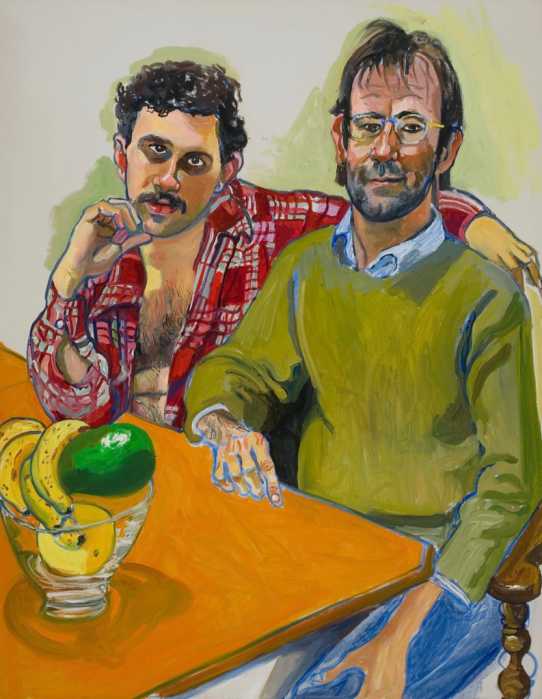

By Bonnie Rosenstock

Most people would want to forget a near-death experience. But for Vado Diomande, the miracle of surviving inhalation anthrax was a cause for great celebration. On Feb. 17, a year and a day after collapsing at a Chinese restaurant after a performance in Mansfield, Pa., Diomande threw himself a big party, or “kekene,” a word in Mahou, his native language, for “a gathering of creative energies.”

Along with his 16-member Kotchegna (“messenger”) Dance Company of dancers and drummers, Diomande, 45, invited 20 fellow artists from his native Ivory Coast living in the U.S. to participate. Or as his wife, Lisa, announced at the end of the two-hour-plus spectacular of unbridled exuberance, “It’s a new tradition to gather all the Ivorians once a year on the anniversary and just blow the building apart.”

And blast to the rafters they did. The stage at the Helen Mills Theater at 137-139 W. 26th St. seemed too small and low ceilinged to contain the colorfully costumed dancers, drummers and singers. When Diomande performed the Mahouka people’s “Tall Mask of the Sacred Forest” dance on high stilts, which required feats of strength, agility and balance — walking on his hands, doing back bends, high kicks and other seemingly impossible contortions — his presence embraced the entire theater. Hard to believe that this was his second show of the day, after a mere two-hour break.

“The outpouring of love and support he received in New York makes him feel like he belongs here, like New York is really his town,” Lisa Diomande said.

As his wife told it, there is no discernible difference between her husband’s pre- and post-anthrax energy level. He has a busy schedule of teaching African dance and drumming at three Manhattan dance centers. A few months back, he performed in Japan for 10 days, and just a few days before these two shows, he gave three rousing performances at the Pennsylvania hospital where he had recovered.

After Diomande’s six-week stay in the hospital, the couple lived in New Jersey with Lisa’s brother-in-law and his wife for four months while they tried to figure out their next address. They could not return to their rent-stabilized fifth-floor walk-up at 31 Downing St. in Greenwich Village because the heavy bleaching decontamination of all their possessions would have furthered endangered Diomande’s health. In August 2006, the Diomandes moved into a basement apartment with private access in a big complex on W. 141st St. and Lenox Ave. in Harlem.

“We are not used to so much room,” said Lisa Diomande. “There are distinct advantages, but learning to adjust to triple rent is difficult.”

They were able to salvage some of their furniture, scarred with bleach marks, but most of their porous items were unusable. Friends pitched in to give them furniture and appliances.

In addition, Diomande was given a place to work, rent free, on 30th St. until July. He has room to store and work on his drums. Diomande is also considered a master drum maker. It was either four goatskin hides, which he brought back from Ivory Coast, or cowhides purchased in New York, that were the suspected — and still unknown — cause of his illness.

Despite all the assistance, Diomande has virtually had to start over. He lost most of his costumes, masks and drums, including many old, invaluable and irreplaceable ones that he no longer played. The fumigated costumes that were returned had a noxious chemical odor that didn’t wash out. Others were faded beyond use and still others just fell apart upon touch.

“I don’t have enough. That’s why I say thank you with this show,” explained Diomande. “But at the same time, I want to get some money together to buy new costumes and drums.”

The Diomandes have decided not to pursue legal measures against the city, state and the Department of Health for their conduct and handling of this episode. As Lisa Diomande said, “There were so many good things that came out of this that far exceeded the trauma and terrible shock of Vado’s close call.”