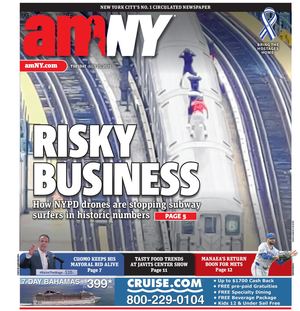

‘Club’ and ‘Project’ shine light on risk, rage

THE BANG BANG CLUB

Directed by Steven Silver.

106 minutes.

Available via Movies on Demand, through June 23. Use the zip code finder at www.tribecafilm.com/tribecafilm for all available options. NYC outlets include Time Warner channel 1,000 and Verizon FiOS.

REVIEW BY RANIA RICHARDSON

At TIME Magazine (where I worked in production during the 1990s), the combat photographers were rock stars. Were they as handsome as actor Ryan Phillippe? Oh, yes. Were the photo editors attractive like actress Malin Akerman, and romantically entangled with their charges? Absolutely. Did the reporters who sat behind desks all day live in envy of the men who could walk between bullets? You betcha. It’s no wonder “The Bang Bang Club” gets it right.

Director Steven Silver based the film on the memoir of two photojournalists and their experiences in South Africa, capturing turmoil in the final days of apartheid. What the film lacks in pacing and historical clarity, it makes up for in feel and inspiration. It evokes the thrilling cauldron of a photo department like the one I cross-trained in at TIME.

Philippe plays Greg Marinovich, who wrote the memoir with João Silva. Kevin Carter and Ken Oosterbroek round out the renegade band of photographers, fearless in their hunt for the quintessential image, taunting death as unofficial military embeds. Akerman depicts Robin Comley, picture editor for the Johannesburg “Star” — whose affair with Marinovich provides a counterpoint to prolonged battle scenes and mayhem.

Ethical questions are lightly woven throughout the story. Can white journalists understand the plight of black Africans? Should the lion’s share of reporting come from them? Is a photographer complicit in violence if he is emotionally detached from it? Is it exploitative to profit from the misery of others to get a news photo?

Carter, played by Taylor Kitsch, struggles with such accusations after winning a Pulitzer for a shot of a vulture stalking a Sudanese girl who he failed to help. A drug addict fueled by the adrenaline rush of combat photography, Carter had a tortured soul — but it enabled his quest for the truth.

Alex Hopkins, in Sioux City, Iowa (from “The Bully Project”).

THE BULLY PROJECT

Documentary. Directed by Lee Hirsch.

90 minutes.

Wed., Apr. 27, 7pm at AMC Loews Village 7 (66 Third Ave. at 11th St.). Sat., Apr. 30, 4pm at Clearview Cinemas Chelsea (260 W. 23rd St., btw. 7th & 8th Aves).

For tickets ($16), purchase at the Box Office or call 646-502-5296 or visit www.tribecafilm.com.

REVIEW BY TRAV S.D.

You’d have to have a heart of stone not to feel for the five families who struggle with the effects of schoolyard bullying. But while apparently inarguable and straightforward, Lee Hirsch’s documentary obscures a number of nagging questions.

To its credit, the film lets its subjects speak for themselves. A broad range of impacts are represented. Two of the families are recovering from the suicides of their sons who preferred to take their own lives rather than face another day of torture at school. One girl is facing 46 felony charges after she confronted her tormentors with her mother’s handgun. Another girl (and honors student and star athlete) has dropped out of school after suffering abuse from both teachers and students when she came out as a lesbian. And the fifth example shows the bullying in progress — a young boy with Asperger’s syndrome who gets picked on practically every moment of his life.

This last example is the most squirm-inducing, and highly impressive filmmaking. You have to wonder how the filmmakers got this footage of the wanton cruelty of children. Was the camera hidden, or were the kids just blithely, flagrantly monstrous, heedless of the consequences of being observed? Sadly, the latter scenario is all too plausible. It’s the pervasiveness of such cruelty that chills the blood.

The movie depicts not only the overt brutality of schoolmates, but the subtler meanness of parents, siblings, teachers, bus drivers and principals. If anything, the statistics the filmmakers give must lowball the extent of the problem.

Which leads me to one of my criticisms. The five stories the film examines all take place in the South and Midwest, and happened in rural areas and small towns (Sioux City is the biggest town represented). This might imply that the problem is unique to those regions. But, as we all know, the problem is universal. There is just as much of it, if not more, in the north and in urban areas. (The incident of the Rutgers freshman who killed himself after he was outed and humiliated via webcam springs to mind). And there are some omissions in the depth of the film’s probing. One of the kids (an eleven-year-old) killed himself with a gun. Another brought a gun to school. Had it gone off, she would have been a school shooter, crossing the line from victim to monster. Bullying is a subset of the larger problem of human violence, which extends far beyond the school grounds.

Contrary to what the film seems to imply, it will take far more than a “Stop Bullying” campaign to stop bullying — it will take a miraculous revolution in every human heart. But the film awakens us to one finite manifestation of the problem, and awakens our sympathy and concern. That’s a start.