BY JERRY TALLMER

Irish playwright Creedon ‘good going on great’

When I was a kid, if a girl gave you the air, there was always some wise guy cheering you up with the mantra: “You know what they say about women and streetcars — there’s always another one coming along.”

You could more seriously, and more maturely, apply those words to Irish playwrights. The damn thing is, unlike certain non-Desired streetcars, those Irish playwrights (from Yeats and Wilde and Synge and Shaw on down to now) are always good going on great, and the latest in that endless chain is the all but unknown (in America) Cónal Creedon.

Unknown no longer, thanks to Ciaran O’Reilly and Charlotte Moore’s blessed jewel box of an Irish Rep — where Creedon’s short, idiosyncratic “After Luke,” and even shorter, punchier “When I Was God,” comprise a disturbing two-hour double-bill.

Idiosyncratic?

Bite off any hunk of either work; it’s all as chewy as leather yet weirdly digestible. “After Luke,” set in the outskirts of Cork City, on the southern coast of Ireland, looks in on a Dadda, crusty proprietor of a small auto-body shop, and his two grown sons: the mechanically gifted, semi-articulate elder, called Son (as in Horton Foote’s “”Dividing the Estate”), though his name is not Son; the younger and slicker, not to say shiftier, is called Maneen (“little man”), though his name is not that.

We never learn their real names. We never see their mother, who has an appointment with destiny in the chicken coop.

We see, in Son’s retelling, the prize chicken named Reddy who with its beak helps Son strip down cars, and who (the chicken) is slaughtered, just for meanness, by Maneen, the pop-out, pop-in wandering offspring fresh back from the gaudy fleshpots of London. Maneen also steals — that is to say, lays — Son’s wished-for girlfriend.

We see and hear, via the three male narrative roles, a simulacrum of St. Luke’s parable of the Prodigal Son hopscotched to a long-starved and bloody Ireland suddenly finding itself the economic strong man of Europe.

Fathers and sons. For instance:

Son is driving Dadda — boastfully “freewheeling” (coasting) all the way downhill to the Glen Hall — for Dadda’s treasured once-a-week Bingo game.

DADAA (to audience):

How in the name of Christ did I rear a half wit?

A good lad. Don’t drink. Don’t smoke.

Never had as much as an ounce of trouble outa; him —

Strip a car down to the chassis in a half a day, so he would.

Happiest out tinkering with cars? And how bad…

SON: Speed bump!

DADDA:

How bad indeed?

Brain of a mechanic — the hands of a surgeon.

The other fella? Maneen?

They’re like chalk and cheese. Chalk and cheese.

Maneen’s as bright as a button. Up there he have it…

Mind the cyclist, Son!

The fella on the bike!

Mind the fella on the bike, will ya!

Jeezus!

SON: Speed bump!

Whereas in “When I Was God,” another glimpse of the universal built-in father/son civil war, the manifestation is not in terms of chickens or gear boxes but such cherished spectator sports as hurling, soccer, and (yes!) table tennis.

Here the dialogue is terse and repetitive right up to the edge of mania, as Mother and Father argue which of those sports their young son Dinny should go out for, and whether he’s also to go to college or to work.

MOTHER: You thinks you knows everything!

FATHER: Sur’ Jesus! look at yourself, Missus!

MOTHER: What about me?

FATHER: You thinks you’re always right!

MOTHER:

I thinks I’m always right?

I knows I’m always right…

Now he’s going to college,

And no more about it!

FATHER: He will not!

MOTHER: I said he will!

FATHER: Well I said he won’t!

MOTHER: He will!

FATHER: He won’t!

MOTHER: He will!

And of course Dinny (same actor as Mother) will go to college, and will take up first soccer and then table tennis, after failure to master the violence-prone hurling (a close relative of lacrosse) that his father worships — and he’ll wind up as a famous soccer referee bedeviled by the ghost, or memory, of his deeply disgruntled dad.

None of this would be unfamiliar to, let’s say, D.H. Lawrence, or, for that matter, George Orwell. What hasn’t been heard before is the thorny voice of 48-year-old Cónal Creedon of County Cork, Ireland, who, from all reports, is a lot gentler in the flesh than on paper.

“I had only met him on the telephone until he came over with his partner” — a lady named Fiona — “for a week during our rehearsals,” says Tim Ruddy, the director of the twin-bill at Irish Rep. “He’s a real gentleman, a lovely guy, incredibly gracious; went to every performance.”

The only head shot of Creedon that this writer could scare up from Google revealed a face rather like an Irish potato. Ruddy describes him as “average height, stocky build, more on the order of Brendan Behan than Samuel Beckett.”

Yet Ruddy, himself a County Mayo man, had never heard of Creedon until being asked, last year, to direct a stripped-down black-box American premier of something called “When I Was God” for an Irish theater festival at Greenwich Village’s Manhattan Theater Source.

What he found out was that Cónal Creedon was a documentary filmmaker and novelist as well as playwright.

“Cork is a fiercely proud city,” says Tim Ruddy, noting that County Cork was the home sod of martyred Michael Collins. “When Cónal came over this time, he had T-shirts made up for all of us [actors and director] that featured a red star — a Chinese Communist star — and the words ‘Republic of Cork.’ ”

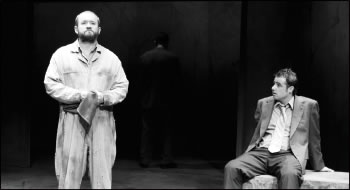

The several roles in both ends of the bill at Irish Rep are fulfilled by Gary Gregg, Colin Lane, and Michael Mellamphy. More power to them — and to Charlotte and Ciaran’s fiercely proud Irish Republic of West 22nd Street.