By Elizabeth O’Brien

The South Street Seaport used to be one of those attractions that New Yorkers would recommend to their out-of-town guests even though they rarely visited themselves, noted Peter Neill, president of the South Street Seaport Museum.

But that might be changing. With the near-completion of a $22 million gallery complex inside the early 19th-century buildings of Schermerhorn Row, the South Street Seaport Museum has sailed into greater prominence than ever before. The galleries lie on the top three floors of the Federal-style brick buildings on Fulton St. between Front and South Sts.

Flanked on Fulton St. by a Metropolitan Museum of Art gift store on the right and a United Colors of Benetton clothing store on the left, the new Seaport Museum complex occupies a central position that was part of the museum’s founding vision 36 years ago.

“Now, you can’t avoid us,” Neill said last Thursday.

Ten of the 24 galleries nestled above the retail stores will open to the press on Oct. 14 and to the general public sometime in early to mid-November. The first ten galleries were scheduled to open to the public on Oct. 14 as well, but the general opening was delayed to accommodate late additions to the exhibit, a museum spokesperson said. The remaining 14 galleries, which are to house the museum’s permanent collection, are scheduled to open next fall.

Visitors will be able to enter the new complex through Fulton St. or John St. From the admissions desk, they will travel up a narrow escalator into a courtyard, now glassed-in, that once linked the backs of the buildings. Riveted iron security doors on a brick facade are among the many original details that have been preserved throughout the galleries.

The 30,000-square-foot complex offers a vivid look at the city’s maritime history — in the very buildings in which it was lived. In the early 1800s, the seaport served as the World Trade Center of its time. Traders worked on Schermerhorn Row in the early 19th century, just as they work on Wall St. now, Neill noted.

“Let me tell you something, history is not boring,” Neill said.

As part of their lively walk through the past, visitors to the Seaport Museum will navigate the sloping wood floors of the galleries, and tall guests will have to guard their heads against the wooden beams of the original low ceiling. Exhibition space had to be fashioned from the irregular rooms on the top three floors of the Schermerhorn Row buildings, since the bottom two floors must remain retail space under the agreement that created the South Street Seaport mall in the 1980s.

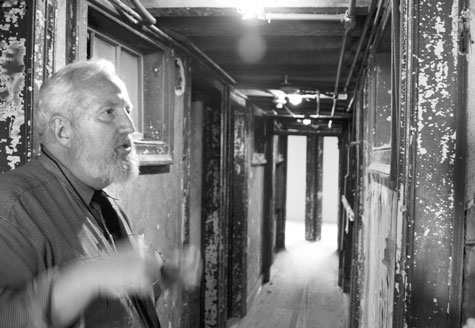

Adding to the museum’s authenticity are some spaces that the museum “restored as a ruin,” or stabilized but maintained in a state of disrepair, Neill said. These include a corridor of the old Fulton Ferry Hotel—immortalized in Joseph Mitchell’s story “Up in the Old Hotel,” first written for The New Yorker. Faded, peeling wallpaper from the late 19th century lines the walls. Small, windowless guest rooms lie off the corridor, and a faint black sign points the way down a staircase.

The museum’s permanent exhibit, “World Port New York,” will tell the stories of some 160 people who worked in the Seaport’s hotels, counting houses, trading companies, and warehouses. One is a young Irish woman who worked in the laundry room of the hotel.

“What you have here are whispered evocations of ghosts,” Neill said.

In some parts of the museum, the messages from the past are shouted. Original graffiti is preserved on a several walls, some dating as far back as Sept. 16, 1847. While those markings are not easily interpreted, other walls reveal ornately written names and a caricature brandishing a knife and saying “Stand Back.”

The museum’s first rotating exhibit in November will explore the legacy of slavery. “Portrait of America: Africans in the New World—from Captive Passage to Cultural Transcendence” will examine the forced migration of Africans, their enslavement in the Americas, and their subsequent cultural contributions.

The galleries that tell the story of the Seaport’s past had languished unused from the 1920s until the museum began construction, Neill said. New York City owns the land in the Seaport area, and the city contributed $5 million towards the restoration project. The Port Authority also contributed $5 million, with the remaining amount raised from private donors.

“All this value accrues to the city in the end,” Neill said.

Admissions to the museum will cost $8 for adults, $6 for seniors and students with a valid ID, $4 for children ages five through 12, and museum members at no charge. The price covers admission to all open galleries in the new space, the three older galleries on Walter and Fulton Sts., and tours of the permanently docked ships, including the Peking and the Wavertree. The Seaport is looking to sell the Peking for $12.5 million in order to help maintain the other ships, but Neill said there are no active bids.

Neill sees the museum as playing a significant role in the revitalization of Lower Manhattan. There’s much talk of creating a cultural center on the World Trade Center site, and of the 92nd St. Y possibly opening a Downtown branch, but the city should not forget the culture that is already in the neighborhood, he added.

For the museum, appreciating the Seaport’s history meant listening to the stories that the old buildings tell.

“The building speaks for itself,” Neill said. “Our job is to let it do that.”

Elizabeth@DowntownExpress.com