New York City condo owners and co-op managers may soon learn that there are other major costs to climate change beyond hotter summers, stronger storms, flash floods and apocalyptic smoke.

Time is running out for the owners of large residential buildings throughout the Big Apple to get in compliance with a 2019 climate bill that kicks in January 2024 that aims to curb their building emissions.

Many co-op and condo owners across the city, however, are worried that the implementation of the legislation, known as Local Law 97, will bring stiff penalties for building owners that fail to reduce their emissions standards below a set amount.

Some owners are concerned that the penalties will lead to a spike in their assessments and monthly maintenance, since the cost to retrofit old co-op buildings will cost millions. Those costs will ultimately be passed on to every resident in one way or another — through higher common/maintenance charges and/or rents.

Now they’re faced with a real quandary: Undertake costly technical upgrades that could break their bank accounts, or accept expensive penalties as the cost of not only doing business, but also keeping roofs over their heads.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a multi-part series on Local Law 97: Part 2 will run on Sunday, July 30.

What does Local Law 97 require?

Under the rules, buildings 25,000 square feet or more must meet new energy efficiency standards and comply with greenhouse gas emission limits by 2024, with stricter requirements going into effect in 2030 and getting progressively tougher through 2050.

The purpose of the new rules is to reduce building emissions by 40% by 2030 — compared to 2005 levels — and 80% by 2050. Nearly 70% of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions come from buildings and regulators want to reduce them.

While most modern buildings will meet the 2024 requirements, many older condo and co-op buildings will not—and are therefore likely to face fines. The fines will also rise in 2030 and beyond as the emission standards get stricter.

Most residential buildings are already in compliance with 2024 targets, with 21% not meeting standards, according to PlaNYC, the city’s strategic climate plan that was released in April. However, that number will jump to 85% by 2030 as the stricter standards kick in.

The legislation as written has broad political support; the City Council overwhelmingly passed the legislation 45-2 in 2019. However, as 2024 approaches many middle-income co-op owners are voicing their opposition to a central component of the law: the penalties for non-compliance.

‘Money we don’t have for work we don’t need’

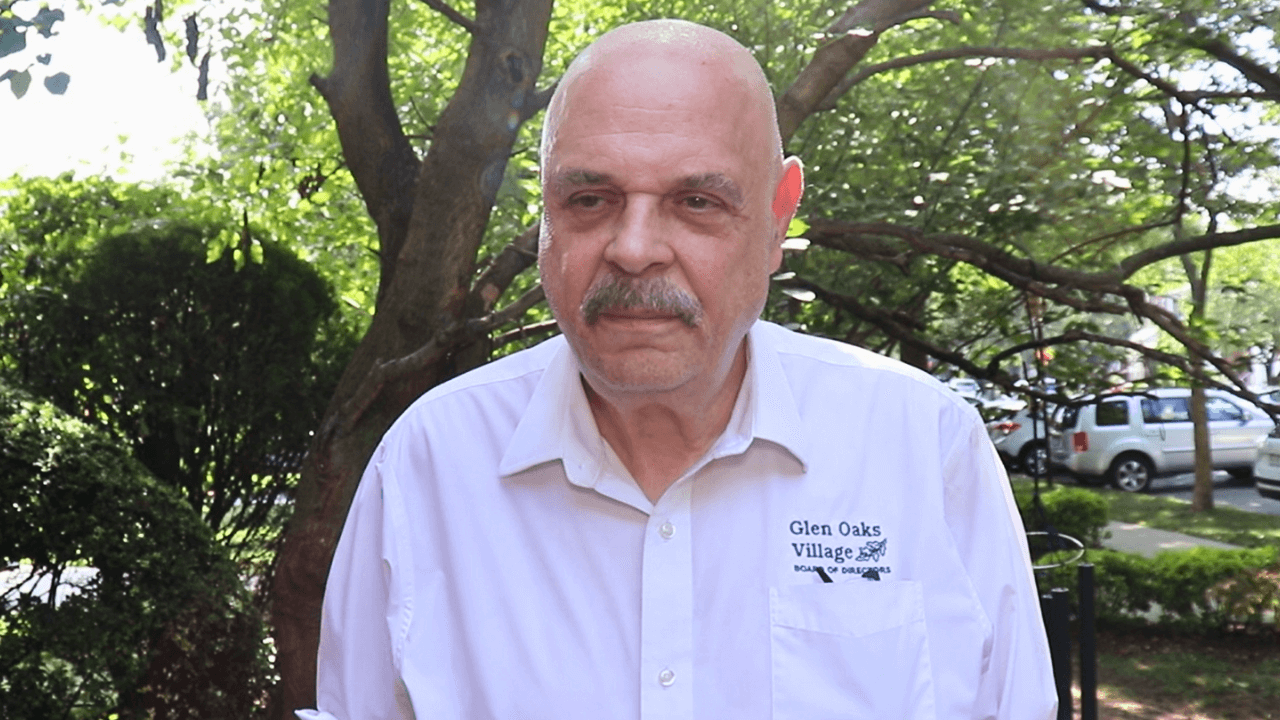

Bob Friedrich, board president at Glen Oaks Village in eastern Queens, argues that the legislation hurts the middle class. He said that the co-op owners in his 2,904-unit development are likely to be hit with large assessments since it will cost millions to retrofit the property to comply.

He said that the cost to bring the development in full compliance with Local Law 97 would approach $50 million. He said the entire development — built shortly after World War II — would have to be rewired, with electric heaters installed in all units. He said it would cost about $20,000 per unit.

“This is money that we don’t have and for work we don’t need,” Friedrich said.

Friedrich, who has been working with an energy consulting company, said that the Glen Oaks development would be fined $394,000 each year starting in 2024 if no work is done, which would jump to $1.5 million per year in 2030 and continue to climb. He estimates the penalties would total about $38 million by 2050.

The development, he said, currently has 96 boilers that run on oil and gas that are all in working order. He said if the board were to upgrade the boilers to be the most energy efficient available it would cost $24.5 million — or about $9,300 per unit — and they would still not be in full compliance with Local Law 97.

The $1.5 million penalty in 2030 would be reduced to $880,000. He said the board prefers boilers, saying that heat pumps for electrical systems do not generate enough heat when the temperature falls below 30 degrees.

Friedrich said that many of the residents will struggle to pay higher assessments, noting that the 80-year-old coop development is occupied by teachers, nurses, civil servants and senior citizens—and is the essence of affordable housing.

“This is the last bastion of affordable housing where you can buy an apartment for $250,000 to $300,000,” Friedrich said.

Long-time Glen Oaks co-op owner Arlene Bett, 60, said that the cost of the impending penalties and the required upgrades are troubling.

“I’m terrified,” Bett said, whose current maintenance is about $600 per month. “The thought of it just gives me anxiety.”

“If Local Law 97 goes into effect with the penalties and everything that they’re asking us, I’m going to have to give up certain things in my life,” Bett claimed.

Complying with the law is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Each building has its own specific carbon footprint, given its age, its maintenance, its usage, and the heating and cooling systems it employs.

The city tabulates emissions based on the sources of energy a building uses—such as oil, gas and electricity—as well as its consumption, in relation to the square footage of the building. Owners have to report their 2024 greenhouse gas emissions by May 1, 2025.

However, rent-regulated buildings and owners of affordable housing complexes are not subject to the same emission requirements per Local Law 97. These owners are able to comply via a “prescriptive pathway,” which involves conservation measures including upgrading lighting, weatherization, and air sealing.

Homeowners are not subject to the law.

Costly conversion to electricity

Residents living in the Queens View co-op in Astoria — a 726-unit complex constructed in 1950 — are likely to face fines much like the co-op owners at Glen Oaks in order to meet the requirements.

Alicia Fernandez, treasurer of Queens View board, said that the annual penalty for the entire co-op starting next year will be $49,554, with the fines jumping to $496,000 per year from 2030 and then getting successively higher.

Fernandez said the co-op will have to switch all of its gas boilers to electric heaters in order to comply with LL97. She said the EN Power Group, an engineering firm, is currently conducting a feasibility study to determine the overall costs of the potential upgrades but a preliminary estimate puts the figure at $20 million.

That price tag would likely balloon to $40 million after additional costs such as removing lead and asbestos during installation are factored in, she said.

“There’s always going to be conditions you encounter that put costs beyond the original price of the project,” Fernandez said.

“The fines and the timeline are just unrealistic,” she added.

Fernandez said the c0-op faces issues. It will not be able to take out a loan to pay for a potential switch to go full electric until at least 2030 – since they already have a loan to cover other efficiency upgrades that come short of 2024 standards.

Meanwhile, Warren Schreiber, board president of the 200-unit Bay Terrace co-op in Queens, said that it would cost approximately $4 million to convert to electricity and be in full compliance to avoid penalties.

“We have 16 buildings, and within those buildings, we have 16 boilers,” he said. “In order to meet the requirements without paying a penalty, we would have to replace our boiler systems.”

The cost falls on the coop unit holders. “You’re talking anywhere from $20,000 to $25,000 per family. That’s a lot of money.”

To cover the cost, Schreiber estimates that shareholders would see a 30% maintenance increase: “In the case of my property [unit], our maintenance is fairly low, but that would equal about $200 a month.”

Schreiber, however, said that the city is right to target emissions.

“I’m not a climate denier. I’m absolutely not. I believe that it is an existential threat to the world,” he said. “I have a granddaughter, 15-years old. I want to leave her something — a world that she can enjoy — but she’s also going to need affordable housing.”

Programs to help cover costs

But advocates for the legislation argue that there are programs to help co-op boards get in compliance — including loans and grants — and that the number of owners that don’t meet 2024 standards is small.

Furthermore, the legislation includes a provision that waves or reduces penalties for building owners that make “a good faith effort” to comply.

Many owners are eager to find out what that means and whether they can get out of the penalties if they are unable to meet standards.

The DOB, which is in charge of overseeing Local Law 97, released rules late last year that detailed the emission limits for different building types. This summer the DOB will be defining what a good faith effort is.

Geoffrey Mazel, a partner at the law firm Hankin & Mazel and counsel for the Presidents Co-op and Condo Council, said the “good faith effort” needs to be spelled out clearly.

“It has to be clear and discernible,” Mazel said. Otherwise, he added, it will be at the whim of the DOB and “I don’t have much faith when the DOB is being the judge and jury on a case-by-case basis.”

The law also will reduce penalties for other mitigating factors, such as financial hardship or an unforeseen event.

The city, however, is not looking to take a draconian approach, officials say.

“The general principle we are going to take is that we are not looking to impose penalties, but we need building owners to do the work,” said Rohit Aggarwala, who is NYC’s Chief Climate Officer and the Commissioner of the Dept. of Environmental Protection. “If you’re sticking your head in the sand, you shouldn’t expect forgiveness. But if you are genuinely getting started and you’re just a little late, then chances are we will do everything we can to be helpful to you.”

Costa Constantinides, the former Queens City Council member who sponsored the 2019 law, said the legislation was drafted to give building owners decades to address their carbon emissions. He said building owners typically make infrastructure changes every 10-15 years in order to keep them in good order.

Laura Popa, the NYC Deputy Commissioner for Sustainability, agreed.

“The law was drafted to support a transition over a long period of time,” Popa said. “The ultimate end date of the law, where the goal is to achieve zero emissions, is 2050. That is a 30-year transition period.”

“The idea is to get some low hanging fruit that needs to be done in the beginning. And then as time goes on, the emissions limits get more stringent.”

The city has put programs in place to help building owners meet the standards.

The main program is what is called the New York City Accelerator, which is like a help desk for owners, providing resources, training, and one-on-one expert guidance.

Building owners can fill out a form, or call and find out a rough estimate of what they need to do to comply based on data the city has gathered from the Dept. of Finance and Dept. of Buildings.

“The Accelerator can be like a coach or a helping hand for the building owner,” Aggarwala said.

He said representatives with the program will advise owners to hire an engineer to come up with a compliance plan; provide details on grant programs; and discuss loan programs, if necessary.

Aggarwala said that there is a grant program to help building owners cover the cost of hiring an engineer to help them come up with a plan.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, a public benefit corporation that aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, offers grants via its “FlexTech program” where as much as 90% of the cost of hiring an expert is covered.

The city is also offering a loan program, known as NYC PACE, that will provide the capital building owners need to retrofit their buildings, allowing payments to be spread over as long as 30 years, Aggarwala said.

The NYC PACE program, however, is not well suited for co-ops and condos since existing mortgage holders typically have to sign off on such loans. Most buildings — as well as unit holders — have loans, and mortgage holders are reluctant to sign off since the NYC PACE is a superior form of debt.

Aggarwala said that building owners can find loans elsewhere. He said that the New York State Green Bank offers low-cost loans that are readily available.

“A co-op or a condo that has its books in order and has reasonable reserves and a good history should have no trouble,” Aggarwala said.

Aggarwala also said that there are also grants available — particularly in low-income neighborhoods — from NYSERDA or Con Ed. He said that they are also waiting to see what comes of the Inflation Reduction Act that the Biden administration passed last year that is expected to provide funds for building owners going green.

The second part of this series, which runs on Sunday morning, will focus on the race to meet the guidelines in Local Law 97, plus the push by some City Council members to change the law before it’s too late.