By Lincoln Anderson

I’d been down at 1 Police Plaza late one night, looking at the action sheets for the Downtown precincts, and one in particular caught my eye.

Michael Roth, M/W/32 (police report lingo for “male, white, age 32”), had been arrested in the strangling of a 21-year-old woman in the hallway of a building on E. Ninth St. Roth and the woman had been sleeping on different landings, and in the morning she was found dead.

I called John Penley about it. He said Roth was known as “Sloth,” and that there was a guy I should talk to who would know all about it: Bob Arihood.

Bob came over to our office. He was a big, burly guy in a black T-shirt and blue jeans. And he brought along a big photo — a black-and-white print — of Sloth in a wheelchair with a cast on his leg; next to him in the photo was a white-haired guy holding some sort of funky video camera, who Arihood explained, was “Mosaic Man.”

“Sloth is one of the major characters,” Bob said. “He went into a pizzeria down here on Avenue A and threatened them and they broke his leg and put him into a garbage can.”

That’s how I first met Bob, and it was a typically gritty Bob story. (Sloth eventually beat the rap.)

Bob was a documentarian of the street life of Avenue A — not just as a photographer, but also as an oral historian, because he knew everyone’s story — and could recount those stories so well.

Sometime later, Bob invited me over to his place to check out his photographs. On his back wall he’d set up a sort of rotating gallery of black-and-white prints of Avenue A figures. I asked him about each one and, in turn, he’d relate the story of each subject, in a wistful, almost world-weary voice.

Each print was beautiful in its own way. There was “Hot Dog,” “Loan Shark Bob,” Lawrence, “John the Communist.”

“Ah, yes…Lawrence…,” he’d begin, or “Ah, yes…Hot Dog… .”

There was a photo of a man with a cast on each arm — Bob said he didn’t know how he got that way — and assorted guys with kooky hats.

Some of these folks were still around, some were dead, some had just vanished to who knows where.

One image showed what looked like a black garbage bag on the ground jammed up against the wall of the old Leshko’s restaurant, at Seventh St. and Avenue A. It wasn’t a bag, Bob explained, but a person so severely wounded and withdrawn that he had curled up into virtual nothingness.

In May 2000, Arihood raised the alarm about the plight of Ray’s Candy Store on Avenue A. After years of satisfying the neighborhood’s craving for hot dogs, egg creams and ice cream, Ray feared his lease might not be renewed.

Ray’s was “like an agora,” Bob told me then.

“This is the end of the neighborhood,” he said. “He’s the last place to hang out and talk. … It’s a public forum — I talk to doctors, lawyers out there. It’s a meeting place.

“Most of what I photograph is right there in front of Ray’s,” he said. “I’ve got five years of it on film, from murders to live sex on stage. I was watching the change [gentrification]. It’s all kinds of people, not just the bums. It’s a cross-section that corner, from the bottom to the top.”

He’d been hanging out at this “crossroads of the East Village” since 1984, back when he used to drink beer and smoke cigarettes there. He’d seen it all, from when the neighborhood was more dangerous, which he felt had made it more vibrant and exciting.

Drawn by his photos and his stories, I wanted to do a profile of him. Penley, an East Village activist who used to shoot for The Villager, told me that Bob was very private and had even refused the Times’s request to do an article on him. Good luck, he said. Eventually, though, Bob agreed to do an interview with The Villager.

From then on, he started contributing his photos — and just as important, his story tips — more and more.

At one point, he got a police scanner and started monitoring it for local shootings and other mayhem — much of which he said the police never reported.

It was always fun to go over and shoot the breeze with Bob and his clique of buddies standing out in front of Ray’s on a Friday or Saturday evening — and, again, just as important for me, to get story tips and ideas.

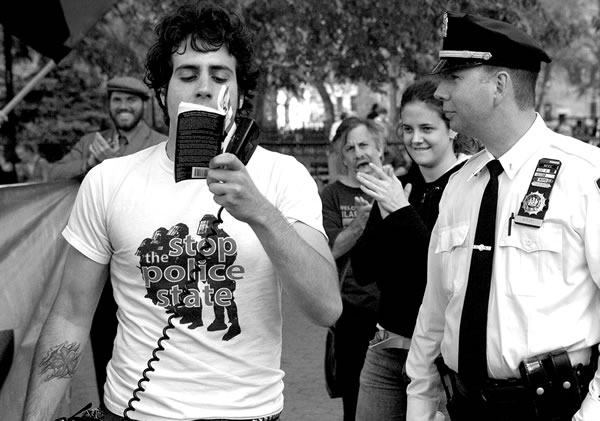

We worked on stories together — like during the Republican National Convention in 2004. He put me in touch with two teenage girls who had been held on Pier 57 for 50 hours — far in excess of the regulation 24-hour time in which arrestees are supposed to be arraigned. That was the N.Y.P.D.’s pre-emptive strategy during the R.N.C., to hold the protesters so they couldn’t go back on the streets.

He’d steer me toward interesting people to write about. One was Jim Flynn, a young Studs Terkel who had compiled his extensive interviews of the Tompkins Square Park homeless into a self-published book, “Stranger to the System.” Leroy Lessane was another, a homeless former actor who would collect so much stuff that the authorities would eventually cart it all off in a garbage truck. Bob felt Leroy was being treated unfairly.

Bob always felt Jim Power, the “Mosaic Man,” was one of the most interesting characters to follow, and it was with a photo of Power that he started his blog, Neither More Nor Less, in 2006.

Another favorite was old-timer John Dikun, a former conductor on the Third Ave. El who’d been a regular at Vazacs bar for decades — but only twice a week, a strict schedule back from his days of driving the trains.

Bob was a character himself. For about 10 years, he had a female squirrel named Fred. She just appeared on his doorstep one day, came in and stayed. He became such a squirrel authority that an East Village vet referred “subway gunman” Bernie Goetz to him when he got a pet squirrel.

Above all, Bob was passionate about what he covered. For example, he felt it was essential that people see his photo of the inside of the slush-covered Con Edison junction box on E. 11th St. that electrocuted Jodie Lane when she walked her dogs over it in February 2004. Bob’s photo showed what a shoddy job the workers had done splicing together the wires — using cheap electrical tape — and that these poorly wrapped wires had been touching the box’s sides, causing the fatal voltage leak.

After Critical Mass was “hot” for about a year following the R.N.C, he covered the anarchic bike rides. But in his pithy, humorous way, he dismissed them as “temper tantrums on wheels” — though he was still dedicated to covering them.

As seriously as he took his craft, he also had fun with it. In February 2006, we ran a photo story of Bob’s about “Cowboy Stan” and the demise of his beloved pit bull Tarzan. Stan grabbed every copy of the paper he could find in the East Village and started selling autographed copies of them to people for $1. I was a bit concerned — but Bob found it hilarious.

At one point, though, we’d had a disagreement over a photo for Page 1, and he’d been unhappy with how some of his images had been cropped in the newspaper.

Ultimately, Bob wanted more control over his own photos and stories, and he wanted to start writing, too, and in his own unique voice — and that’s why he began blogging.

Penley assured me Bob would come back to the newspaper because he “lived for The Villager.” But the technology was there, media was changing — and blogging allowed him to go solo.

And he flourished. Not only did he cultivate a devoted readership, but I think the blog also gave him a whole new set of friends. This past summer, with a smile, he told me about how all the East Village’s bloggers had, for the first time, met face to face at a party at the home of a guy named the Chillmaster, and how he had enjoyed dancing there.

He was proud that his blog was required reading for an N.Y.U. journalism course. The Village Voice awarded him “Best Personal Blog” in 2009. I think he was really at a highpoint.

Yet, at the same time, two years ago, he told me it was getting harder to keep doing the blog. The pressure of finding new material was tough. Plus, the neighborhood had gotten so much tamer, in his view, it was hard to find news stories. When he had a big story, he’d get 20,000 hits and it was exciting. But when he didn’t have good stuff, the hits would drop down to 300 and it was disheartening. Blogging was for younger photographers, he said, at one point; plus, he felt he’d already covered everything that was out there.

But when the Department of Health was cracking down on Ray’s earlier this year, Bob was extremely concerned, and he covered it in his usual hyperlocal way — showing Ray wiping down countertops, scrubbing grilles.

I biked over one night to check out the story and Bob, outside the store as usual, called me over: “Lincoln! Lincoln!” Ray was really on the brink, he said, the situation had never been this perilous before. Meanwhile, Gothamist was linking to Bob’s posts and his hits were going through the roof.

As I biked off, Bob said, sort of almost scolding himself, “This is what I was trying to get away from.” But I just laughed inside, thinking to myself, “No, Bob — this is what you love!”

He’d told me he planned to stop the blog at the end of August, but he was still at it right up to the end.

He also said he already knew what image he was going to end the blog with. I guessed: Ray? Mosaic Man? L.E.S. Jewels? He just grinned wryly and wouldn’t say.

It was a Saturday night two weeks ago and I was going over to Avenue A to talk to Bob. I’d gone on vacation and wanted to tell him about it, and I was interested to get his take on Occupy Wall Street. I guessed he might be a little cynical about it — yet would love photographing it as a visual extravaganza.

I looked for him in his three usual spots: by the Tompkins Square entrance at Seventh St. and A; outside Ray’s; and, finally, inside Ray’s. Not there. Then I noticed the small sign and the burning candles on the sidewalk in front of Ray’s ice cream kiosk. Chris Flash and Amy Sanchez, who were inside Ray’s, told me, yes, it was for Bob. I couldn’t believe it. After my initial shock, there was a second where I just wanted to lash out in anger and punch something — like Ray’s kiosk. No! It couldn’t be!

I had been coming to talk to Bob, just like so many times before, but he was gone. I’d been away on vacation when he died. It just seemed crazy.

For all the time I’ve been at The Villager, he was a constant presence. We worked together, became friends, sort of drifted apart for a while, and then became friends again, which I was glad for. If anything in this world seemed permanent, it was big Bob standing there with his camera on Avenue A.

“When I heard about Bob, I stopped breathing. It was shock,” Ray told me that night. “Without saying a word, tears came down. He was my best friend.

“Whenever I need help, I would always go to him. He helped me with my Social Security. I was bankrupt — he made people aware I am suffering. To me, even though I am older than him, he was like my big brother.”

A young woman whose name I didn’t catch said she was new to the East Village and had met Bob just two months ago.

“I’ve read every single post he’s ever done,” she said. “I read all five years. Oh my God, it gave me everything about the neighborhood.”

Another woman who was Arihood’s neighbor for years, but said she doesn’t have a computer, also relied on him for local information.

Krissy Hursch was putting down flower petals and a message — with a pink lipstick kiss planted on it — at the growing memorial that Saturday night.

“I heard about the Bean going out of business — Starbucks squeezed them out,” she said. “You find out about something like that, and you call Bob and find out about it. I don’t have a computer; he always had his camera on and he’d show me stuff — like somebody got shot that didn’t make it into the papers. I always felt that Bob had my back in life.

“I liked him because he told it like it was.

“It’s not going to be the same walking by here,” she said. “Avenue A’s not going to be the same.”

I think, in writing this piece, that’s exactly what I was trying to say.