BY MINERVA DURHAM | For years I was curious about the four sisters of Matthew McGuigan, the redheaded Irish super at 226 Lafayette St. in Soho. Were they graceful and charming, I wondered? Redheads, like him? Did they have, in the words of Thackeray, “something better than beauty?” Matthew also had two brothers, but I didn’t wonder about them.

Matthew’s parents met in America, each one having come here alone, his father from County Tyrone and his mother from County Wexford. They married, worked and brought up their seven children in extreme poverty in the housing projects near the 59th St. Bridge on the Queens side. Not until their youngest son, Patrick, got a job with TWA did the family move out of the projects.

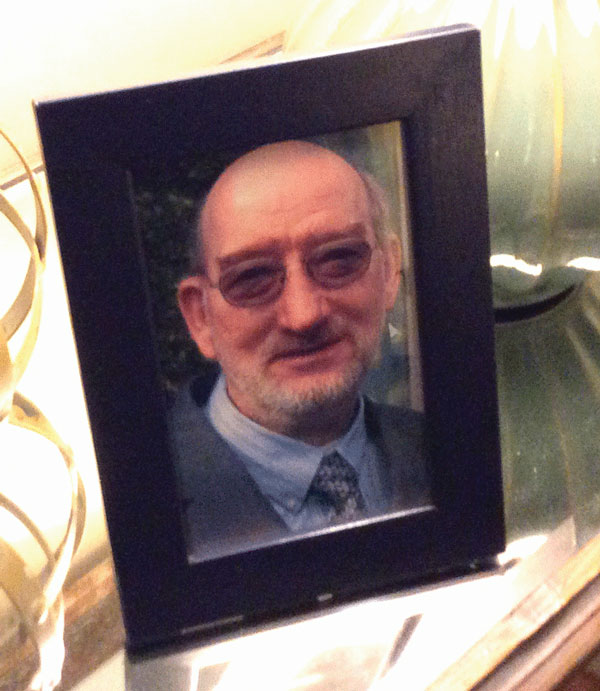

Matthew, the middle brother, was one-of-a-kind. He could fix anything. He couldn’t read or write well, so his sisters would write up invoices, fill out forms and compose letters for him. One sister spoke on the phone with him on the same day of the week and at the same hour every week, like a clock.

His siblings seemed to have a protective attitude toward him, perhaps because he was a premature baby, weighing only one pound at birth, according to one of his sisters. Not even the doctors thought he would live.

As an adult he was handy, solitary, self-sufficient, good-natured and seemingly incapable of ever harming anyone or of ever even suspecting that anyone might harm him.

Matthew died on March 8 at age 66. His wake at the Romanelli Funeral Home on Rockaway Boulevard in Ozone Park on March 13 was the sad occasion that allowed me to meet three of his sisters. Noor (she changed her name from Catherine) flew from Holland where she has lived for 40 years. Sheila and Joanne flew from Texas where they have lived for most of their adult lives. The oldest sister, Mary, also a resident of Texas, could not attend, but her daughter and granddaughter were there.

I met Noor first. She spoke with a keen spark of wit. Her face resembled Matthew’s. Her complexion and hair were somewhat ruddy, her body agile and athletic. She was not the oldest sister, but she seemed to be the dominant sister, the one who kept everyone in line and made sure that things got done. Matthew had visited her in Holland a few years earlier, and on the second day of his visit he had suggested that he might re-hang the doors in her house. They were badly aligned, he said.

So eager was she to have the doors fixed, and so hoping not to jinx the project, she hid her excitement from Matthew until the job was all done and the doors opened and closed properly.

Joanna’s face had the sort of beauty that many people might miss. It was made up of ideal medieval forms, a good strong chin, very thin and shapely lips, a long thin nose, kind eyes and a tall forehead. A special-education teacher, Joanna had an air of exhaustion and disappointment about her, perhaps just an expression of her deep grief. Matthew was a year older than Joanna, and he was especially close to her. Before he got sick, he had been planning to retire to Texas and live near her.

The baby sister, Sheila, moved gracefully and dressed glamorously. She admitted to bleaching her hair. She was the adventurous one. The first sister to go to Texas, she had accepted a job there on the spur of the moment and never returned to live in New York. She married a Chinese man. Her grown son was proof of the union. His eyes were Asian, but his bushy black beard and tall, muscular body suggested that his Irish genes had overpowered others.

Everyone was waiting for Owen, the firstborn of the seven siblings. I was warned that he might say something unusual and playful and perhaps shocking. Indeed when he met Sandy Rheingold, a plumber who had worked with Matthew in Soho for nearly 40 years, Owen asked Sandy, “Are you dandy?” Then he turned to me and said that he admired my name. I must be a goddess, he said, or maybe a witch.

Owen was a storyteller, right away mentioning that Matthew worked for Bob De Niro Sr., the father of the famous actor, saying that they had met on 35th St. when Bob lived there. Like most old stories, Owen’s had some facts reversed, some details distorted and important parts left out. Matthew had worked first, not for Bob De Niro Sr., but for Bob’s ex-wife, Virginia Admiral, at 226 Lafayette, and he continued to work there after Virginia’s death in 2000 until he was too sick to work anymore.

Patrick reversed the facts of his story, too. He told us about Matthew’s vivid memory of the thrill of seeing Virginia’s famous son exiting a helicopter in Montauk with his girlfriend. But I was there with Matthew and Virginia on that trip in 1989, and we had watched the couple boarding, not exiting the helicopter.

Matthew, Virginia and I went to Montauk together for a week because Virginia needed Matthew to do repairs on the house there and she wanted me to do the cooking. We boarded at the W. 30th St. shoreline heliport on the West Side and had a short, glorious trip to Montauk. After we exited the chopper, we watched the famous couple run under its spinning blades, climb up and board it, and ascend in it as it flew to Manhattan.

At that moment Matthew and I were onlookers, sharing our worker status on the sidelines, outside of the circle of fame and glamour that Virginia’s son lived in. Don’t think, though, that we were unhappy with our lot. When we were with Virginia, we were part of the community that she had helped to create while she turned four cast-iron buildings into artist live/work cooperatives.

Early on, most of the artists who moved into Soho did the plumbing, carpentry and electrical work in their own lofts, hopefully overseen by licensed workers. Many took jobs constructing other artists’ lofts. They saw themselves as workers participating in an artistic revolution with socialist underpinnings.

Virginia had been an anarchist, pacifist and communist in Berkeley when she was young. In New York she followed the social ideas of George Maciunas, a Lithuanian-born Fluxus artist who sought to create a community of artist co-ops and to destroy High Art and bourgeois culture by displacing Art with everyday activities.

Everyone became equal during the growth of Soho, including Matthew McGuigan. He was respected as a craftsman and enjoyed easy social exchanges with everyone. The super of 226 Lafayette for almost four decades, he was a Soho treasure.

Patrick had grown to be the tallest McGuigan sibling and the one to assume the role of protector. It was he who stayed in constant touch with Matthew’s friends and employers throughout his illness. It was he who greeted everyone at the wake. After he made sure that Owen had met Matthew’s friends, it was time for the deacon to speak.

The deacon was dressed in a long, white tunic, a little tight around the waist. Despite the fact that he had never met Matthew, the deacon pleased the mourners with his humor and warmth. As he led us in prayer responses, the room was as one being, with one voice and one thought, solid and solemn, saying goodbye to Matthew.

Zaire Schoenholt, an owner of Spring Street Natural restaurant, arrived late, at nearly 5 p.m., just as the wake was ending. While Zaire sat weeping, Noor stood next to Matthew’s open coffin and read a poem. Then Noor invited all of us to touch Matthew, whose hands were wrapped in a rosary. It was our last chance to grasp his hands, kiss his face and say a final goodbye, Noor said.

Sandy, Zaire and I returned to Manhattan driven by Robert Haisley in his old Honda Civic. Robert and I had visited Matthew after his operation for brain tumors last September. An artist, architect and carpenter, Robert, like Matthew, could fix anything. For years the two had shared information as well as tools.

While we were stuck in slow traffic on the Williamsburg Bridge, Zaire asked Sandy, “Do you have any children?”

“Impudent,” I thought, but the loss felt at someone’s death makes people do and say funny things. Sandy answered the question. “Yes. I have one grown son.”

Six-year-old Etan Patz had disappeared when Sandy’s son was young, so we talked about the recent developments in the famous Soho case, until Zaire described a movie she had watched the night before when she couldn’t sleep. The movie was about a poor woman with many children who had fixed up a house in the Southwest.

During the telling, it dawned on me that Zaire’s story was not interesting. I began to tell her, “That movie is so boring,” but I began to laugh midsentence and I couldn’t speak at all for laughing so hard. I kept trying to speak until tears filled my eyes and then all the grief in me spilled out and I began to cry.

“Oh mean and angry God,” I wailed silently. “Why have you taken him? An innocent, too young, too good, too kind.

No sooner did I accuse my God than a voice swelled up inside my head. “Just who do you think you are, Old Lady? Who are you to question me?” the voice boomed. “Have you forgotten your catechism? Tell me, Old Lady, why did I make you?

“Now,” the voice became soft, “in answer to your questions, I made sure that my own son suffered as much as any human could suffer. I betrayed him and humiliated him. His suffering is an example to all humanity that everyone will suffer. It’s a lesson, a warning and a promise.

“About Matthew McGuigan. I need him here in heaven more than you artists in Soho need him on earth. The gates of heaven need alignment. He will know how to re-hang them.”

The Honda Civic, drunk with grief, rocked over the bridge and up Delancey, turned right onto Centre St., and stopped at Spring St. where Robert left us off. We kissed each others’ cheeks, tasting the salt of each others’ tears. …

In a postscript, Sheila reported that the funeral Mass was beautiful. Matthew had served in the Army, and at the end of the service, his coffin was draped with the American flag, which was then folded and presented to his brother Patrick.