BY YANNIC RACK | Student workers at New York University will soon make $15 an hour, after the school’s new president announced he would raise their minimum wage over the next three years, ending a yearlong campaign by activists who demanded better pay at the country’s third-most expensive college.

Andrew Hamilton, who took over the reins at the school in January, wrote in a memo to students and faculty last week that the pay raise would be implemented starting this year.

“The topic that recurs most often in my meetings with students is affordability,” Hamilton wrote on Thurs., Mar. 24. “As I have listened to students in various settings, I have repeatedly heard that raising the minimum hourly rate we pay to student workers is an important way to reduce the burden on families and to ease the pressure that students sometimes feel, even when they are getting generous scholarship aid.”

The increase will be incremental, with a new minimum hourly rate of $12 for 2016-17, a minimum of $13.50 for 2017-18, and a final raise to $15 an hour for 2018-19, according to the university.

The announcement, which comes as Governor Andrew Cuomo is pushing for a $15 minimum wage across New York State and the “Fight for 15” movement is gaining momentum nationwide, was followed by Columbia University announcing its own wage increase less than a week later.

Students at N.Y.U., who say they were previously paid as little as $9 an hour, praised the school’s move but remained skeptical about their new leader’s intentions.

“It’s the result of a long student-led campaign on campus, and so we’re very excited that N.Y.U. is taking this step forward,” said Katie Shane, a junior and a member of the local chapter of the national organization United Students Against Sweatshops. “But it’s still up in the air whether this is a trend or just a one-time decision,” she added.

Hamilton, who spent the last six years as vice chancellor of Oxford University, succeeded John Sexton, whose billion-dollar “N.Y.U. 2031” expansion plan in Greenwich Village alienated large groups of local residents and faculty members before his 13-year tenure ended last year.

Despite scoring points for the minimum-wage announcement, Shane said that other issues around fair education at the school remain under Hamilton.

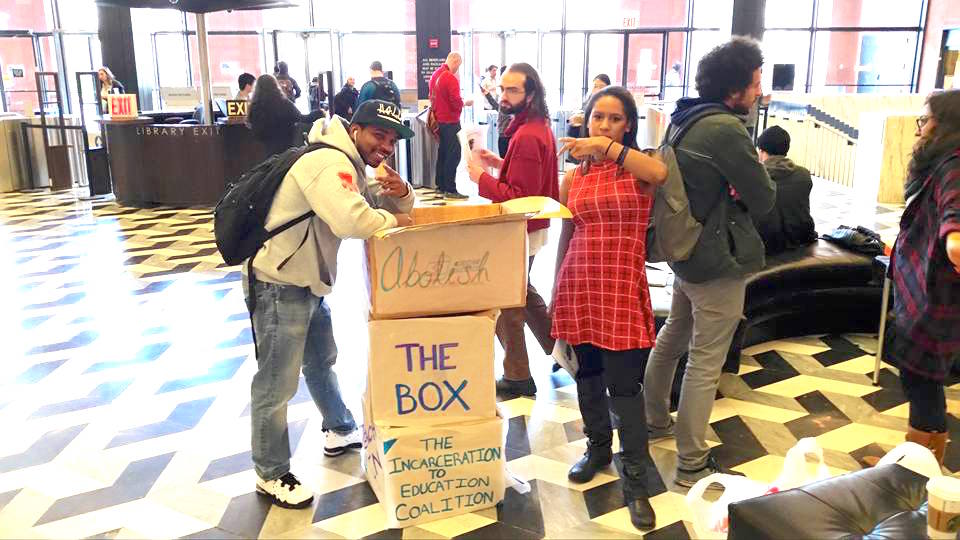

She was one of a few dozen students who took part in a 30-hour occupation of the university’s Kimmel Center last weekend, for example, in a protest over N.Y.U.’s continued use of “the box” — which formerly incarcerated applicants must check — on its school applications.

SLAM organizers praised the minimum-wage announcement last week, saying the move would make the university the first private school in the group’s network to raise all workers’ minimum hourly pay to $15 across campus — but they have even more to celebrate this week, after Columbia announced it would follow suit.

The school’s provost told students in an e-mail on Monday that the university “will be raising the pay rate of all part-time hourly student workers to $15 per hour over the next three years” — leading some N.Y.U. students to speculate on the impact of Hamilton’s announcement and their own campaigning.

“It sort of shows the infective aspect of this Fight for 15 movement going on across the country, and across the state particularly,” said Drew Weber, another SLAM member and N.Y.U. junior, after learning about the news.

“There’s been a lot of pressure from us and from the state, and I think the two sort of fed into each other to bring us here,” he said.

The minimum-wage campaign at Columbia was led by a group called Student-Worker Solidarity, another U.S.A.S. chapter, and the organization noted that similar efforts are currently also underway at Macalester College, as well as public universities, including the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Students at N.Y.U., whose debt after graduation runs about $35,000 on average — but can go much higher — are hopeful the raise will have a big impact.

“As a student worker, $15 isn’t just a rhetorical number for me,” said Hannah Fullerton, another student at the university. “I’m set to graduate with $80,000 in student-loan debt. In the past, it’s been nearly impossible to work enough hours to earn my entire work-study award. This will put a dent in my living expenses, and in the debt I’m already accruing.”

When adding up average tuition and fees, plus room and board, it costs more than $65,000 a year to attend the school.

Hamilton emphasized that the university already saw the lowest increase in attendance costs in 20 years for the next academic year, which is set to see a 2 percent hike, and that a steering committee is looking at “additional ways beyond that first step to reduce the cost of N.Y.U. education for students and their families.”

The N.Y.U. president also said the pay raise would especially benefit those students that already rely on financial assistance through the university’s work-study program, a mix of financial aid and compensation.

“Work-study is another important way that students help pay for college,” Hamilton wrote, “and also pay for the experiences that accompany a college education: sharing a meal out with friends, attending the cultural events for which New York is duly famous, or simply addressing the myriad expenses that come with being on one’s own at college.”

All of N.Y.U.’s full-time employees and graduate student workers, as well as full-time employees of on-campus vendors, already receive at least $15 per hour, according to the university.

The move also comes as Governor Cuomo aims to increase the minimum wage to $15 an hour statewide — and Hamilton emphasized that he would stick by his plan no matter what lawmakers in Albany decide.

“Even if there is no agreement on this issue, or if the agreement calls for a longer time frame, N.Y.U. will move forward with its plans,” he said. “And, of course, should state legislation call for a quicker time frame, we will comply with that.”