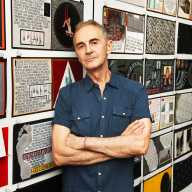

Upper East Side Tracy Morisada, is one of the rare New Yorkers who regained her apartment after being evicted.

But reclaiming her tiny studio entailed a terrible, nearly two-year nightmare in which she lost all her possessions, from her passport to her computer.

Her saga illustrates not only the lengths some landlords will go to reclaim rent-stabilized apartments, but how quickly a vulnerable renter can be stripped of all they have. .

Morisada, 81, had been taken to court by her landlord for falling behind on rent and was given more time by a judge to gather up the arrears on her then-$899 a month studio when she was mowed down by a bicycle in Central Park on July 27, 2013.

She was gravely injured, with a traumatic brain injury, multiple rib fractures, a facial bone fracture and other traumas. Despite her condition, she had the presence of mind to tell staff at New York Presbyterian Hospital she was in the midst of a housing court case. A social worker informed her landlord, BLDG Management Co., Inc. by phone and in writing of her condition, requesting her case be postponed.

Instead, BLDG listed her walk-up apartment as available for renovation on Aug. 1. When she failed to appear in court on Aug. 5, the landlord didn’t explain to the judge why she wasn’t’ there. Instead, BLDG obtained an eviction order, and swiftly moved all of Morisada’s possessions — her silk kimono, computer, all her identification, gold jewelry and a prized mink coat (“it was a good one!” she recalled) into a storage facility and began renovations.

Neglecting to tell the judge why Morisada failed to appear constituted “a fraud upon the court,” said Morisada’s lawyer, Jason Blumberg of MFY Legal Services.

Morisada was recuperating in the Mary Manning WalshHome, on York Avenue, when a social worker performed a home inspection on Oct. 25 to make sure she could be discharged safely, and discovered there was no home for Morisada to return to; her apartment had been gutted and was about to be occupied by a new tenant.

Nursing home staff moved swiftly to obtain legal representation for Morisada through a pilot program at The NYC Department of the Aging, hooking her up with MFY Legal Services.

A judge vacated her eviction in March 2014 and ordered that she return, but also ordered her to pay all her back rent. Mary Manning and MFY — hobbled by Morisada’s lack of personal documents — spent a year cobbling together funds to pay the metastasizing rent arrears and enrolling Morisada in programs to supplement her Social Security check so she wouldn’t fall behind again. Because all her belongings had been auctioned off for nonpayment of rent without her knowledge, advocates also had to furnish the vacant unit..

“She got a partially renovated apartment out of it!” said Lawrence Wolf, the lawyer for BLDG Management, who denied that he or his client did anything wrong. As for the judge’s “troubling” finding that BLDG failed to inform the court of Morisada’s hospitalization, Wolf said: “There was a judgment against her and a warrant. She couldn’t pay the rent.” He blamed the nursing home for a lack of vigilance over her belongings saying, “they let her possessions be sold off.”

“Had the landlord not illegally evicted Ms. Morisada, her belongings never would have been at risk,” said Jon Goldberg, a spokesman for Mary Manning. Goldberg called Wolf’s defense “a desperate attempt by the landlord to divert attention away from his own calculated and improper actions and on to those who worked so hard to ensure that her legal rights were protected, get her the financial and other assistance she needed, and get her back to her rightful home.”

Morisada “never would have gotten home without” the efforts of Mary Manning employees, who first filed court papers on her behalf, obtained a Medicaid waiver for her and worked arduously not only to reclaim her home, but her vanished possessions, and, when they couldn’t, filed numerous complaints, added Blumberg.

Her story points out why all vulnerable seniors need court-appointed lawyers in housing cases, said MFY director of development and communications Dolores Schaefer, who is a fan of the “right to counsel” movement. “Landlords are desperate to get these rent stabilized apartments back,” she said, often so that they can hike rents and turn them into market-rate units for new tenants.

The stakes are especially high now because “there’s an emerging trend of demolishing an apartment the minute (landlords) get a tenant out so a judge can’t put (renters) back in,” added Blumberg, who would like sanctions levied upon landlords who do this.

Blumberg is still steaming over BLDG’s “chutzpah” at asking the court to rule that Morisada reimburse BLDG for the unrequested renovation that was claimed to have cost $20,000 to $30,000. (The judge ruled the landlord had “no decent or equitable basis” to request such a thing.)

Morisada, who said she came to the U.S. from Japan in 1963, is relieved to be back in her snug accommodations (“it’s like a dorm room!”) she has occupied for more than 35 years. During her extended nursing home stay, she was the only resident allowed to venture out on her own without an escort. “I had an ankle bracelet!” she said. “I was a three-time escapee! … What bothers me about the nursing home is no one there was thinking about the future. I’m thinking about the future,” she said. And now that she is home, she said, “I can relax.”