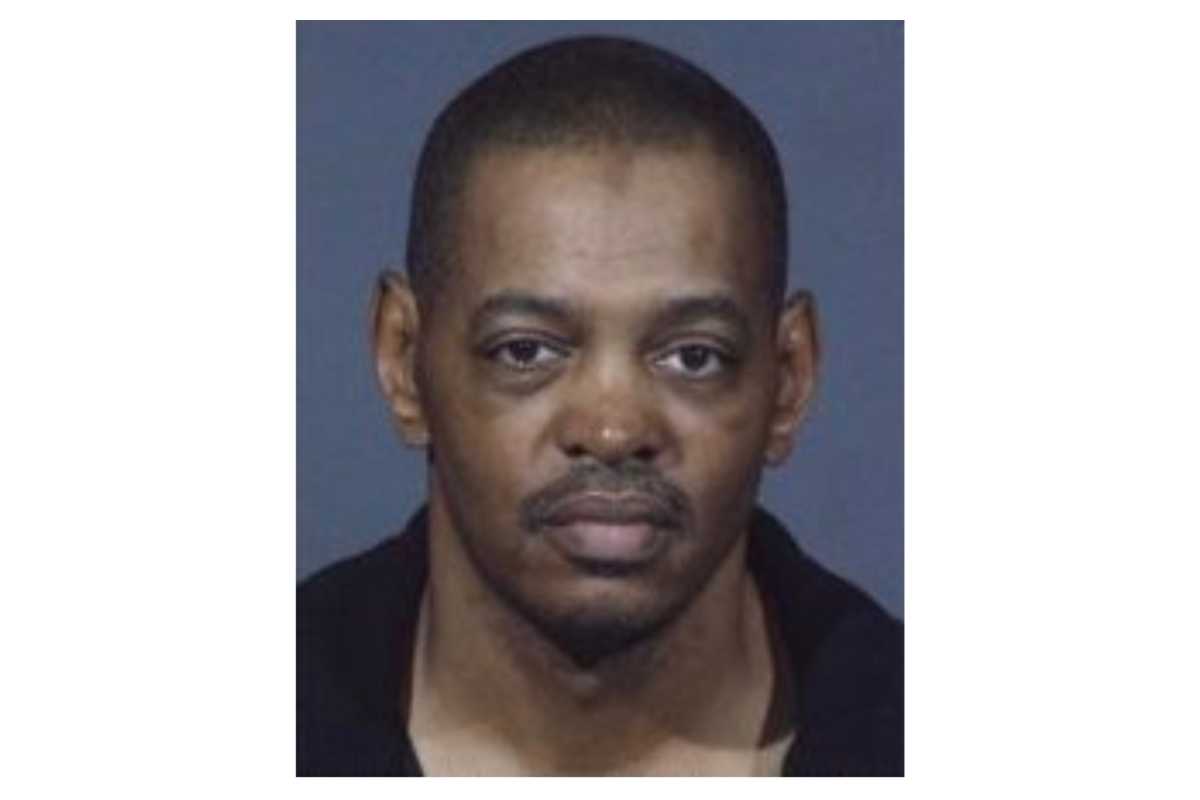

BY CLAUDE SOLNIK | When Judge Jonathan Cataldo announced he would let TV cameras in the courtroom before announcing his ruling in Fernando Bermudez’s case, I felt encouraged. I had known Fernando was innocent for nearly two decades, ever since I wrote a front-page story for The Villager indicating evidence of his innocence. If the judge upheld the conviction for a Greenwich Village murder, there would be little to report. Media would only care if the judge overturned the conviction after Fernando spent 18 years in prison.

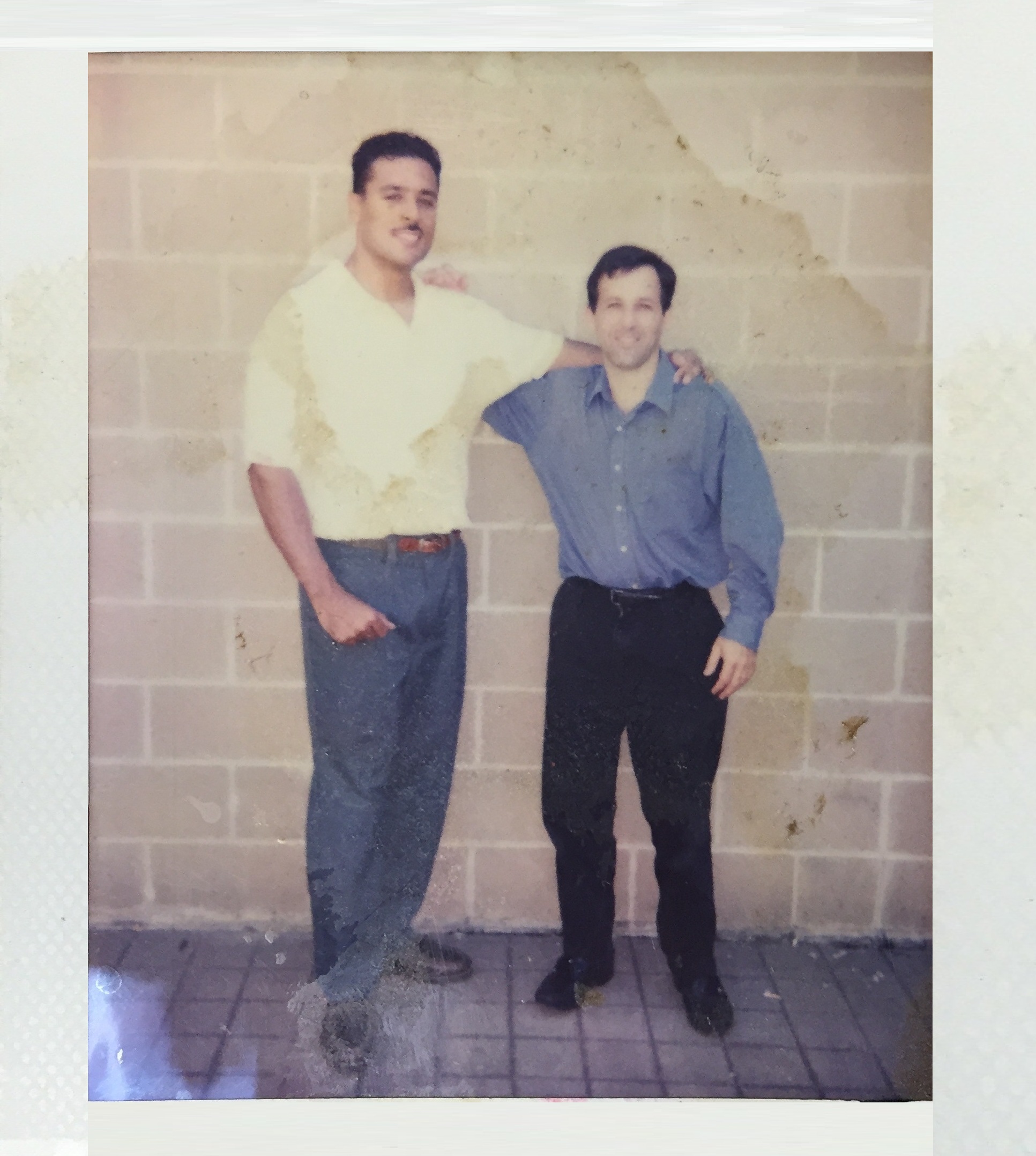

That day turned out to be one of the most memorable, and remarkable, in my life. Justice Cataldo did much more than overturn. He apologized to Fernando and declared him factually “innocent,” not simply not guilty. Fernando was freed soon after. Mike Gaynor, the retired detective who investigated the case, and the few of us who comprised the official-sounding Committee to Free Fernando Bermudez celebrated in a Chinese restaurant. The food was ordinary. It was the best meal I ever had. Lesley Risinger and Barry Pollack, the lead pro bono attorneys who won, were heroes in my book along with MaryAnn DiBari, who fought hard, as well. The Villager played a role in freeing an innocent man.

So, I believe, did I.

While I didn’t forget Fernando (we’re friends), only lately have I become involved in his life and the issue of wrongful conviction again. I wrote a play, “Pedro Castillo Is Innocent,” based on Fernando, with enough fiction to get me to change the character’s name. The show “Making a Murderer” tells one wrongful conviction story. This play, running at Theater for the New City from Feb. 4 to 14, brings Fernando’s case back into my life and, I hope, shows it to others who live blocks from the site of the crime for which he was convicted and exonerated.

While we all talk about the need to move on, this play seeks to show us the human impact of injustice on an innocent man and his family. We can’t just forget what happened after a victory. We need to translate that into a recognition of the true tragedy and cost of these mistakes and a call for change.

I wrote the play because, while Fernando’s victory finished one thing, I see unfinished business in a broken justice system. The Villager when Tom and Elizabeth Butson ran the paper and other media helped free him, by helping attract talented lawyers and forcing the courts to look at the facts more carefully. In Fernando’s case, the media is one of the few things that did its job — and it does have one in the justice system.

Although The Villager put the story on its front page first, The New York Times had the courage to do the same, while he was in prison. “Court TV” reinvestigated, concluding he was innocent. TV stations and other publications weighed in. Why did Fernando remain in prison so long with no physical evidence and an alibi based on a photograph passed around by witnesses, while the main witness identified someone else as the killer?

A federal judge charged with reviewing the case gave it to a low-level magistrate who, I believe, was reluctant to overturn. Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau finally retired after decades of stonewalling and no “conviction integrity” process, clearly demonstrating a problem in the lack of term limits. The state judge handling Fernando’s case retired after doing everything possible to prevent witnesses from recanting. This wasn’t about making a mistake. It was about the cost of refusing to acknowledge and correct one.

Just like the way we pushed with press releases and advocacy to “Free Fernando,” I am using words as weapons and tools once again. “Pedro Castillo Is Innocent” seeks to show how this story exists in the perpetual present and isn’t just about facts, but family. It looks at Fernando during one portion of his life in prison. I left the details of Fernando’s story for Fernando to tell: I believe they belong to him. It fights against the temptation to forget, showing an innocent man in prison and those around him as they deal with an injustice so immense that it makes a person question the sanity of society.

We presented a staged reading at the Studio Theatre Long Island, which Fernando’s mother, brother and sister attended. “That’s Fernando,” his mother said. She was right. I used to sit in the prison parking lot after visits, writing down what he said. I believed he should be heard, and in this play, I believe, he is. I watched him suffer and grow, go from lifting weights to learning new words and lecturing at Harvard, Yale and elsewhere after his release. I was happy that the world wanted to hear the man that nobody would listen to for nearly two decades. He was using words to try to stop people from forgetting and get us to fix a broken system. I would do the same thing. I wanted others to feel as strongly as I did about what occurred and the need for institutional change. Judging by the reaction at a staged reading, that’s starting to occur with audiences.

Theater for the New City, run by Crystal Field, agreed to present the show, in part, I believe, because she likes the idea of a play that “says something.” At rehearsals, I listened as John Torres spoke lines I still remember Fernando saying. I watched Christine Copley, the actress playing a character based on his wife, go through the pain that I remember his wife, Crystal, felt. I watched the director, Danielle C.N. Zappa, and actors keep Fernando in front of me. When people talk about “Making a Murderer,” I think of Fernando and other innocent people awaiting resolution. I also think of Justice Cataldo, who understood it’s important for the world to see what went wrong.

I hope audiences will get a better sense of the injustice done in the name of society and ask that it not be done in their name. I am convinced one of the reasons great injustices occur is that we allow them to be invisible. We need someone to be innocent until “proven” guilty — not simply declared as such.

So many problems that led to Fernando’s time in prison remain. Prosecutors and police who did a terrible job were promoted, although they may have faced an emotional toll, realizing what occurred. Lineups were viewed simultaneously, where witnesses pick suspects most resembling the criminal. Carousel lineups where people step up one at a time are considered more reliable, but not required. Double-blind lineups — where the person running the identification doesn’t know who the suspect is — are a best practice. Neither is the norm. Then there’s a refusal to acknowledge error. We all make mistakes. Admitting one is a sign of a system’s strength.

I don’t believe this play can change anything, but I believe it’s part of an important push for change. If “Making a Murderer” turns into a TV show rather than a call for change, it will be a missed opportunity.

What’s happening is “our” problem. I lost sleep over Fernando’s situation for years as his situation became my problem. Ask my wife or children, who also dealt with this. When I listen to the actors, I sometimes smile, knowing Fernando is free. But by writing this play, I refuse to forget the other Fernandos waiting to be freed — and future Fernandos. I hope others will see the show as the chorus for change grows, until we realize we are all responsible for these wrongful convictions and responsible for bringing about change.

“Pedro Castillo Is Innocent,” Theater for the New City, 155 First Ave., Feb. 4-14. Purchase tickets, $15, at www.theaterforthenewcity.net or by calling 212-254-1109 or at the door.

Solnik is a former reporter for The Villager