By Jerry Tallmer

Unusual exhibit chronicling life of Ellen Terry and her famous relations

Dynasty. A much misused word. Unless you are talking about this family.

Imagine this: Ellen Terry and her grand-nephew John Gielgud, in one room together. Then add Terry’s children: Edith Craig a suffragist; and Edward Gordon Craig a path-breaking stage designer. Imagine that dynasty.

There is such a room, the Donald and Mary Oenslager Gallery of the New York Library for the Performing Arts, at Lincoln Center, and these four remarkable people are there, in words (written and spoken), photographs, prints, drawings, artifacts, thru Aug 21.

Let us start, just for kicks, all the way at the back, on the rear wall of the large room where, among other materials, there is a two-page 1953 promotional piece from MGM in the form of a mock newspaper, the Daily Chariot, which looks and reads like the New York Daily News of those years.

Headline: “Caesar’s Stabbing, Bloody Riots, Seen as Prelude to War!”

Inquiring Photographer’s inquiry: “Do you believe in the Ides of March?”

Editorial: “Quo Vadis, or What’s Next?” (almost Stoppardian, that one).

What this Roman tabloid is promoting is the MGM movie “Julius Caesar,” in which James Mason plays Caesar, Marlon Brando plays Antony, Deborah Kerr plays Portia, Greer Garson plays Calpurnia, and John Gielgud plays — of course! — yon lean and hungry Cassius.

Now let’s return to the front of the room and the start of the exhibit.

On one wall, a broadside announcing a performance of “Macbeth” at the Princess Theatre, Oxford Street, with (in the smaller type befitting a child) Miss Ellen Terry (then age 8) as Fleance, the soon-to-be slaughtered son of Banquo. Hard by that, a Julia Margaret Cameron photograph of twenty-ish, soulful, virginal Ellen Terry, head bowed, fingering her locket.

Opposite wall: A large poster (“Charles Frohman presents . . . “) of Ellen Terry all in white (gown, cap, parasol); a likeness of her declaiming in “Cymbeline”; a photograph of her as Cordelia — a rather ripe Cordelia — to Henry Irving’s Lear. And, bizarrely, a domesticated, unflattering Ellen Terry at the ironing board in Sardou’s “Madame Sans-Gene.”

She toured America with performances and lectures (Carnegie Hall, the Hudson Theatre, the Legal Aid Society), she toured the U.K. provinces. One pinkish-yellowish flyer for an appearance at The Kiosk, Lowestoft, is topped with an advertisement: “Artificial Teeth!”

Bernard Shaw comes into this montage only peripherally, via a program for Miss Ellen Terry and company in “Captain Brassbound’s Conversion,” which GBS wrote for her. There is case after exhibit case of images of her, photos of her, in costume, in furs, on stage, off stage; letters, scripts, prompt books.

And, finally, this: A 1906 cartoon from Punch in honor of her Jubilee Season, 50 years after her debut as Fleance. Mr. Punch and Mr. William Shakespeare do a little tributary dance over the caption: “Fifty Years a Queen.” She, in fact, kept acting into her late 70s, and, as noted, also brought forth two children without benefit — or burden? — of marriage to their papa, architect and stage designer Edward W. Godwin.

Shaw briefly reenters the room with a dry appraisal of the comparative accomplishment of those two children as adults:

“Gordon Craig has made himself the most famous producer in Europe by never producing anything, while Edith Craig remains the most obscure by dint of producing everything.”

We see a photo of Edith Craig as a trim, alert, handsome young woman in her late 20s — in a ruffled collar and wide-shouldered jacket — and of Edith at 45, gray-haired, sober, still handsome, but we do not see (did I miss it?) a photo of, as the exhibit press release specifies, “her longtime female partner, writer/editor Christopher St. John.”

In point of fact, as I learn from Google, Christopher St. John (born Christabel Marshall) was a notable personage in her own right, editor of the Shaw/Terry correspondence, discerning early admirer of the talent of John Gielgud, warrior in the struggle of votes for women. The domestic setup was actually a menage a trois: Edith Craig, Christopher St. John, and the painter Clare Atwood, another amazing character, all under one cottage roof.

Gordon Craig enters the picture here with a huge “I” — not I for me, Gordon Craig, but for Isadora. It’s a 1924 print by him — to knock your eye out (sorry about that!) — to which he finally inscribed his name in 1953.

Near this are three photos of Isadora, in one of which, a right profile, she looks astonishingly like Vanessa Redgrave — who of course played her in the 1968 Karel Reisz film in which James Fox portrayed Gordon Craig. There are also Craig’s woodblock print of Isadora looking African, and fairy-like collotypes of her, in adjoining cases.

In this wall, too, is a pair of headsets through which you may hear short recordings by Ellen Terry and long recordings by Gordon Craig, in their own voices. Hers are only three and a half-minutes long, thanks to the technical limitations of her era, while his stretch to 12 minutes or longer. Because of which — Gordon Craig droning on — I never got to hear her.

But on the opposite wall, where there’s another set of earphones, I did get to hear John Gielgud beautifully fluting away in “The Ages of Man” — a one-man show from Shakespeare which had knocked me out when, an inspired, inspiring, smallish man with a winning bald patch where a crown might sit, he so passionately did it in New York in 1957.

That was 10 years after he’d knocked the whole city out with his fabulous, definitive production of Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest” staring himself, Pamela Brown, and Margaret Rutherford.

Gracefulness is all (if you also have genius, that helps). John Gielgud added luster to every film he ever made, beginning with Albert Hitchcock’s “Secret Agent” (from Maugham) in 1936, and the next year Guthrie McClinock brought Gielgud to Broadway for “Hamlet,”

There is a letter on this wall, from Gielgud, hand-typed, in February of 1937, in which he thanks the whole “Hamlet” company for that experience. “I must England,” he writes. “You know that.” Only Gielgud could pack so much breeding and generosity of spirit into six words.

A few highlights

Ellen Terry (1847-1928), great British actress, great beauty, great epistolary (i.e., intellectual) amour of George Bernard Shaw.

Edith Craig (1869-1947), actress, director, costume designer, producer, founder of the Pioneer Players, feminist, suffragist, essayist, daughter of Ellen Terry.

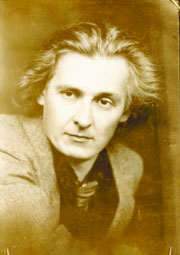

Edward Gordon Craig (1872-1966), artist, illustrator, publisher, author, theatrical theorist, director, pathbreaking stage designer and stage-lighting developer, mentor of Eleonora Duse, lover of Isadora Duncan, all-Europe seed-scatterer (of offspring), son of Ellen Terry.

John Gielgud (1904-2000), great British stage and screen actor, Shakespeare sower (as one sows grain for a starving humanity), Tony winner, Oscar winner, Olivier winner, writer, artist, director, anecdotist, great-nephew of Ellen Terry (grandson of her sister Kate).

Uncredited proof photograph, ca. 1920

Above, Edward Gordon Craig. Right, John Gielgud in the title role of Hamlet in the 1936 Broadway production.

All photos courtesy of New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Billy Rose Theatre Collection

For More: https://www.amny.com/news/hold-the-frappucinos-give-back-community/