For the first time in 342 years, a New York court ruled that a criminal defendant can be convicted by a jury of 11 after the defendant tried to tamper with the jury. The hallowed 12-person jury, which originated in medieval England and may have links to Jesus Christ and his Twelve Apostles, has become one of the most embedded features in American jurisprudence.

In its ruling last month, the New York Court of Appeals found that a defendant’s “egregious conduct” in confronting the foreperson of the jury at his home and instilling a fear of harm to the juror and his family amounted to a forfeiture of the defendant’s right to a 12-person jury.

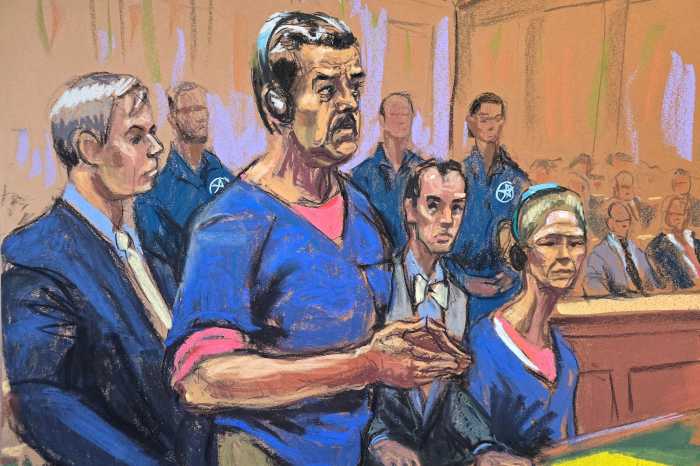

The facts are not really disputed. The defendant, Derek Sargeant, after a violent encounter with a 20-year-old woman in the basement of his Queens home, was charged with possession of two revolvers, 81 rounds of ammunition, two machetes, and 2,513 blank credit cards and retransfer ribbons used to forge plastic cards. After the presentation of evidence and the parties’ summations, the jury commenced its deliberations. As is customary when deliberations begin, alternate jurors were excused.

On the morning of the second day of deliberations, the defendant’s lawyer advised the trial judge that his client had a serious migraine and asked the judge to suspend deliberations for the day. The judge agreed and adjourned the proceedings.

But that afternoon, the judge received a panicked call from the foreperson of the jury. The foreman told the judge that “something happened” and that he could no longer be a juror. The judge reconvened briefly that afternoon, advised the prosecutor and defense attorney about the foeman’s call, issued a warrant for the defendant’s arrest, and scheduled a hearing for the following morning.

At the hearing the next morning, the foreperson told the judge that as he was returning home the previous afternoon, a man approached him “on behalf of” the defendant. He told the foreperson that the defendant was innocent and was “being extorted.” He gave the foreperson several documents from the case. The encounter lasted less than a minute. The foreman, “in a bit of a panic” and concerned for his family’s safety, called a friend, told him that the man who accosted him was the defendant disguised with sunglasses and a jacket with a high collar.

The trial judge excused the juror. He found that there was “no doubt” that the defendant had personally tried to orchestrate a plan to tamper with the jury by feigning illness in order to leave the court early in the day, confront the juror, and cause the juror to upset the deliberations based on the juror’s “overwhelming fear” for his family’s safety.

So, without any alternates to replace the juror, the judge had the choice to declare a mistrial or continue the trial with 11 jurors. For the first time in New York’s history, the judge chose the latter.

And it was the correct choice. The defendant’s conduct was so flagrant, and so offensive, that it justified the judge’s decision that the defendant forfeited his constitutional right to a 12-person jury. The principle is clear: a defendant enjoys numerous constitutional rights, but by engaging in flagrant misconduct, he can forfeit those rights. Thus, courts have found that a defendant can forfeit the right to an attorney, to confront witnesses, to be present at the trial, and to represent himself.

In sum, as the New York court concluded, jurors are ordinary citizens who are enlisted into a process critical to democracy. Their lives are disrupted for a time, for which they receive a modest stipend. They are not simply interchangeable parts that can be substituted at will in order to protect a defendant’s constitutional right to a 12-person jury. When a defendant exhibits such blatant disrespect for the sacrifices jurors make to the American justice system, the defendant relinquishes his right.

This is a very narrow decision based on a unique set of facts. It will be a rare trial in which a defendant will be found to have forfeited his right to a 12-person jury. But just as a defendant’s rights are protected from governmental abuse, so may a defendant’s abuse of those rights make him pay a price.

The origin of the 12-person jury isn’t definitively pinpointed but may stem from ancient Germanic customs and solidified in 12th-century England under King Henry II, evolving from local groups of “swearers” or “presenters” who vouched for facts, eventually becoming the decision-makers, with the number 12 potentially linked to religious (Apostles) or administrative (Frankish inquests, Danish ‘wager of law’) traditions, becoming standard practice enshrined by the Magna Carta and carried to America as a key right against oppression.

In early Britain, the Saxons also used something similar to a Grand Jury System. During the years 978 to 1016, one of the Dooms (laws) stated that for each 100 men, 12 were to be named to act as an accusing body. They were cautioned “not to accuse an innocent man or spare a guilty one.”

Bennett L. Gershman is a distinguished professor at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University