By Jeff Galloway

Volume 16 • Issue 33 | January 16 – 22, 2004

TALKING POINT

Considering on different memories at the W.T.C.

Let us begin by acknowledging that memory belongs primarily to the individual: the unique and personal remembrance of someone deeply loved, of shared lives, of unspeakable grief and longing. At the same time, we must acknowledge the extent to which the evolving process of memory also belongs to families and neighborhoods, communities and cities, even entire nations.

So begins the memorial jury’s statement introducing the memorial design crafted by Michael Arad and Peter Walker. How better to explain the enormous difficulty with which advocates for Lower Manhattan residents and advocates for family members have attempted to reconcile their disparate visions for the memorial? Yet, if initial press reports are any guide, it appears that the chosen memorial design may be bridging that gap of differing individual and collective memories.

In introducing the design this week, memorial jury chairperson, Vartan Gregorian, noted that the memorial process began with the candlelight vigils in places like Union Square. The image of these candlelight vigils, triggered a different set of memories for me – a series of images etched in the soul: walking on Warren St. with my wife that beautiful, sunny morning as we had just left our kids at P.S. 234, when we heard a screeching noise over our heads, then “BOOM,” a hole and fire in the North Tower; the white tablecloth being waived out of Windows on the World, a futile cry for help; the fireball coming right at us, now back in front of P.S. 234, when the second plane hit; the children crying in my daughter’s 5th grade class, as the teacher hugged them, crying too, while other 10-year-olds pulled down the shades so that they wouldn’t have to look at the Towers on fire; my then-3rd grader son asking me why the people were jumping as we walked home to Battery Park City to retrieve our dog. My son screaming, “it’s falling!” as we stood only 200 yards from the South Tower, followed by our family’s mad dash to try to escape the roaring avalanche of fiery debris rushing at us at a speed far faster than we could run. The total blackness, as we fell to the ground, the eerie silence as the cloud enveloped us, the expectation that we would all be dead as the anticipated heat and poison had its effect. The exuberant feeling, “we’re alive!” when we realized that the cloud was not fire, and apparently not poison either.

The acute, but zigzag, memories of horror and joy then shift to memories of numbness: the cattle-like procession of escape toward Battery Park; the silence, hours later, on the evacuation ferry to Jersey City, as we stared back at the smoke and the hole in our familiar skyline, wondering if our home was on fire, but not really caring, because we were together and alive. Our continued numbness as we saw, but could neither feel or even comprehend, the candlelight vigils sprouting around us in our temporary New Jersey refuge, our thoughts instead being, “what’s happened to our neighbors, what’s happened to our home”; the frustrating, yet somehow therapeutic attempts to run the barricades at Pier 40, as we tried unsuccessfully to get to our homes, but at least in the process meeting up with friends and neighbors and seeing them still alive. Sparks of hope flitter, though, as when Bob Townley, vowing to keep Downtown after-school programs running but acknowledging that the overwhelming tragedy had tempted him to call it quits, declares instead that “the King does not go down without a fight.” The numbness returning, with the candlelight vigils everywhere we looked, not just in Union Square, but in nooks and crannies throughout the city. The feeling of anger as the rest of the city “got back to normal,” while we were living like Bosnian refugees, trudging through caked W.T.C. muddy debris with whatever possessions from our home we could carry on our backs, quickly followed by feelings of guilt, as we realized that we were at least alive, while other families were posting pictures of their loved ones around town, asking the “have you seen this person?” question that by that time could have only one terrible answer. The oddly dreamlike quality it all had for us, as we drifted through weeks and then months of homelessness. The pure joy when we moved back home on the eve of Christmas, even though our home was in the middle of a war zone. The determination that we will build back our neighborhood, newly strengthened by the tremendous sense of community that the new adversity had brought to Lower Manhattan.

Change the names, change the details a little, and you have the stories of thousands of other Lower Manhattan residents and survivors of Sept. 11. As terrible as these stories are, none of us would trade them for the stories of the families who lost a loved one that day. Oddly, I would not even trade our story for those of my fellow New Yorkers, whose lives “went back to normal” within days of Sept. 11. I certainly wouldn’t trade my story for those who were not in New York that day. This is our home, terrorist target or not.

President Kennedy was shot when I was in 4th grade. Even at that young age, I could tell that the world changed. It signaled a loss of innocence, a recognition that we, as individuals, and we, as a country, were vulnerable. My father told me then that that day would be like Pearl Harbor Day had been for his generation. Even today, all Americans over the age of 47 can describe exactly where they were and what they were doing when Kennedy was shot; and any American over the age of 70 can tell you the same for Pearl Harbor Day. Sept. 11 is the new Pearl Harbor Day, the new “day that Kennedy was shot.” Its significance extends beyond America, however. It was witnessed live, on TV, all over the world, and it was instantly and nearly universally recognized as not just an attack on America, but an attack on a system of democratic and pluralistic values.

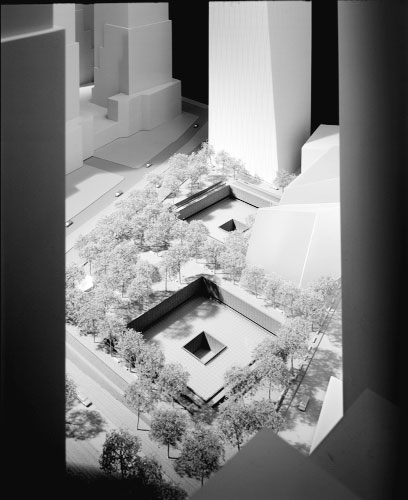

In our typically New York-myopic view, when it comes to Sept. 11, there are three groups of people, those who lost a loved one; those who witnessed and survived; and those who saw it on TV. These groups are hardly monolithic in their views of what Sept. 11 means, much less in their views of what the memorial should look like or speak to. But these groups, at the gross level, clearly will have different “personal remembrances” of that day and its aftermath. The power of Michael Arad’s and Peter Walker’s Memorial design is that it has the potential to speak to a range of memories and aspirations, from the family members’ desire to be able to mourn at the very bedrock of the footprints; to the survivors/residents’ vision of hope and neighborhood rebirth symbolized by the manner in which the memorial’s green plaza weaves itself to, through and beyond the site; to the general, and even international, public’s expectation that by coming to the site, one will have a chance to feel Sept. 11’s meaning through physical connection.

The memorial design revealed this week will surely grow and change, and will surely generate continued debate as the details are finalized, but it offers the prospect, for the first time in a very long time, that the widely ranging “personal remembrances” of all those affected by Sept. 11 can indeed be reconciled within a single Memorial.

Jeff Galloway is a member of Community Board 1’s World Trade Center Committee, and one of the primary writers of C.B.1’s memorial resolution, which recommended that the jury consider Reflecting Absence or three other possible memorial designs. The views expressed are his own.

Reader Services