By Harry Newman

Kameron Steele first saw Terayama Shuji’s avant-garde classic film, “Den’en ni Shisu (Death in the Fields),” in Tokyo in 1991, where he had gone to continue his education in theater after graduating Northwestern University. He had only been in Japan a year or so and wasn’t able to follow everything. “But I was fascinated by the images and characters and the story,” he recalled, “the odyssey-like quality of it.”

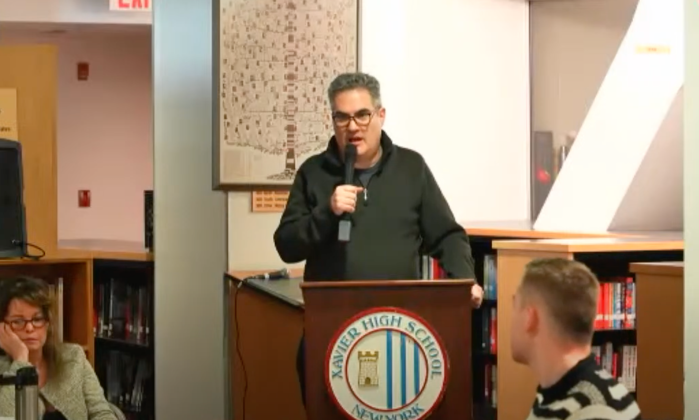

Now, fifteen years later, Steele is premiering his stage version of the film, “Death in Vacant Lot!” this month in New York. Created with his performance company, The South Wing, from his own adaptation and translation, the production is finishing a two-week run this week at Swing Space, the Lower Manhattan Culture Council’s recently opened performance space in the Financial District. This is the first showing of Terayama’s work in New York since the 1970s and the first time permission has been given from the Terayama estate to adapt any of his work.

In those fifteen years, Steele undertook an odyssey of his own. Shortly after coming to Japan, he began acting in renowned director Tadashi Suzuki’s SCOT theater company, eventually becoming his assistant director. He went on to become an internationally recognized teacher of Suzuki’s theater methods — a rigorous set of physical and vocal exercises to ground the performer in the body, leading to more intense and deeper emotional expression. He later spent five years performing with theater visionary Robert Wilson. In all that time, Terayama’s film stayed with him.

“What kept me attracted was the autobiographical nature of it,” he said at the theater just before a weekend performance. “And the fact that it articulated a very difficult moment in history and asks how you deal with memory, how you deal with your culture, your heritage when you don’t necessarily agree with it.”

Terayama Shuji was a leading figure of the Japanese experimental theater and film of the 60s and 70s. “Death in the Fields,” which was shown at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival, is one of his last and best-known works. Drawn from his tragic experiences as a child in the immediate post-World War II era, the film follows a 16-year-old boy who runs away from his isolated rural town and later returns as a man to look for his twenty-year-younger self.

Adapting any film to the stage is hard enough, let alone an experimental film — in Japanese, no less — whose narrative is presented through fragments of short scenes, images, music and tanka poetry. The answer for Kameron Steele is the Suzuki training which provides the actors with a level of physicality that allows for great flexibility and fluidity. The body (or groups of bodies) becomes the basis for discovering equivalents to the unique elements of the film. All the performers in the production are trained in Suzuki and were chosen by Steele from workshops he has conducted. They achieve a remarkable level of physical unity and cohesion — all clearly sharing the same imaginary world — while at the same time moving in and out of some 40 individual roles.

The end result is an engaging, kaleidoscopic memory play of startling images, unexpected humor, and surprising tenderness. An actor, poised on the back of another performer, becomes a baby grasping its umbilical cord as it tries to stay in the womb as long as possible, while her mother in labor prays for a healthy child. A circus comes to life whose central figures are an inflatable lady (poignantly played by Jessica Green), who seems to float in air before your eyes, and her midget husband portrayed with amazing inventiveness and yogic suppleness by Gillian Chadsey. A seduction, performed by Nate Schenkkan and Catherine Friesen, becomes a literal battle of the sexes. Throughout, characters and scenes transform almost instantaneously. It’s a wonderfully controlled, open-ended chaos with multiple potential meanings.

“Theater for me is a kind of poetry, not just in presentation, but its associative possibilities,” Steele says when asked about a certain image. “I try not to give answers in my plays.”