BY TIM GAY | It was a cold night in early March 1992 when Bill Cullum found my number and called me. Like a shady lady from an old Dashiell Hammett mystery, Bill was a young man in danger. Bill was being harassed and about to be illegally evicted from an illegal living space in a basement by an evil lesbian who happened to be my next-door neighbor.

To make it more complicated, the illegal basement was in my building, and the basement was a portion of an apartment that had belonged to a man who drank himself to death two weeks earlier. The man hadn’t paid his monthly maintenance since 1987 (he drank on the money Bill paid); so technically the apartment should have reverted back to our radical-feminist-lesbian-gay-terrorist-co-op. But the evil lesbian had somehow convinced the Surrogate Court probate judge that she was the “administrator” of the dead man’s non-estate. Everyone in our co-op knew that the lesbian lusted to move into that 1,200-square-foot, quasi-legal apartment.

This was rather normal at the time in Chelsea, when everyone knew our neighbors. Each Gay Pride, Jerry Scarano of W. 19th St. would berate gay, straight and bi store owners for money so he could buy and hang rainbow flags (without permits) on lampposts from 14th to 23rd Sts. Pat Rogers and Bob Barbero whisked away their tablecloths and transformed their high-tone restaurant into Food Bar.

Tom Duane of 16th St. had just taken the oath of office as our first gay city councilmember. Deborah Glick, below 14th St., was entering her second year in the Assembly.

Sex workers colorfully performed their jobs west of Ninth Ave. The gay men in leather were getting older while young lesbians and gay men embraced “queer” and wore construction boots and cutoffs. A Different Light Bookstore moved up to 20th St., and the Chelsea Gym unofficially provided discount memberships to our “poz” brothers.

It turned out Bill and I knew a lot of people in common. We both worked for the New York Native newspaper and Christopher St. magazine. Bill was the staff photographer. I was a freelance writer. We both knew a number of ’70s and ’80s gay activists, including Ethan Ghetto, Frank Salonno, Ed Rogowski and editor Brett Averill.

But we never met until 1992.

Although I am only three years older, we were of two different generations. As Bill later told me, “You are Stonewall. You moved here in 1980, and got involved with the Gay Activist Alliance crowd, the gay intelligentsia, radical faeries and liberal theologians.” It was true that I hung around the waterfront bars and clubs and the Mineshaft, and was an AIDS widower in 1984. But then I got respectable, found a rich boyfriend, wore Brooks Brothers suits, became a community activist and joined the political establishment.

Bill was the next generation.

“I came to New York in 1978 with a boyfriend and hung around Studio 54,” he said. “I left and came back in 1981 with a new boyfriend. He was getting his M.B.A. at Stern and I was going to SVA. We stumbled on Rounds, the hustler bar on the East Side, one night. We looked at each other and one of us said, ‘This is how we’re going to pay our tuition.’ And we became call boys.”

Bill hung out with the White Columns art crowd and lived first in Hells Kitchen and then on E. 14th St. Bill served the rich and famous not only as a sex worker but a confidant. As he said, “Men pay you to listen, or men pay you to leave.” He had sex with the rich and famous, and later delighted me with details of his three-way with the Canadian hockey star and his wife, whom he met at the Hellfire Club.

And Bill certainly had a political sensibility. He was “introduced” to Roy Cohn and accepted Roy’s invitation to a private dinner for the two of them at Norman Mailer’s house on Cape Cod. After dinner, Bill declined Roy’s sexual advances.

Bill became a “post-modern” artist and had several shows at Deb’s Gallery. He was featured in Art in America.

Although he tested positive for H.I.V. in 1986, Bill was never in ACT UP. Still, he found himself as a national AIDS role model. Because he was the administrative assistant for Dr. Joseph Sonnabend of CRIA (Community Research Inititative on AIDS), he was booked reluctantly as the “human-interest guest” on CNN and the major network news programs. MTV shot a short video for the first World AIDS Day starring Bill and his Bide-a-Wee rescue dog, Caliban. On his left deltoid, Bill sported a black cross tattoo with “HIV+” in the middle.

We ran into each other throughout the ’90s. Then in the early part of this century, I didn’t see him around as much. I tried calling him in 2003 to tell him the evil lesbian had a brain aneurism and died. But he didn’t return my calls.

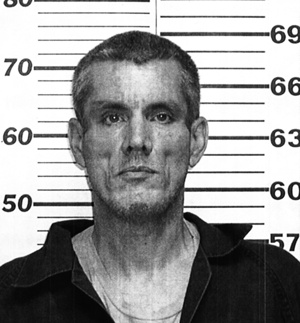

His ex-lover told me Bill was on crystal. Then I saw Bill was on the cover of Gay City News, having been arrested as a crystal dealer. The Bush-era Drug Enforcement Agency propped Bill in front of a camera and used him as a crystal meth poster child in full-length bus stop advertisements on Eighth Ave. This hysteria was short-lived as a judge ordered the posters removed.

Then Bill was sent to federal detention in Brooklyn, where John Gotti’s brother one morning yelled out “BILL! YO IS FAMOUS! CHECK OUT DA PAPER!” as he pointed out the front page of the Daily News. And then Bill was sent to prison, first to North Carolina (to be closer to his family and smuggled cigarettes) and then ending up in the medium-security prison camp at Lewisburg, Penn.

During his six years away, my ex, Phil Ryan (who knew one of Bill’s exes; it is a small world after all), would send Bill subscriptions to The New York Times, The Economist, books and some extra money so Bill could buy packaged mackerel from the commissary.

The mackerel became currency.

“If you had more than 49 mackerels, you were a mackerel-aire,” Bill noted.

And Bill took up art in prison. Friends sent Bill art supplies. Bill would paint post-modern portraits of the foil packages of mackerel, which he would then sell to the white-collar criminals when they were finally leaving the prison.

I traveled with Phil twice to visit Bill in prison. He was no longer the early-30s-something pretty man, but was middle-aged, and his hair had turned a beautiful silver. He still had the troublemaking, baby blue boy eyes and smile. Most apparent to me was how mellow Bill was about his whole experience there, sort of existential, like The Stranger, but with a certain warmth and humanism and humor.

Bill and Phil and I had long long talks from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m., as the children and families visited with their men. Bill described the social dynamics of the medium-security camps as basically coming down to two camps: the mostly white, financial and political criminals (many of whom, Bill said, were unrepentant), and the African-American and Hispanic men who sold or used drugs. Occasionally, there was the gay man convicted of either drugs or money crimes.

Bill was once asked by the warden to look out for a pre-op, male-to-female, transgender woman who was still classified by the feds as a man. And Bill did exactly that. Bill said he identified much more with the black and Hispanic men than he did with the white men. Bill was outed by a guard for being H.I.V. positive and gay, but in a testament to modern times, his fellow prisoners didn’t care.

Making his way back toward freedom, in the summer of 2010, Bill was at a halfway house in the Bronx, along with some 300 federal prisoners. Conditions were deplorable. Bill could not reinstate his Social Security. There were waiting lists at the AIDS supportive-housing places. Bill’s city Department of Health HASA caseworker in the Bronx was problematic.

“If I had known it would be like this, I would have stayed in prison to finish my sentence,” Bill told me.

Then he found out he could stay with a relative or friend. His federal release officer suggested that even a sofa would be considered a home. So I said, “Why don’t you stay with me until something opens up at Flemister House, or Harmony House?” And Bill accepted.

First came the site visits by the Department of Justice Federal Release officers. Then came the visit from the social worker from the city. Then I had to send proof that the rent and utilities was paid. And then Bill moved in.

After two decades, Bill returned to 300 W. 17th St., rising from the basement to the sixth floor with views of Times Square and the Empire State Building.

No, it wasn’t easy at first. All my friends raised eyebrows. My therapist expressed deep concern. And Bill’s transition was gradual, with small steps. At anytime day or night the phone would ring. Bill would answer and give a certain code. For the first several months, he had to plan and receive permission for his trips to the doctor.

Then, things started to normalize for Bill and me. No one had lived with me since 1999. Bill tamed my wild kitchen and asked me to buy proper knives and skillets. He eventually persuaded me to buy a new stove. He began cooking again (he studied French cooking and was the manager for Mariel Hemingway’s restaurant Sam in the late ’80s) and started making me real food. He reorganized and cleaned my small, loft-like space. Bill transformed his side of the space into a an artists studio.

Then there were the firsts in freedom — the night I brought home a porterhouse steak, and he handmade a Béarnaise sauce; the look on his face when he bit into a fresh strawberry and tasted real whipped cream again; the joy of freshly ground and brewed coffee; actually shopping for groceries and buying fine mustard and real ice cream.

While he was still under house arrest, a group of men started a Crystal Meth Anonymous meeting in my apartment every Tuesday at 7 p.m. — because they wanted to support Bill, and Bill could not leave to go to a meeting.

I would come home from working 12-hour days at the election board, and there would be a group of guys, all in recovery. For the first time in years, I was meeting a new group of gay men who were addicted to something I never quite experienced.

The home phone started ringing again. We were getting calls not only from his federal officer and social worker, but from other guys, all for social and recovery calls.

When Bill’s exile on Eighth Ave. ended, he started going out, slowly at first, to the galleries and to recovery meetings. Bill then helped found the first Crystal Meth Anonymous meeting Uptown in Harlem, because not all meth addicts are white gay men in Chelsea.

And he began painting again — portraits of foil packages of mackerel, unusual art featuring the Vietnam-era monk who burned himself to death, and orchids, and items I don’t understand.

And everyone says the food at my annual Thanksgiving dinner has never been better. Last year Bill took over the kitchen and the new stove and told me to entertain the 20 guests. We’ve gone through two holiday seasons together.

Most important, I am amazed there truly still is a supportive community of men out there. Bill gives help and gets helped when he’s in times of need. Together and individually, we’ve stayed up late, talking to guys coming off or staying away from crystal or booze or cocaine. I’m seeing a new group of young men who are H.I.V. positive, and I’m finding I can be helpful too.

Last year, Bill befriended a 24-year-old man with full-blown AIDS and we adopted him. We called him our feral son, because David was one of those kids pushed out by his parents because he was gay. David stopped living at home when he was 12. I think we helped him in that transition to manhood — and that’s another story.

Bill’s an atheist and has absolutely no regret for his past — as a sex worker, drug addict, small-time dealer. Sometimes he jokes that, “We’re doing the Lord’s work.”

Because of Bill, I’m exploring my old spiritual roots. Bill thinks there’s an inner Radical Faerie in me, and I think he may be right. Eventually, Bill will leave, but I keep half-jokingly begging him to stay — at least until after the presidential election.

And Bill is writing his memoir, titled, “Slouching Toward the Big House.” But that, too, is another story — Bill’s story.