By WILL McKINLEY

Dozens of Mets legends were honored at Shea Stadium’s closing ceremony last month, from Tom Seaver to Mike Piazza and all the lesser lights in between. But one seminal figure in the team’s history was conspicuous by his absence.

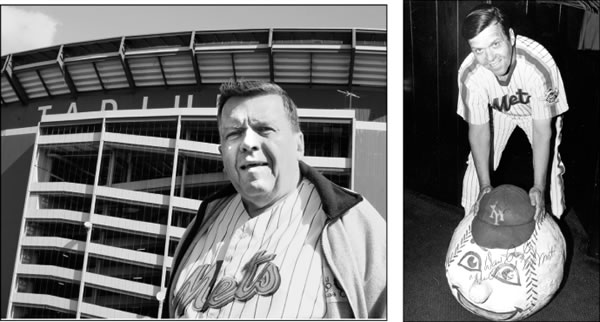

Dan Reilly, the first man to wear the costume of iconic mascot Mr. Met, watched the bittersweet festivities at home on TV like an ordinary fan. But the longtime Soho resident and author of the new book “The Original Mr. Met Remembers,” is anything but.

“I’m disappointed they didn’t invite me back, but I’m not angry,” said Reilly, who played the Mets mascot on and off the field from 1964 through 1967, the first three of his nine years with the club. “Seaver, Koosman, Swoboda, all those guys were my buddies. And I figured they’d like to see me again, too, just to say hello, a few handshakes, keep in touch. They all still call me Mr. Met.”

Now 70 and retired, Reilly’s ties with the team go back to Shea’s inaugural season, when he joined the Mets ticket sales staff two months before the debut of their new home.

“It was a snowy February morning the day of my interview,” Reilly said last week, as he walked the grounds of the soon-to-be-demolished stadium. “From the outside, it looked like an orange-and-blue skeleton. Nothing was happening and nobody was around. Inside, they were still putting the seats in. And now I’m watching them take those seats out. It’s sad.”

Sadness is not an emotion readily associated with Reilly, a jovial, outgoing raconteur who worked in the restaurant business after leaving the Mets in 1972, and recently concluded a four-year stint as the host of game-day ferry rides to Shea. On boat or barstool, the Richmond Hill, Queens, native spins colorful tales of the early days of the Amazin’ Mets with a hearty laugh and, on this occasion, a misty eye.

“We were a small organization back then, no superstars,” said Reilly, clad in a Mets jersey and still using “we” and “us” when referring to the team he left 36 years ago. “I drank with those guys. I knew where all the good Irish bars in Queens were. And I knew when to keep my mouth shut. That’s why everyone liked me.”

Reilly was front and center for nearly all of the significant events of the team’s first decade: Shea’s first opening day; the 1964 All-Star Game; Casey Stengel’s on-field 75th birthday celebration and the infamous after-party at Toots Shor’s, where the legendary manager broke his hip and ended his career; the arrival of 1967 Rookie of the Year Seaver; the managerial tenure of Reilly’s boyhood idol Gil Hodges and, most memorably, the Miracle Mets World Series victory on Oct. 16, 1969.

“As soon as that game was over, I ran from the press box down to the clubhouse,” Reilly said 39 years and one day later, as he traced the trajectory from the top of the stadium to the bottom with his finger. “There’s a picture of me in the 1970 yearbook, being doused with champagne by Jerry Grote. Those were my guys. They were the best.”

In addition to his daily responsibilities, first in ticket sales and later in the promotions department, Reilly also served as the V.I.P. handler for visiting celebrities and politicians, ran the Mets Speakers Bureau program and filled in as public address announcer at Shea for three weeks in 1966. He also wished four members of a British rock band good luck as they ran on to the field for an August 1965 concert.

“I said, ‘Break a leg, guys,’ and one of them said, ‘Thanks mate!’” Reilly remembered. “I don’t know which one it was because I didn’t know who The Beatles were back then.”

But Reilly’s fondest memories began on May 31, 1964, when he donned the papier-mâché, baseball-shaped head of the first mascot in Major League Baseball history. The Mets lost both sides of a doubleheader that day to the Giants, whose defection to California with the Brooklyn Dodgers after the 1957 season inspired attorney Bill Shea’s successful crusade to bring National League baseball back to New York. But, between games of that doubleheader, a star was born.

“The stadium was packed and I was nervous,” Reilly said with a laugh. “They had told me to play it straight, just walk out there and wave, but the kids started swarming down to meet me in the stands. I shook hands, posed for pictures, signed autographs. After that, I got cocky and started dancing. It was an instant hit. Back then, the fans might not have recognized the players, but they always recognized Mr. Met.”

As Reilly remembered the glories of four decades past, he struck up a conversation with a current Mets fan, 48-year-old software engineer Mark Szemberski, who was snapping photos of the now-shuttered stadium.

“Of all people to meet, the last time I’m at Shea — Mr. Met!” Szemberski exclaimed, as he posed for a picture with the unlikely celebrity. “You made my day. I hope they invite you back when they open the new stadium.”

Reilly handed Szemberski his business card, which features a photo of his younger self in a regulation Mets uniform, holding the outsized head that made him famous. The original Mr. Met is smiling broadly, as always.

“Baseball is tradition,” Reilly said, as he bid final farewell to Shea from a departing 7 train. “Mr. Met touched people then, and he still does. I think it’s important to remember how we used to do it, what Shea used to be like. If we do, there will always be a Shea Stadium.”

“The Original Mr. Met Remembers: When the Miracle Began” (138 pages) is available at iUniverse.com.