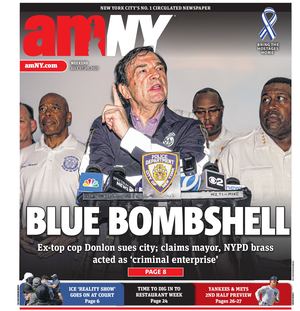

Hundreds gathered at Washington Square Park on Jan. 10 in solidarity with victims of the Paris massacre.

BY ZACH WILLIAMS | Chelsea resident Lawrence Walmsley began the morning of January 7 perusing the news on his iPad, when he came across something that he could not initially believe: a mass shooting in Paris. In another part of the neighborhood, Ingrid Jean-Baptiste received a phone call informing her that two masked gunmen had just stormed the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo.

They were shocked by the coordinated nature of the attack, which left 12 people dead that day, they said. As incidents of violence and murder continued in the subsequent days, the underlying motivations behind the carnage emerged as the world learned that the alleged attackers were two French Muslims inspired by religious zealotry. In the pages of Charlie Hebdo, brothers Saïd and Chérif Kouachi did not see humor in cartoon lampoons of the Prophet Muhammad. They saw a target.

Visual representations of the prophet are forbidden in Islam, but the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo did not care. Staff at the magazine have long delighted in printing caricatures of the powerful. A predecessor publication was banned by French authorities in 1970 for making fun of the death of Charles de Gaulle. A 2011 bomb outside the Charlie Hebdo office followed the publication of an issue guest-edited in jest by Muhammad with a cover reading: “100 lashes if you don’t die of laughter.”

Hundreds of people, mostly French expatriates and their families, congregated at Washington Square Park on the afternoon of Jan. 10.

Their sometimes crude brand of humor had a niche following among French people, but did not appeal to others. On Jan. 7, the magazine’s style of free expression assumed a significance unimaginable the day before.

“It [Charlie Hebdo] was provocative so I was not a big fan,” said Jean-Baptiste. “However I respected the work of the cartoonists. After all, they are artists and I appreciate everyone’s art whether I like it or not.”

Within hours of the Jan. 7 attack, Je Suis Charlie (I am Charlie) emerged from Twitter as the rallying slogan to which millions of people across France would respond. By the evening hours, hundreds would gather in Union Square to express their solidarity with the victims as well as their shared belief that curtailing free speech was the ultimate aim of the attackers.

As people across the world expressed similar sentiments, the Kouachi brothers remained at large.

They were spotted north of Paris on Jan. 8. But it was in a southern suburb of the city where another man, Amedy Coulibaly, fatally shot a police officer and injured another person that day.

The killing would continue.

“It was very overwhelming. It just kept going and going,” said Jean-Baptiste, who is co-founder of the Chelsea Film Festival.

Chelsea Film Festival co-founder Ingrid Jean Baptiste (right foreground) joined a prayer outside after a memorial reached full occupancy on Jan. 11.

She would not learn until Jan. 11 that the father of a friend, Francois-Michel Saada, was among those gunned down by Coulibaly the day before at a kosher market in an eastern neighborhood of Paris. French authorities say there was a link among the three gunmen who all died on Jan. 9 following firefights with French law enforcement. Searches continue for remaining suspects in connection to the attacks.

Seventeen people were dead — excluding the three gunmen — by the time the attacks subsided on Jan. 9, with 21 others injured, making it the deadliest terrorist attack on French soil since 1961. Thousands of miles from her homeland, Albane de Izaguirre could not find adequate comfort among her American friends. She would find solace by standing with her compatriots at a Jan. 10 rally in Washington Square Park.

Several hundred people congregated there, as millions prepared to march in France over the weekend. They would express their solidarity mostly through silence with pens and pencils held up high. Occasionally, they would repeat Je Suis Charlie in unison as they held up signs. Some would battle tears as the crowd sang the French national anthem.

“It’s really hard when you’re not in France,” said Raphael Bord, a resident of Williamsburg. “You see what’s going on but you cannot really participate.”

Though predominately French expatriates and their families, the crowd at the event also included Hell’s Kitchen resident Teresa Cebrian. She said she grew up in Spain amidst the fall out from the 2004 Madrid bombing of a commuter train by an Al Qaeda-inspired group.

On Jan. 10, in Washington Square Park, Charlie Hebdo supporters battled freezing temperature while promoting free expression (predominately through silence).

Prior to that attack, she had thought that terrorism arising from Islamic extremism was a phenomenon relegated to other countries, she said. Even ten years later, she said she does not feel safe from the dangers of radical Muslim militants

“It’s an attack on the freedom of expression in democratic societies and we’ve got to fight against that,” she said of Paris shootings.

The slaughter evoked memories of the Sept. 11 attacks among many people present at the rally. However there is a key difference, according to Walmsley and his French wife, Sophie Thumashansen Walmsley. The 9/11 hijackers were foreigners, whereas in Paris, the attackers rose from a “tiny minority” within a native Muslim community living on the edges of French society.

They were originally welcomed to France as laborers during more prosperous times. But as one generation gave way to the next, many Muslims in France struggled to assimilate even as second-generation citizens. Recently passed laws forbidding Muslim women from covering their faces in public stoked resentment among them. Radical clerics found a ready audience in recent years among disaffected men such as the Kouachi brothers who were children of Algerian immigrants, according to media reports.

French police arrested Chérif Kouachi in 2005 as he attempted to reach Iraq by way of a Syrian-bound flight. Like more than 1,000 Muslim Frenchmen in recent years who have fought in Syria, he wanted to wage jihad, according to media reports. While thwarted in that effort, Chérif would eventually achieve his purported goal of achieving martyrdom ten years later.

Fighting back against such an ideology necessitates a non-violent approach, said participants of the Jan. 10 Washington Square rally. The attacks represent an opportunity to confront this fringe element of French society, according to Sophie Thumashansen Walmsley.

“This could be a rallying cry to get France together again to come up with a new French identity,” she said.

The next day millions of people mobilized across France in similar fashion: toting Je Suis Charlie signs, pens and pencils.

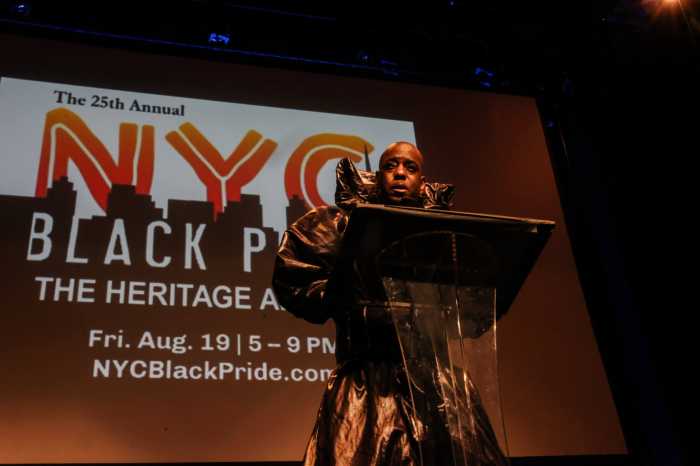

Hundreds more came to Lincoln Square Synagogue near W. 68th St. (on Amsterdam Ave.) that evening to mourn. Among the electeds in attendance were Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and Sen. Chuck Schumer. When the meeting room filled to capacity, one hundred more congregated in a hallway. Soon a hundred more stood outside in the winter cold vainly hoping for admittance.

Sen. Charles Schumer, at podium, expressed support for France and Israel at a Jan. 11 memorial. Front row, L to R: Public Advocate Letitia James, Comptroller Scott Stringer, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito.

As Schumer prepared to speak on U.S. support for France, Jean-Baptiste soon found her own place to mourn. Stuck outside, she joined a dozen others in a quiet Jewish prayer recited from smartphones.

“Right now the only solution is to gather and be united,” she told Chelsea Now earlier that day.

As the workweek began anew, reports of reprisal attacks against French Muslims continued. By Tues., Jan. 13, 10,000 soldiers were patrolling neighborhoods throughout the country and French President Francois Hollande had declared war on terrorism.

That same day, the Charlie Hebdo staff announced that the Prophet Muhammad would once again grace the cover of their magazine. This time though, they would print millions of copies rather than the magazine’s typical circulation of about 60,000.

He totes a sign with a now-famous slogan and sheds a tear of contrition.

“Tout est pardonné,” reads the cover. “All is forgiven.”