BY YANNIC RACK | On a Saturday in March more than a century ago, around 500 workers were crowded into the top three floors of an industrial building at the corner of Washington and Greene Sts. in Greenwich Village.

Mostly young Italian and Eastern European immigrants, many of them women, they had shown up for work like any other day.

But many would not return to their families that night and instead fell victim to one of the deadliest industrial tragedies in the country’s history, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911.

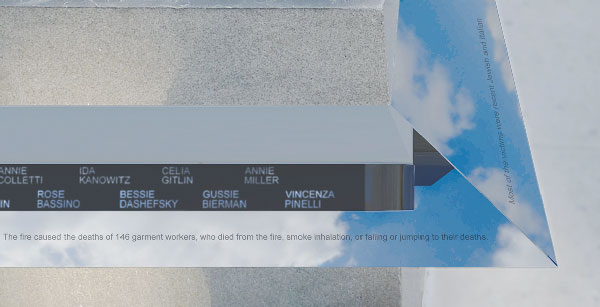

The fire not only claimed 146 lives, but also prompted a wave of lasting labor and safety reforms.

“This was a Saturday, I imagine them walking to work, glad that it was the end of a very long week,” said Suzanne Pred Bass, a psychotherapist on the Upper West Side whose great-aunt Rose Weiner perished in the fire.

Rose’s sister, Katie, survived the tragedy and later testified at the trial of the factory’s owners, who were acquitted of any wrongdoing.

Katie Weiner also told the story of that day to her great-niece before she passed away in the 1970s, which is why Pred Bass is now working to get a lasting memorial installed at the site of the fire, at 29 Washington Place.

“For us family members, the tragedy is still keenly felt,” she said. “And the idea that there was going to be a memorial that really highlights this tragic event that spawned terrific reforms is deeply meaningful for us.”

Pred Bass is part of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, a group of the victims’ descendants, labor advocates and volunteers that was formed seven years ago to organize the fire’s centennial commemoration. Out of the planning for that event came the idea to construct the memorial.

“We have exported the tragedy of Triangle. Garments are not made in this country like they were in 1911,” said Joel Sosinsky, a retired city attorney who is the coalition’s secretary.

In fact, the former factory building is now used as biology and chemistry laboratories by New York University.

Sosinsky noted that although disasters like the Greenwich Village fire don’t occur in the U.S. anymore, they do still happen elsewhere around the world, which makes it a contemporary issue.

“You go to a place like Bangladesh, and they don’t have the same rules and regulations and safety protections for workers we have — which are a direct result of what happened at Triangle,” he said.

The project already has support from a range of local politicians, like City Councilmember Margaret Chin, Assemblymember Deborah Glick and Borough President Gale Brewer, who is also listed on the coalition’s advisory committee.

“The Triangle Shirtwaist fire was the worst industrial disaster in the history of the city — and one of the worst ever in the nation,” Brewer said in a statement.

“It’s fitting that we honor those who died and recognize the role that the tragedy played in improving working conditions and spurring the growth of labor unions.”

N.Y.U. also supports the plan and has been working with the coalition since 2012, helping it set up a competition to find a design for the memorial, according to a university spokesperson.

Richard Joon Yoo, an architectural designer who lives in Queens, submitted the winning proposal together with a friend, Uri Wegman, an architecture professor at The Cooper Union.

“For almost a hundred years, all that has existed [in memory] of the fire were these three plaques at the corner of the building,” Yoo said, adding that he was immediately fascinated by the project.

“A memorial, especially in New York, and especially for something that is so desperate to be memorialized, was just an awesome project to take on,” he said.

The design consists of three sets of polished steel panels running along the building’s facade and serving several functions.

One panel, installed at pedestrian-hip level, tells the story of the fire in one line running around the entire outside of the building, and also reflects the names of the victims — which are etched into a second panel installed roughly 17 feet above the sidewalk.

The third panel, running vertically up the building’s corner to the eighth floor, is supposed to reflect a “sliver of sky” and attract curiosity from afar.

At the time of the design competition, around two and a half years ago, Yoo said the idea of the memorial was still somewhat abstract to him. As soon as he became immersed in the project, however, he discovered he had a personal connection to the fire himself.

His wife’s aunt, it turned out, is the daughter of Theodore Kheel, a prominent attorney and labor mediator who, Yoo said, played a part in the negotiations that were a consequence of the fire.

“It’s amazing, that’s actually a pretty direct connection, which completely shocked me,” Yoo said.

“I’ve been really humbled by how deeply this runs in so many directions.”

The Greene St. building is landmarked, so the memorial design would have to be approved by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. A spokesperson for the commission did not return a request for comment.

The coalition’s main goal now is to raise the cost of building and maintaining the memorial, which will cost about $2.4 million, according to Sosinsky.

He hopes they will be able to obtain funding from many sources, including labor unions and even the state Legislature or the City Council, which could fund the $1.4 million construction cost in its annual budget.

“We also hope to raise a lot of money from workers around the country — a $25 contribution would give a garment worker or a teamster, or somebody else who is a labor advocate, a piece of this memorial,” Sosinsky said.

For him and the other volunteers involved in the project, the memorial is simply a continuation of their efforts.

The group is already involved in the annual commemoration ceremony at the site of the fire, which was started more than 50 years ago. The centennial celebration, in 2011, was also a big success, attracting thousands of people.

“We don’t usually get the same crowds as then, but it’s increasing every year,” Sosinsky said.

But he added that remembering the fire once a year is not enough.

“The reason we need a memorial is because people walk by that building every day and do not have a clue what happened there and what it led to,” he said.

Labor globally speaking, also, will be inspired by the memorial, he said.

“Union activists [abroad] look to us and say, hey if we can get something like this done in our country, people who go to work in the morning will have a better chance of coming home at night.”