By Mark L. Kimmey

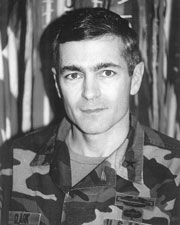

Although I served under then Brigadier General Clark at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California, thirteen years ago, I can’t say that I know the man personally. However, as is usually the case with interesting leaders, he has been the subject of much conversation over the past decade-plus, as I have constantly met others who worked for, with, or sometimes against him. From these conversations, I have constructed an understanding of a man who is sometimes brilliant, often demanding, and charismatic as hell. In short, all the things we want in an Army general. Whether those qualities would translate effectively into a successful presidency is open to debate.

Clark is a sharp, imaginative and energetic man who most of us in uniform fully expected to become Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The fact that he did not ascend to that position, choosing to retire after his poor treatment by the Clinton administration, was a shock to many of us in uniform, whether we wore it full- or part-time. I know that many were happy to see Clark’s departure: although everyone I’ve talked to about the man recognizes his strengths, there was a common caveat, “…but I’m not sure how far I trust him.”

The first time I heard someone voice that concern I was surprised. My encounters with Clark at the N.T.C. had generally been positive. For several years I ran a program supporting West Point recruiters in Southern California, inviting them and their candidates — mostly high school juniors and seniors — to Fort Irwin to see soldiers in action a couple of times each year. One of the big problems we had in those days was that candidates would receive nominations to more than one service academy. Then the Air Force or the Navy would present an air show at one of their many bases in the region and we’d lose the candidate’s interest. Fort Irwin is the only real Army installation in Southern California and it’s tucked away in the middle of the Mojave Desert, far from casual view. As the senior “grad” on post, Clark had a personal interest in the program and provided recommendations on how to improve it. In particular, he was concerned that the candidates have the opportunity to talk with a wide variety of graduates assigned to the post, both in terms of rank and specialty. As the commanding general, Clark could also influence those graduates to attend the informal question-and-answer sessions with which we closed out a day’s visit.

Clark also deserves credit for figuring out how to defeat the extensive Iraqi defense systems used during the first Gulf War, which was critical to our success in ejecting Iraq from Kuwait in 1991. He personally directed construction of a full-scale battle position at Fort Irwin, manned it with opposing force soldiers using laser-tag style training devices, and then tried to apply current American doctrine to defeat it. When we failed, he guided the re-writing of that doctrine until we found a solution. This solution was then videotaped and sent to U.S. forces preparing to execute Operation Desert Storm. The results are history.

Despite his obvious competence, the common thread as I talked to more people — mostly Army officers — about him was a feeling that if you could help him, he would use you; if you couldn’t, then you might as well not exist

Clark has a reputation for excellence, a penchant for micro-management, and a smooth but sometimes inflexible demeanor. I know that during his tenure as a White House fellow, he was not a popular figure among several influential congressional staffers, but maybe that’s not a ding. I’ve heard his West Point classmates refer to him as “The Prince of Darkness,” though that may be from jealousy as much as anything else: Clark was first in his class at the Academy, and had been identified by staff and student body as a fast mover even then. Regardless, Clark has a well-deserved reputation as someone who makes things happen. You can bet he wouldn’t be taking month-long vacations, working or otherwise, while in office.

I think the most interesting question about Clark is simply, “Why does he want to be president?” In trying to pin down an answer, I visited Clark’s Web site, where I read his vision statement. While it reads well, I’m not sure that it sets any new milestones for American foreign or domestic policy: vanilla, in other words. I think the real answer to the question is simple: ambition. It is my opinion that with his military career cut short just when the brass ring of the chairmanship was within reach, Clark was left with the frustration of unrealized ambition. I can only imagine him looking around at what might have seemed the end of a career of national service and asking himself, “What’s next?” The answer to that is his aspiration to the presidency.

Should we or should we not vote Wesley Clark to the presidency? I have no doubt that if elected he would bring all the energy, competence and professionalism of his military career to that office. The fact is that he is fully qualified for the job. Whether he is BEST-qualified will have to be decided by the voters. We could do a lot worse than Wesley Clark: it is up to the voters to decide whether we can do better.

Mark L. Kimmey is a Battery Park City resident and Army Reservist on duty in the Arabian Gulf. The views expressed are his own and do not represent the United States Army.

Reader Services