By Julie Shapiro

As a recent transplant to New York City, I’ve often heard stories about what the city was like just after 9/11 — that the pace slowed, strangers helped each other and people didn’t push and elbow on the streets and subways. I wondered, having never been in the city on any of the subsequent anniversaries, if some of that consideration would return last Thursday, seven years after the attacks.

It didn’t take long to get my answer, and the answer was both a jolt and a relief.

As I walked to the subway Thursday morning, shopkeepers swept garbage from the sidewalks in front of their stores, joggers bounded past mothers pushing strollers and deliverymen on bikes wove in and out of traffic. Just as I started to cross Delancey St., a traffic agent waved a cement truck through the intersection, where he passed inches from me and a group of pedestrians. One angry woman gave the traffic agent the finger, then extended the gesture to the cement truck and much of the block. “You crazy?” she yelled.

I finished crossing the street with a smile on my face: This was New York, business as usual.

Near City Hall, the scene was similar: Cars honked, tourists wandered and women in heels and business suits sipped Starbucks and spoke hurriedly into cell phones. The atmosphere was so normal that I almost wondered if this was not the anniversary of 9/11 at all.

But as I started talking to the people who were sitting on benches in City Hall Park, the presence of the anniversary grew clearer. Normally reticent New Yorkers, who don’t usually warm to the sight of my reporter’s notebook, seemed to have been waiting for the opportunity to talk — about where they were, what they remembered and what the day means now, seven years later. Once they started talking, some didn’t want to stop.

Most embraced the apparent normalcy of the day as a sign of recovery.

“I’m glad,” said Sam Wagner, 48, a Tribeca artist who was in the park with his poodle, Shona. “It shows people are willing to move on, and that’s really important.”

Wagner, who is gay, said he refused to stay silent about his sexuality back when the country was less welcoming, and he similarly refused to feel afraid when terrorists attacked New York.

“Fear is what the terrorists wanted,” Wagner said. “I’m going to be defiant toward them. It made me more courageous. New York is a very strong people.”

Just outside of City Hall Park, police officer John Jay, 36, leaned against a fence, looking toward the Brooklyn Bridge. Jay joined the N.Y.P.D. in 2004, partly because of 9/11. “You have to do something,” he told me.

But the day-to-day life of his job is less than inspiring, he said. Being posted Downtown is “a pain in the balls” because tourists constantly ask him for directions. And Jay was sad to see everyone treating the anniversary like an ordinary day.

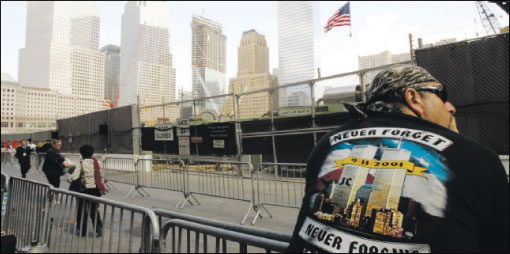

“Everyone forgot about it already,” he said. “They should never forget.”

The sky was clear and blue Thursday morning, just as it was seven years earlier.

A 63-year-old man in a suit and sunglasses pointed out the weather to me, noting the similarity.

“It’s slightly eerie,” said the man, who was sitting on a bench in City Hall Park, early for a business lunch. “It’s a curious day. It’s a little rougher than usual to concentrate.”

The man, who owns a publishing company Downtown but did not want to give his name, told me that the anniversary is even harder for his wife, who was working on the 90th floor of Tower 2 on 9/11. She made it out of the building alive and found her husband on the chaotic streets of Lower Manhattan. But many of her colleagues at Fiduciary Trust did not get out in time, and her company, now based in Rockefeller Center, held a memorial service for the anniversary Thursday morning.

The sky clouded over toward lunchtime, but local workers still filled the park to eat lunch, just like they do every day.

One of those workers was Leah Gooch, 23, an elementary art teacher at the Ross School. I asked if her students were upset by the anniversary, and she pointed out that many of her first graders weren’t even born yet.

“They weren’t here when it happened — it’s like us getting sad about Pearl Harbor,” Gooch said. “If we’re sad, we’re sad for the people we love who were affected.”

Gooch, who moved to Murray Hill six weeks ago, said that while New Yorkers should commemorate 9/11, they should also be aware of far worse tragedies that are going on around the world.

“We’re in a war and people just go about their lives every day,” she said.

As I was leaving the park I met Luis Velez, 48, a train service supervisor for the M.T.A. and a member of the Hazmat unit, formed after 9/11. He has worked for the M.T.A. since 1990, but he had the day off seven years ago and watched the attacks on TV.

“I thought, ‘This would never happen in the United States,’” he remembered. “I thought, ‘This is New York — we can overcome everything. They’ll go in there, save everyone, put out the fire, fix the building.’ As the tower started collapsing, I just opened my mouth. I could not believe it.”

Velez left his apartment that day and heard silence in the streets of the Bronx. No one honked their horns. People walked slowly, their heads down.

“It looked like a ghost town,” Velez said.

Velez told me it was his continuing sense of disbelief about the attacks that led him to volunteer to work at ground zero. The Saturday after 9/11, he walked through debris-strewn subway tunnels near the site, investigating the extent of the damage. Outside, Velez saw smashed buildings and the smoking pile, and he understood for the first time that 9/11 was real.

Julie@DowntownExpress.com