By Sara G. Levin

The rapper 50 Cent is still holding a baby and a gun is still sticking out of his paints in Andre Charles’s mural on E. Third St. and Avenue B, which Charles told The Villager he would paint over last week. Complaints about the gun by some local residents, including fellow muralist Antonio “Chico” Garcia, prompted Charles to add to his Web site a cringing rat over the words “Graffiti artist calling the cops” with a link that highlights Garcia’s quotes in The Villager two weeks ago.

Garcia did complain to local police, but only after he first expressed his dislike of the painted weapon to Charles, Garcia said. While Garcia opined that Charles is hyping the situation to attract attention, Charles claimed dissenters weren’t getting the right message — that 50 Cent is a role model. Charles insisted he is waiting for the weather to turn warmer to paint something else, something perhaps even more provocative.

“Little kids looking out onto the bar with a question mark,” Charles said, describing a scene he plans to illuminate with suit-clad bar patrons drunkenly stumbling onto the street. “See what [people’s] reactions are toward that!” he continued, stating that public paintings should reflect real life.

Unfortunate realities in artwork may be all too familiar to Garcia, whose memorials to fallen neighbors have covered the Lower East Side for decades. According to him, Charles’s Web site posting is a stunt in his attempt to take over walls on the Lower East Side once associated primarily with Garcia’s own signature.

“I don’t care what [Charles] thinks of me,” Garcia said. “I’m not trying to compete with anybody, I’m just trying to beautify my own community.” But competition for street fame is where graffiti legends come from, and longtime habits may die hard. “Come this summer [Charles’s] walls are coming down,” Garcia warned.

“We used to work together,” Charles said about himself and Garcia. “But you can’t compromise with people who are ignorant.”

Contention is nothing new to the world of street art. Just earlier this year Chico’s own rendering of Pope John Paul II at E. Houston St. and Avenue B was splattered twice with paint. But controversy over Charles’s 50 Cent mural on Third St. points out the precarious position legitimate graffiti artists — those who get paid by building or store owners for their murals — balance between street credibility, artistic license, commercialism and social responsibility. Both Charles and Garcia are often paid for their murals, though they sometimes simply get permission to do a mural without getting paid.

Someone is only respected in the graffiti world if they built a name through personal expression, not being a commercial copycat, according to Downtown graffiti artist Earsnot from Irak Crew. Getting paid for stylistic talent is great, but someone who’s never been associated with graffiti who is paid to copy street style to “reach” a young audience — by doing a soft-drink mural, for example — is a sellout, Earsnot said.

Though Garcia and Charles both gained respect among fellow graffiti artists for their murals and pieces — colorful murals of a graffitist’s name — years ago, they no longer tag — quickly write their names on walls — illegally. All graffiti artists, even those now doing walls that have been commissioned, came from a culture of illegal tagging to be recognized, according to Wilfredo Feliciano (Bio) from Tats Cru, a group of Bronx graffitists who are commissioned to paint murals throughout the city, including the recent “King Kong” scene on Ludlow and Houston Sts. “In graffiti, it’s sort of the process: you tag, you do throwups [somewhere between a tag and a piece — usually quick bubble letters of a tag] and you progress,” Feliciano said. “I understand the complaints of property owners. I also understand the adventure [for kids] behind it… It’s fame. They’re building an identity.”

Charles maintains his 50 Cent wall was unpaid.

A call by The Villager to Paramount Pictures, distributor of 50 Cent’s movie “Get Rich or Die Tryin’” — the ad for which Charles copied in his Third St. mural — inquiring whether the company had paid Charles, was directed to a voice complaint mailbox set up “to monitor recent complaints or comments about billboard advertising.” Jeffrey Velez of Violator Management, a management company handling 50 Cent, said Charles was not paid.

Meanwhile, Garcia makes a living as a City Housing Authority worker, not through his murals, though he sometimes does murals for pay. But illegal stunts aside, both may still be competing, whether intentionally or unintentionally, with other street artists through their murals’ content. Tats Cru’s Feliciano said that although he is not personally friends with Charles (it is rumored Charles ran into trouble with Tats Cru a couple years ago by painting over one of their walls), Feliciano understands the frustration of receiving complaints about one’s graffiti artwork.

“We’ve done murals where we’ve portrayed guns and we got a lot of backlash from the community,” said Feliciano. When the group painted a memorial for a local drug dealer, “White Boy John” on Southern Boulevard, the victim’s mother asked that he be portrayed as a gun-wielding dealer to send a message, Feliciano said. “She wanted everyone to know that her son sold drugs, and that is where it got him. Some people interpreted it as us trying to glorify a lifestyle. But we were misinterpreted. There’s nothing glamorous about that.”

Tats Cru was also blasted when a Hummer ad they painted in Williamsburg was defaced by spray paint declaring “Sellout” and “Hummer = Death.”

Garcia said he was also frustrated at the lack of respect for some of his work.

“They’ll get jealous, pissed off, they’ll start tagging on my stuff,” Garcia said. “It’s all about the money thing,” he said, implying some graffitists envy him because he gets paid. “But I don’t believe that. I think it’s about beautifying the community,” he said of his work.

Contrary to Garcia’s taste for public murals, the East Village and Lower East Side are also popular places to scribble tags for kids from all over the world, said Feliciano. Even though painting pieces is less popular or possible than it once was, he added, the high presence of tags and people traffic in the area makes it a place where graffiti writers want their names seen.

“Kids from [Europe and the U.S.] hit the Lower East Side because they figure that’s where they’ll get the most fame,” Feliciano said. “It’s a short, quick way to make sure people know your name, because that’s where most people will see it,” though he said real legends go “all city” — meaning they have graffiti walls up in all five boroughs.

While some residents complained about seeing kids they suspect are from outside the neighborhood scrawling on the walls of Third St., Earsnot maintained the people who tag in the East Village reflect how widespread graffiti culture is.

“A lot of writers are white because it’s a demographic of kids from all over the U.S.,” said Earsnot said, who grew up moving around in the different boroughs of Manhattan. Though Garcia and Charles may be older, and have left tagging behind, their debate over the mural on E. Third St. may go beyond neighborhood walls for both.

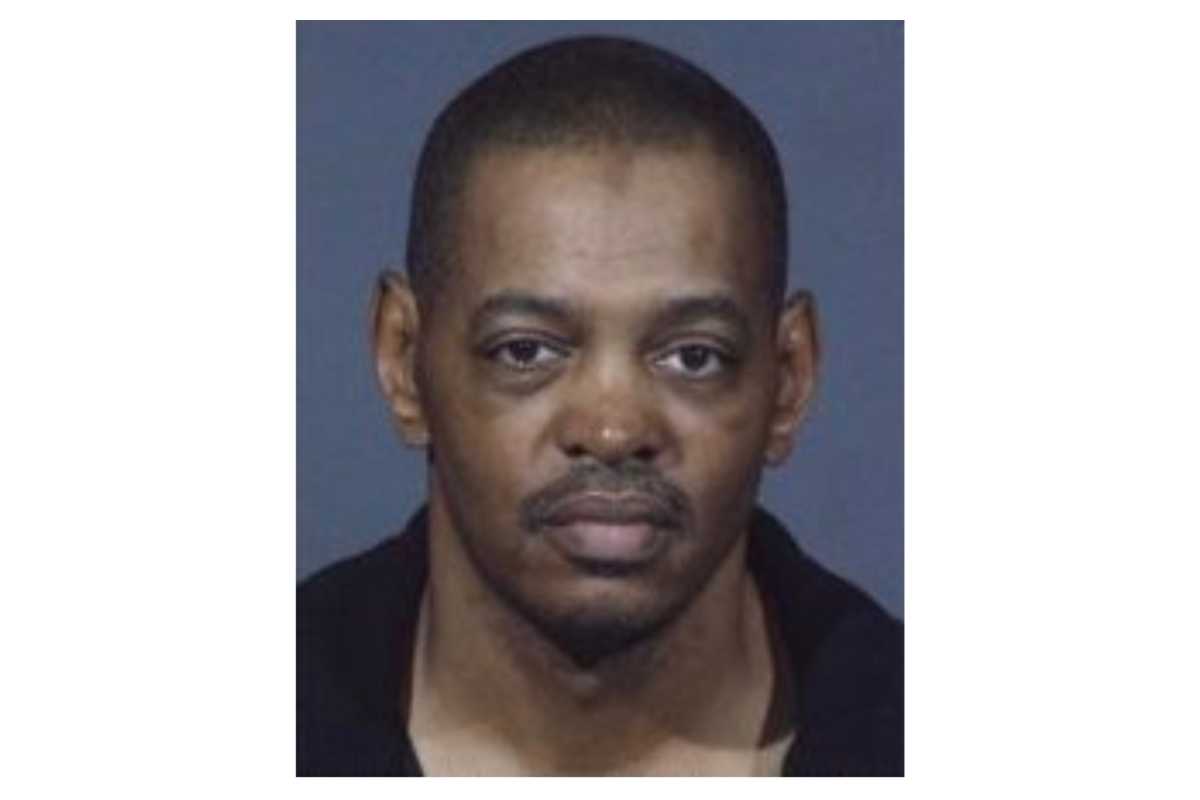

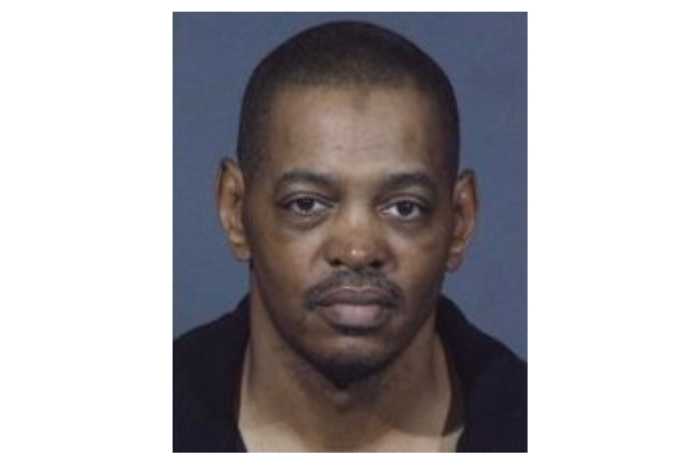

Andre Charles