By Julie Shapiro

Over its 200-year history, Castle Williams has been a military fortress, a prison for Confederate soldiers, a pig grazing pen and a teen center.

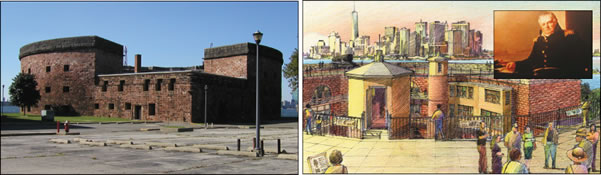

Now, the National Park Service hopes to turn the red sandstone fort on Governors Island into a museum. The full plans will take 20 years and $60 million to realize, but the N.P.S. recently started cleaning and stabilizing the three-story, doughnut-shaped building using a $6.4 million federal grant.

“Every layer of its use — as a fort, a barracks, a prison, a daycare center — every layer of that right now is still there,” said Michael Shaver, chief ranger on Governors Island with the N.P.S. “We’re just going to clean the tarnish off those layers so you can still make them out.”

Most recently, Castle Williams, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, has become a daytrip destination. Drawn to the weathered facade and ghostly, crumbling courtyard, about 50,000 tourists and history aficionados visited the castle last year, according to the N.P.S.

“It’s just weird and funky and very inviting,” Shaver said. “You see it on the ferry coming over here and it’s one of those things you want to check out.”

Castle Williams will be closed this summer because of the restoration work, which includes asbestos and lead abatement. When it reopens in May 2011, visitors will be able to explore not just the fort’s round courtyard but also the roof and some of the interior, which have never been open to the public.

The roof will offer sweeping views of New York Harbor, and a glimpse back in time at the impregnable defenses that protected the city for decades. Castle Williams, together with Fort Jay on Governors Island, Castle Clinton at the tip of Manhattan and forts on Ellis Island and Liberty Island, made an imposing impression on any would-be attackers, convincing the British not to enter the harbor during the War of 1812, Shaver said.

While the rectangular Fort Jay was more traditional, Castle Williams was designed to make an impression. Shaver likened it to a fist.

“It’s not a fort that’s [only] trying to protect itself,” Shaver said. “It’s a projection of strength out in New York Harbor that’s just daring people to come.”

Castle Williams was the brainchild of Col. Jonathan Williams, chief engineer for the U.S. Army and superintendent of West Point — and also, Shaver said, “a fort geek.” Williams traveled to France studying the forts, then returned to the United States in 1785 determined to reinterpret them in a modern way.

Castle Williams, which opened in 1811, was the physical expression of Williams’ pioneering ideas. While most forts were rectangular, Castle Williams was round, to provide full coverage of the harbor. And while other forts propped canons on top of walls, opening them to opposing fire, Williams stacked his cannons vertically, sheltering them in stone casements, with walls 7 to 9 feet thick.

When Williams was designing his fort at the beginning of the 19th century, protecting New York City was an urgent task. Thirty years earlier, the British sailed into New York’s largely defenseless harbor during the Revolutionary War. The British used New York for their headquarters for eight years and did not leave until Evacuation Day in 1783.

After the war, the fledgling American government prioritized the security of its financial capital, building more than a dozen protective forts. Castle Williams was one of them.

The defenses came in handy during the War of 1812, when the British laid siege to New York Harbor but never tried to enter or attack Manhattan.

“They didn’t mess with the city like they’d done before,” Shaver said. “With all these forts working together, there was no way any reasonable man would try to do a naval invasion of New York. It just was not going to happen.”

In fact, Castle Williams was only attacked once, and it was by Williams’ friends at the U.S. Navy. Williams was so proud of his design and eager to prove its strength that he invited the Navy in to test the fort’s defenses. Williams, the great-nephew of Benjamin Franklin, stayed in the castle while it was under fire. No one was hurt, and the Navy managed only to knock over one of the fort’s cannons, but not to destroy it.

Only one portrait survives of Williams, and it shows the castle in the background. Castle Williams is also imprinted on the buttons of the dress uniforms of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in tribute to Williams.

During the Civil War, the mission of Castle Williams shifted from military fort to military prison, for both Confederate soldiers and Union deserters. In the century after the war ended, the federal government continually updated the prison to make it more modern and secure, adding the steel bars that are there today.

The U.S. Coast Guard took over Governors Island in 1966 and initially planned to tear down Castle Williams but decided to convert it into a community center instead. The cells that once housed prisoners soon held woodworking classes, boy scouts meetings, a radio club, a photography lab and a daycare center. Later, the Coast Guard used the castle as storage for landscaping equipment like lawnmowers.

After the Coast Guard left the island in 1996, Castle Clinton sat empty and open to the elements. The National Park Service’s takeover of the castle and other historic parts of the island renewed interest in restoring Castle Clinton, and it has fascinated thousands of visitors since the island reopened to the public in 2003.

In the long term, Patti Reilly, superintendent of Governors Island National Monument, wants the castle to become an interpretive Harbor and History Center, where visitors can learn about not just the fort’s prior life but also about the preservation of the waterfront as a whole.

In addition to opening the roof to the public, the only part of the project that has funding so far is the first phase, which will secure the structure and rid it of hazardous materials. The $6.4 million grant, from the federal stimulus package and U.S. Rep. Jerrold Nadler, will allow visitors to explore previously closed-off parts of the castle starting in 2011 but will not be enough to build the full museum and center, Reilly said.

Shaver is optimistic that the rest of the funding will fall into place.

“We’ve just got to clean it up so people can get into it,” he said. “Once you can go in and you can love it and hug it, things will come in easier.”

Julie@DowntownExpress.com