By John Doswell

On Sept. 29, 1947, Pier 57, a Grace Line Pier on the North River between 15th and 16th Sts., caught fire. The fire started underneath the pier in the creosote-soaked piles. It was suspected that a tugboat had discharged some hot coals just prior. The fire destroyed the $5 million dollar pier and was called the worst pier fire in the city’s history. Over 200 firefighters responded, along with several fireboats including the still-active Firefighter and the now retired but still functioning John J. Harvey. One hundred forty firefighters were injured, most due to smoke inhalation, since the fire burned for over two days, creating billowing clouds of black smoke that caused the West Side Highway and several other streets to be closed. For a period, the fire threatened a second Grace Line pier, Pier 58, directly north, as well as Pier 56 just south. However, both piers escaped damage. Two more engineers were injured when the headhouse portion of the pier collapsed without warning on Oct. 1.

Within months, planning for a replacement pier had begun, this time to be built with a much more fire-retardant type of construction. The concept called for a pier supported, not by wood piles, but by three giant concrete boxes. This was inspired by the successful use of floating concrete breakwaters for the invasion of Normandy during W.W. II. The idea was the brainchild of E.H. Praeger, former chief of the Navy Bureau of Design.

Two years later, the commissioner of the Department of Marine and Aviation, Edward F Cavanagh, Jr., announced the beginning of work on the new pier. The original estimate was $7,500,000, of which $4,500,000 was allocated for the substructure. The new design would allow passenger traffic to drive down into the basement alongside the bulkhead, unload and be taken by elevator to a grand waiting hall on the second level. Meanwhile, trucks with freight would travel by large ramps directly to the second level without encountering passengers. The other two basements were to be used for freight storage, to be accessed by giant elevators.

Work began on Aug. 30, 1950. After several speeches by city fathers at 11 a.m., dredges began to remove the remnants of piles leftover from the 1947 fire. However, a few minutes later, the noon whistle blew and work stopped for lunch. Ultimately, 2,300 old piles were cut at the mud line via a large underwater chainsaw. They were then covered with two feet of gravel, which was to be base for two of the three concrete boxes.

Meanwhile, a site was needed to build the boxes. Eventually a man-made lake next to the river near Haverstraw was selected as the construction site. It took 20 days to pump 210,000,000 gallons of water out of the lake, until a dry bed remained. A concrete work floor was then laid, and construction of the caissons began. The dimensions of these boxes was staggering. Box number 1, destined to become the base of the headhouse alongside the bulkhead, was 367 feet long by 87 feet wide. It was 28 feet tall and, when complete, would weigh 19,000 tons. If positioned vertically, this structure would be as tall as a 36-story building. Boxes 2 and 3 were identical, designed to support the finger portion of the pier. Each of these two boxes was 360 feet long by 82 feet wide and almost 33 feet tall. Each weighed 27,000 tons. Altogether, 34,000 cubic yards of concrete were used.

On July 29, 1952, the first box was floated down the river. Prior to that, the lake had been flooded by means of a 12-inch pipe that connected the lakebed to the nearby river. At the completion of flooding, the three boxes were now afloat, held in position with lines. A break in the dike between the lake and river was dug, and a channel dredged. Six Moran tugs moved in and took box number 1 under tow. It was expected that it would take almost two days to move this giant object from Haverstraw to its final location at the pier site. Instead, it took only 13 1/2 hours, disappointing photographers who had hoped for a daylight arrival the following day. Once in position alongside the bulkhead, box number 1 was filled with water and sunk.

About a month later, the larger units, 2 and 3, which floated about five feet deeper in the water, were floated down river in like manner. Box number 2 scraped the bottom at one point on its journey but box 3 made it all the way without grounding. By Sept. 18, 1952, all three sections were in place. Boxes 2 and 3 rested on the gravel beds that had been prepared almost two years earlier. As these caissons were sunk, the weight pressed the gravel bed down by a full foot, a situation that was expected by the designers.

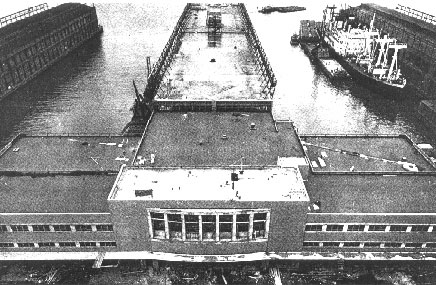

Now 146-foot long girders, 11 feet tall and two feet wide, were laid crosswise over caissons 2 and 3, forming the base for the floor of the pier. The girders extended 33 feet wider on each side than the boxes themselves. As weight was added by construction, the caissons were gradually pumped out. Ultimately the buoyancy of the caissons would support 90 percent of the weight of the finished pier.

All progressed well until March 26, 1953, when an explosion and fire killed two workers underneath the pier floor. Gasoline had leaked into the water and was ignited by a broken light bulb. The third worker survived but was in serious condition.

On Feb. 15, 1954, interior work in the headhouse and pier shed began, and finally, on Dec. 29, 1954, the new pier was opened by Mayor Wagner and Fire Commissioner Cavanagh, who had been chief of Marine and Aviation when work had started four years prior. The only glitch of the opening ceremony was the discovery that Cavanagh’s name had been misspelled as “Cavanaugh” on the dedication plaque. In the end, the innovative new pier cost $12 million.

Today, Pier 57 stands alone as the only pier to be built in New York City on floating concrete boxes. The experiment was a great success, but perhaps too expensive. In any event, by the end of the decade, the need for large passenger and freight piers had ended, as jet travel replaced the ocean liners and containerized shipping in New Jersey and Brooklyn made break-bulk cargo handling in Manhattan obsolete. Sometime after the W. R. Grace Company sold its shipping line in 1969, the pier was employed as a bus garage and maintenance facility by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. This use is expected to end at this end of this year, and the pier, now eligible for inclusion on the New York State Register of Historic Places, will begin a new life as a part of the emerging Hudson River Park.

Doswell based this article on numerous New York City newspaper articles from 1947 to 1954 compiled by Norman Brouwer