BY BILL WEINBERG | It’s started.

Over the past week, agents from Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement carried out raids across several states, arresting more than 600 people — who apparently face summary deportation. Some 40 of these were detained in the New York City area. The raids were the first since President Trump’s Jan. 26 executive order expanding priorities for immigration enforcement. ICE called the raids “routine,” and said most of those detained were “criminal aliens.” But the sense of fear in the city’s immigrant communities is palpable.

This is an issue that especially impacts New York. Nearly 40 percent of the city’s 8.2 million residents are foreign born, according to a 2013 study by the City Planning Commission, “The Newest New Yorkers.” In at least nine neighborhoods, half the inhabitants or more are foreign born. Among these are Chinatown-Lower East Side (taken as a single entity), which clocks in at exactly 50 percent.

On Sun., Feb. 12, hundreds endured freezing rain in Battery Park for a protest against Trump’s ban on refugees entering the country — instated by another executive order, issued Jan. 27. Mayor Bill de Blasio was among those who spoke at the rally called by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the oldest refugee resettlement organization in the country — with its origins on Lower East Side way back in 1881.

Exactly two weeks earlier, on Jan. 29, de Blasio was speaking at a much larger rally in that same place. Some 10,000 filled Battery Park that afternoon to protest Trump’s so-called “Muslim ban” now being contested before the courts. The rally came one day after large crowds of protesters turned out at J.F.K. Airport, where several travelers from Trump’s seven designated Middle East countries were being detained. Simultaneous with the J.F.K. action, there was a demonstration in Brooklyn’s Cadman Plaza, outside the courthouse where a federal judge issued an order barring deportation of the detainees — sparking a showdown between the White House and judiciary.

At that Battery Park rally — on a clear day, within sight of those icons of open immigration, Lady Liberty and Ellis Island — activists joined with metro-area officialdom to repudiate Trump’s move. Organized by the New York Immigration Coalition, the event featured Senators Chuck Schumer and Cory Booker, as well as the mayor. But what made it significant for me was the mass of humanity — more personally impassioned and inspired than at many protests I’ve attended over my life.

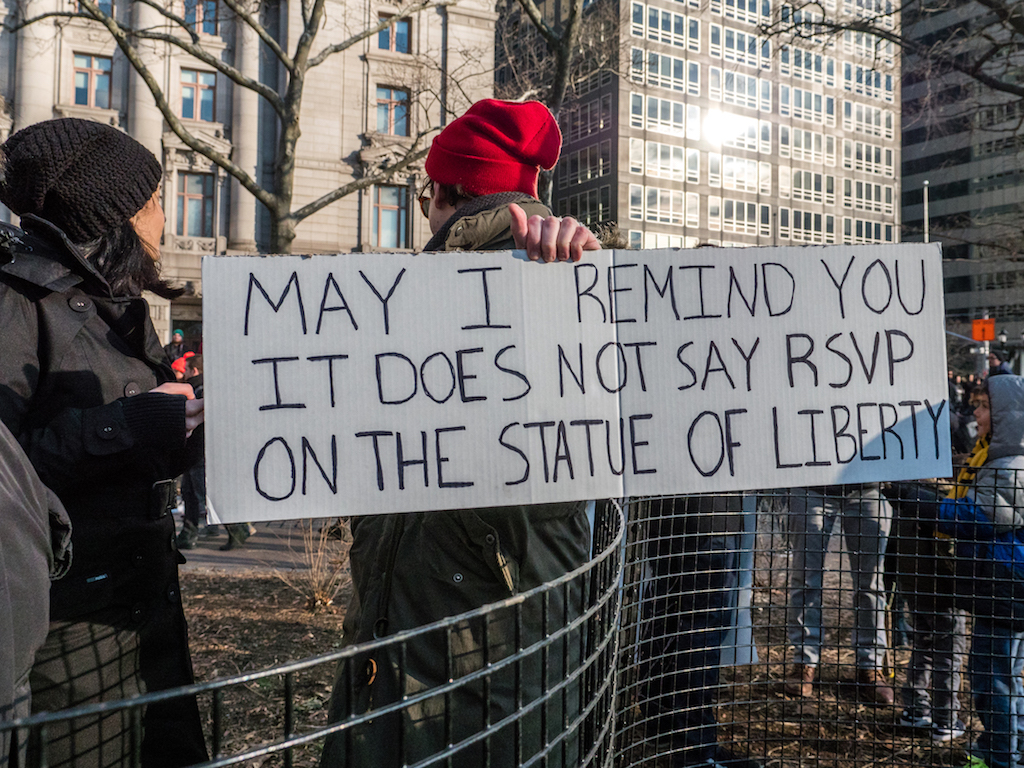

On the march up to Foley Square after the rally, the streets were filled with a sea of hand-drawn signs, nearly all participants bringing their own special message. One showed the Star of David, and read: “When we said ‘never again,’ I thought we meant ‘never again’”

A young woman (with her hair free and no hijab, contrary to the stereotype) held a sign reading: “I am a Muslim and I am not a terrorist.”

Nearby, a young man held a sign reading, “Jew not afraid of Muslims.”

An elderly man with a grim countenance watched from the sidewalk with a sign reading: “SOVIET REFUGEE FAMILY 1990”.

One placard showed an outline drawing of the Statue of Liberty, with the words “I’m with her.” Many signs quoted the text of the famous Emma Lazarus poem at the statue’s base.

A middle-aged woman held her sign up to the marchers from her sidewalk perch: “My Italian great-grandmother was aided by Syrian Americans in 1910 — paying it forward makes America great again!”

This story I needed to hear. The woman, Annmarie Zhati Agosta of New Brunswick, N.J., responded to my query.

“My great-grandmother came from Salerno at the turn of the century,” she said. “Her husband died on the boat, and she was pregnant. She was really desperate when she arrived here. The Syrian family that later opened the Damascus Bakery on Atlantic Ave. in Brooklyn gave her a job, cleaning house for them, and looked after her. They often sent her home with bags of groceries.”

Agosta said she remembered her grandmother and great-aunt, both born in Brooklyn, telling her how this generosity made a difference.

“They would talk about the Syrian pastries and the Syrian bread and all that,” she recalled. “My grandmother would wait in front of the house for my great-grandmother to come home with all the goodies form the Syrian bakery.”

They lived on Brooklyn’s Court St., not far from the bakery, which opened in 1930.

“What this country is about is helping each other and giving each other a leg up,” said Agosta. “Because sooner or later someone’s gonna turn around and do it for you.”

The day of the rally also happened to be the 95th birthday of Agosta’s great-aunt — the last remaining sibling of her grandmother — and she had just come from the party in Bensonhurst.

“I had to be here to honor my grandmother’s memory and the sacrifices she made for her family,” Agosta told me.

“Back then, Italians were the ones who were discriminated against,” she added, saying that the mafia stigma against her people was akin to the terrorist stigma that now attaches to Muslims. “If Trump were around back then, we wouldn’t have gotten in,” she said of her great-grandmother.

Agosta is today a Sufi Muslim herself, following the Nur Ashki Jerrahi order, which was founded some three centuries ago in Turkey but now has a dergah (Sufi meeting place) on West Broadway in Tribeca.

Up at Foley Square, I ran into a young man who looked more Latino than Germanic and held a sign reading: “My grandma didn’t survive Nazi Germany for this s—! (Sorry, Oma, for swearing)”

This was Tommy Van Cleave of New Rochelle. And indeed his oma (grandma) did grow up in Germany — in poverty during World War II, as her father had to flee the country to escape arrest for sheltering a Jewish friend.

“My grandma met my Mexican grandpa during reconstruction after the war,” he explained. “He had joined the Air Force to get U.S. citizenship, and was stationed in Germany.”

Van Cleave said he is now a professor of international studies, although he declined to name the school where he works.

“It would have been a betrayal of my grandmother’s memory for me to have benefitted from the welcome this country gave her, and not to protest now,” he said. “I have this life today because the doors were open then.”

A young Asian woman was holding a sign with a quote from Somali poet Warsan Shire: “You have to understand, that no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land…”

This was Stephanie Oula of Jackson Heights, Queens.

“We have to keep up the momentum,” she said when asked why she was there. “It’s only been one week, and it’s been a hell of a week.”

Oula is from a family of refugees.

“They came in waves from Laos, in the 1970s,” she said.

Southeast Asia was engulfed in war back then, but the atmosphere here in the U.S. was far more tolerant than today.

“The way my father talks about it, it was a very welcoming time,” she said. “If they had stayed in Laos, there’s a large possibility I wouldn’t exist.

“At the end of the day, that’s what this country is about,” said Oula, who works as a program officer at United Nations Foundation.

Now it is going on nearly two months since the inauguration, and we are going deeper into a notion of what the country is about, sharply at odds with the vision of many New Yorkers.