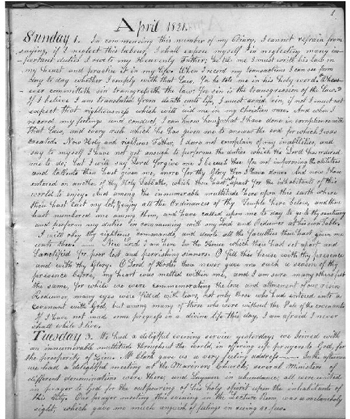

The journal, a plain brown leather-bound book with yellowed pages filled with beautiful cursive, is currently located at the Mystic Seaport Museum of America and the Sea in Connecticut’s “Ocean Corner.”

Born to Kimball and Deborah Fuller Prince in Kingston, Mass. in 1751, Christopher only received formal education until the age of 12 or 13, Charles said. He was married to Lucy Colfax, although there is no mention of her in this journal, and they had no children. Family was still a vital part of Christopher’s life, as he speaks of relations often. It was important to him to pass the family history down to his nieces and nephews.

Christopher described many daily aspects of his life in Downtown New York with great detail. Much of his activity centered around prayer and religious writings as well as receiving letters from his family. He took little time mentioning the more modern aspects of daily lives like shopping, bathing, and eating out.

George Thompson, New York University librarian and New York City history buff, said that was most likely because Christopher did not enjoy these amenities.

“If someone in the present day were to go back, what would strike them first is how much the city must have stunk,” Thompson said. “There was no running water in city. People either had a barrel to collect rain water or they got water from pumps on street corners.”

Thompson said this turned taking a bath into a major ordeal. He also said there was no garbage collection and most people threw their trash out on the streets where pigs could roam and find food. The streets would have been filled with animal feces, which to people today would have been repulsive, but it was everyday life to Christopher.

“Another thing that people would have been struck with is how quiet the city would be and also how dark,” Thompson said. There was no electric, or even gas lights in the early 1820’s so most people tried to avoid lighting their houses. “There were no car alarms, whistles, or sirens, but the people then didn’t think their city was quiet,” Thompson added. “[Letters to the editor] complained about the sound of horses hooves on paved roads. The perception of the city then was different than what our perception is now when thinking or reading about it.”

Without all the light pollution, it was easy to see amazing astrological events. Thompson said there are stories of people being able to see the Northern Lights from New York at that time. One of the first entries in the journal describes the solar eclipse of Aug. 28, 1821.

“Yesterday there was an Eclipse of the Sun, which filled the atmosphere with gloome, which chilled the body, and beclouded the mind,” Christopher said, going on to talk about bidding a visiting pastor goodbye and praying for an “afflicted” family.

First and foremost, he seemed to be a devoted Christian, although he did not mention the sect. In fact, that was his reasoning for keeping the diary.

“I shall expose myself in neglecting many important duties I owe to my Heavenly Father; he tels me I must write his law on my heart and practice it in my life,” Christopher writes. “When I record my transactions I can see from day to day whether I comply with that law, for he tells me in his holy word.”

He attended the Bethel Union church gatherings for mariners, as he himself had been a seaman since 1765, when he began his apprenticeship under his Uncle Job, a successful merchant in Boston.

Church was often held on docks of boats when the weather was nice enough or in members’ homes when it was too cold or rainy, according to Christopher.

While it is unclear whether Christopher belonged to a church that is still in existence today, Downtown is currently home to two maritime ministries: The Seamen’s Church Institute (affiliated with the Episcopal church) and the Mariners’ Baptist Temple. There is no mention of Trinity Church in his diary. It is the oldest formal parish in the city, established by a charter in 1697 by King William III of England.

Christopher had a particular concern for the seamen, as he had spent most of his adult life as a merchant or in the Navy. He participated in the sinking of the ships in the New York Harbor to block the British during the Revolutionary War.

Michael J. Crawford, a maritime historian who was impressed by Christopher’s details on the navy, published Christopher’s first journal in 2002, said Charles. The book appeared under the title, “The Autobiography of a Yankee Mariner: Christopher Prince and the American Revolution.”

With the Revolutionary War long over by 1821, along with his seafaring days, Christopher describes focusing on his job as superintendent of the “Hospital” in Downtown at that time. New York historian and tour guide, Joyce Gold, said that it was most likely New York Hospital, now on E 69th St. At that time however, it would have been located in Greenwich Village and would have been the central hospital for Downtown. He held the position for some 13 years, even though he was in his 70s.

He survived the Yellow Fever pandemic of 1822, when death swept through the city on a jaundiced wave. Many people fled Downtown for the Village, which was relatively untouched by the fever.

“Downtown then would have meant south of Canal St., everything north was farmland or wasteland,” Thompson said.

Gold said that it was during the pandemic that the Village was really settled overnight. While it was common for people to move out there for their health yearly, she said many people who moved in 1822 decided not to return.

“There was an article then which said, ‘I passed a wheat field on Friday…’ and by Monday it was a boarding house able to fit 500 people,” she said.

Gold said that nearly 300 buildings that stand in the Village today were built around 1830, compared to four or five dated before that time.

“The sickness and deaths has caused many families to move out to Greenwich,” Christopher writes in August 1822. “Mrs Coit which I have named in the 51 page, is in an alarming situation, she is in the vicinity where the fever commenced, and no means to move — and some of her children are sick and she still unwell; I told her she must move from there, she said I have no means to move and I do not know where to go — I told her to put up all the furniture she wanted and I would go to the Corporation and git a place for her at their expence, and left her and went to the board of health and received orders to move her out to Kipps bay at their expence, and they would support them as long as the fever prevailed, I went and moved them all out immediately — Mrs Webb has moved to Long Island and I am left alone at her house where I board, but at present nothing will induce me to move from there until I git all away who are helpless, and friendless.”

He remained at his 19 Maiden Lane residence, now a bank and apartments, until Sept. 2 1822 when he moved in with his cousin Dr. Prince on 20 Cherry St. — currently Knickerbocker Village — after a total evacuation of Downtown, including the closing of businesses and banks. At the time, Thompson said, Downtown was a huge mixture of residential housing, factories, and shops. While Gold said that it was the first time people began to commute to work, Thompson said the commute was still hard and most people chose to live close to where they worked.

“Even people who owned the factory lived near it and put up with whatever noise and smells their factory produced,” he said.

He moved back to Maiden Lane on Nov. 5, when the businesses reopened, effectively relieving the threat of the Yellow Fever.

The governor designated the holiday of Thanksgiving at that time, and in 1822 it fell on Dec. 5 in New York. Although most fell on Thursdays, only one Thanksgiving Day fell in November in the five years Christopher writes of. Thursday Nov. 24 was declared the Day of Thanksgiving in 1825.

On April 29, 1823, Christopher moved to 108 Gold St., where the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development now sits, and a year later, he moved to 80 Gold St. — now the site of a Southbridge Towers building — where he remained for the rest of the journal.

The buildings of Downtown were far shorter than the buildings we know today. According to Thompson, they would not have been higher than a reasonable person would be expected to climb the stairs. There were also structural issues with building up, as the walls supported the building without reinforcement like the steel we use today. Even with the shorter buildings, however, he said people still ran into problems like fire ladders not being able to reach a roof of a building.

By 1824, there was another bout of illness in spring and in August, the Marquis D’ Lafayette came to New York City. Christopher met with him on Aug. 17.

“After I had performed the duties at the Hospital, I went to the City Hall, and took the Marquis D La Fayette by the hand, and bid him welcome to the UNS [what he called the United States]. And told him I had the honour to sail in the first vessel which bore his name,” he wrote, “She was a ship of war, and saluted him in Rhode Island: but the crowd was so great, I could not converse with him on the subject. As that was in the year 1778, he might not have remembered, all the particulars.”

He also helped open the Erie Canal on Nov. 4, 1825.

“The Erie Canal is a huge boost to New York City finances,” Gold said. She said that it is arguable that it spurred the city’s exponential growth from that point out. She said that in 1820, New York City was listed as the most populated city in America, and it began its northward expansion on the island of Manhattan.

He must have been blessed with long life and good health from his mother, who wrote to him frequently. She outlived his brother John, who cared for her and died at 56. Whether Christopher Prince died around 1825 or 1826 or merely started another journal is a mystery, as no death records have been found for him.

“Christopher appreciates his country, his family and friends, and of course his God,” Charles said in the introduction he wrote for the journal. “His love and concern for his fellow seafaring immortals is a common thread through this period of his aged life in that ‘sinfull’ city of New York.”

Charles said he was excited to find out so much about the history of his family.

“Eighteen of the 102 people on the Mayflower were our relatives,” he said in awe.

The full journal can be read at https://www.mysticseaport.org/library/initiative/PageImage.cfm?PageNum=1&BibID=35642.