By Albert Amateau

“If I have another lifetime, I’ll do another book like this, maybe a biography of Mayor Robert Wagner, Jr.,” said Luther S. Harris. That would be a fittingly ambitious project, given the weight of Harris’ latest work. A Village resident for nearly 30 years, Harris is author of the recently published “Around Washington Square,” a history of the square and the Village, which he considers the beating heart of New York City.

Harris, who lives with his wife in the venerable 1927 apartment tower, now a co-op, at 1 Fifth Ave., has been delving into the history of the square and the Village for 30 years and spent the last 10 years writing and putting the book together.

In a recent conversation in the 1 Fifth Ave. co-op boardroom — which was the 1 Fifth Avenue Hotel office in the Roaring ’20s — Harris waxed eloquent about his love for New York City in general and for the Village in particular.

“Around Washington Square,” 323 pages of text, studded with drawings, photos and maps, with another 30 pages of indispensable notes and index, published by Johns Hopkins University Press, is a testament to that love.

“In the ’70s I got interested in books about the city but I never got the feeling from them about why and how the Arch was built, why Fifth Ave. developed the way it did and how the people with social clout were able to stop the Village and Fifth Ave. from becoming completely commercial,” he said. “Of course, the fact that this was where the new grid system and the old streets met was a bar to the kind of development that you see in Midtown,” he added.

“I lived in the city archives [in the Hall of Records on Chambers St.] And at the New-York Historical Society,” said Harris, recalling the hours he spent in research. “They have bound volumes of city proceedings going back to the 1700s. In the tax maps you can see every lot in Manhattan and its building history,” he added.

“I took a year off to look at early newspapers to get a feeling of the times,” he said.

Harris is enthusiastic about the help he has received over the years, from various friends and colleagues — Madelyn Rogers of the Seaport Museum and his late friend Sam Wagstaff, among others. Wagstaff was a collector of photographs who, Harris said, “put me onto stereograph cards with illustrations and photos from the 1850s. They were the popular entertainment of the day.”

Harris’ book follows the lives and works of the “people with social clout,” like Philip Hone — mayor of New York from 1826-1827, developer, philanthropist and “The Father of Washington Square” — a special hero of Luther Harris.

A contemporary Villager, former Mayor Ed Koch — shown in a photo in the book strumming a guitar — also plays a large part in the history. So does Raffaele La Guardia, better known as Fiorello (the Little Flower) — three-term Mayor of New York — born on Sullivan St. and raised until the age of 15 in South Dakota where his father was bandmaster in the Eleventh Infantry Regiment.

Garibaldi is here too, in the form of the nine-foot bronze statue, the first to be erected in Washington Sq. Park; the statue’s dedication was celebrated by Mayor Abraham Hewitt in 1888 with 30 bands playing, the Garibaldi Guard and three French military groups on parade. Also here is Robert Moses, whose plans for the Village failed, to the delight of Washington Sq. partisans who fought him for 30 years.

More recently, the Kimmel Center and the New York University School of Law buildings and their controversial stories are also discussed in the book.

The Village as a center of the arts is a major theme of “Around Washington Square” — Walt Whitman holds forth at Pfaff’s in the Coleman Hotel on Broadway near Bleecker St. in the 1850s. Alan Ginsberg joins Gregory Corso and Jack Kerouac in the San Remo on MacDougal and Bleecker Sts. in the 1950s. The poets Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch and James Schuyler drop in at the Cedar Tavern on University Pl. to hang out with New York School Abstract Expressionist painters Jackson Pollack and Willem de Kooning.

Readers can open the book at almost any point and read on without having to go back to pick up a first reference to a character or an intellectual or artistic movement. But every page has a surprising gem or an issue that makes you think about what goes on today.

Harris believes that New York City, despite common wisdom to the contrary — is a humane city. “I was appalled at Ric Burns saying [in his 1999 documentary film, “New York”] that greed created New York. Look at City College, established as a Harvard for the poor. The public hospitals, the settlement houses,” he exclaimed.

Harris also explodes popular myths. The famed hanging elm at the northwest corner of the park was never used for hanging, he insists. “By law, gallows were erected for each execution,” he explained. But he agrees the tree may be more than 300 years old. It likely grew on adjacent farm property, which was incorporated when the potter’s field was transformed into Washington Sq.

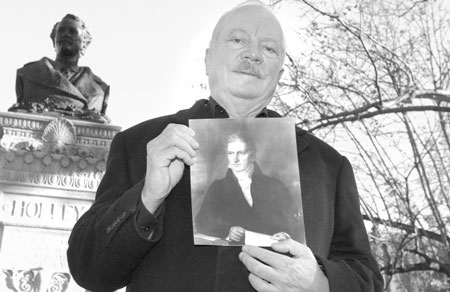

Harris wants to convince the city to erect a statue to Philip Hone, whose efforts turned the common burial ground into Washington Sq. “Hone was admired by everyone until his death in 1851 and now he’s almost forgotten; there is no public monument to him anywhere,” Harris complained. He recently convinced the New-York Historical Society to allow him to make a plaster copy of a life-mask bust of Hone.

Harris wants a monument to Hone, comparable to the heroic Garibaldi statue, to be erected on the west side of the park where the bust of Alexander Holley is now. Holley was a chemist who brought the Bessemer steel process to the U.S., which helped make the fortunes of Mayor Hewitt and his son-in-law Edward Cooper, a former mayor.

“Hewitt and Cooper were the most prominent residents of the square at the time and that’s surely why Holley’s bust is where it is,” said Harris, who wants Holley moved to make way for Hone.

A heroic monument with a head modeled on the Hone life-mask is what Harris has in mind. “The trouble is, the Parks Department doesn’t want any more statues of 19th century men. But Hone was unique,” Harris said.