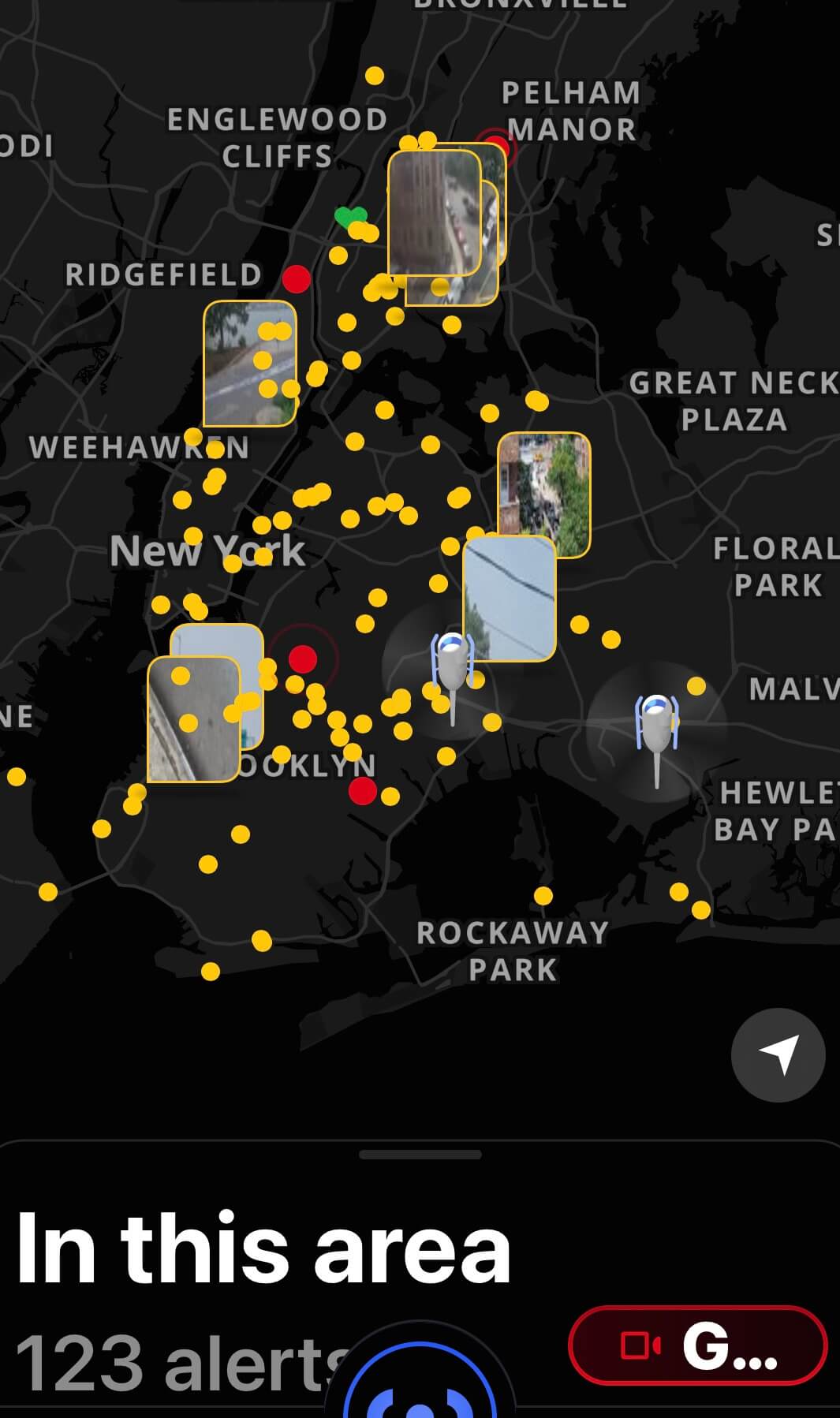

The Citizen app, fed in part through information obtained via NYPD radios, connects more than two million New Yorkers, allowing them to monitor incidents citywide in real-time.

Among those who rely upon police information fed through the Citizen app are volunteer violence interrupters. They learn where crime occurs, then head to the scene so they can help comfort those affected and quell any further acts of aggression in the community.

Then there’s the army of reporters, photographers and videographers in the city’s press corps who rely upon the Citizen app, police scanners and broadcasting services to chase and break news as it happens, to provide independent accounts of incidents that all readers and viewers can trust.

Yet all of them would be shut out of the NYPD information pipeline should the department fully encrypt all of its radio communications citywide, just as it has done this month in six Brooklyn police precincts.

Because of this change — something which appears to be part of a testing plan, according to Police Commissioner Edward Caban — the public is now left in the dark regarding breaking news in much of Brooklyn North, other than what is broadcast over a citywide channel.

And, insiders say, that too may soon come to an end — as the NYPD has its sights set on encrypting all of its communications by the fall of 2024. Though the NYPD maintains this effort is being done for public safety purposes, others charge it is their way of controlling the narrative and infringing upon the public’s right to know and report.

‘Nobody is going to have any idea of what’s going on’

Citizen has been operating on a quarter of New Yorkers’ phones since 2016, breaking news 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The app allows residents to know what is going on in their communities and is relied on by some community groups to get information about breaking news.

The app relies on residents reporting incidents through the app, but also, scanner radios that are monitored by Citizen staff.

Representatives of Citizen have expressed concern about the potential loss of NYPD radios, but they say they are hopeful a solution is found to keep the public informed.

Numerous community groups use the Citizen app to know what is happening in the community and to also contribute information to the public.

Pastor Gil Munroe of the God Squad, an amalgamation of more than 100 clergy, work on the streets to quell and to mediate squabbles that turn violent. Sometimes they respond to incidents, including shootings, where they talk to the community and try to remove the urge to take revenge – a common issue when gang violence flares.

“We use it for informational purposes, so when we see it on Citizen, we try to confirm it with the police and people who live there or a church close and ask them to step outside and see what is happening,” he said. “It’s just one of our tools that we use.”

Many news organizations and professional groups use the Breaking News Network (BNN) paging app to receive notifications of emergencies throughout the tri state area. A full encryption of the NYPD would be a severe loss to the city, officials say.

“Not just the news media relies on us, but public safety uses us because they can’t monitor it themselves,” said Steve Gessnann, vice president of BNN, the service that uses scanners to put out notifications. “We have hospital corporations, outside police agencies who rely on us and don’t have dedicated people to know what is going on. If we didn’t have access to NYPD we would have to wait for the press office to send notification that something happened – nobody is going to have any idea of what is going on.”

‘You won’t get anything’

Oliya Scootercaster, owner of Freedom News TV that provides video to nearly every television news station in the tri state area, said a full encryption would be disastrous.

“We can do our job now, but if encrypted radios come, we can only do our job when police notify us, then it is police controlling the press,” Scootercaster said. “This should never be the case. If we can’t know what is happening, we then find out way later. It’s not that the police are doing something wrong – it’s just our job to see what’s going on, to document and if we are not there can’t present it, the scene could be cleaned up.”

She said parts of New Jersey are encrypted, and as a result, few people know what the police do there.

“There may not be a scene any more when we are notified and so our response would be delayed if we wait for the police to tell us and then there is no video, nothing,” Scootercaster lamented. “Special Operations frequency is the important stuff – I don’t understand how the press will operate so it’s strange that we are being blocked, especially in New York City.”

Adam West Balhetchet, a news chaser with LoudLab News NYC that also supplies video to television news, said his business model of supplying television with overnight crime footage would be severely damaged should all radio frequencies be encrypted.

“Our priorities are the homicides, mobilizations, collisions so we need to know sooner than later,” said Balhetcht. “I don’t want to show up after the tape is down. You call public information and they don’t have much info. … If we can’t get a visual on a crime scene, there’s no sale for other stringers, news photographers who are expected to get photos of crime scenes and for TV stations. What will everyone be doing?”

Joe DeMaria, a veteran news photographer working since 1958 and still working part time for the New York Post, has been listening to radios his whole career.

“We might just have to rely on tips, how else will we cover things?” he said. “How the hell will you know? Will people be chasing ambulances? I don’t understand why they are doing that. Not like it used to be. We used to be friends, now we are the enemy.”

Jerry Engel, a former New York Post photo editor and news chaser since the 1950s, said he believes the police are cutting off the radios because they see the press not caring. However, he believes the encryption system won’t work properly because of the size of the department.

“I don’t think newspapers give a s–t, and TV is cutting staff reporters and the new people don’t even know what day of the week it is,” Engel said. “I think the business is on the ropes, If encryption ever happens it will be the end you won’t get anything.”