So many photographs (usually of ordinary people doing ordinary things at ordinary places) are posted onto social media nowadays, but how many of those photographs will actually survive in time if there are no physical copies? And if the photos do survive, might they actually seem shocking to future generations? This is a theme in two plays currently running in New York – both excellent, yet both very different.

In Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ entertaining dark comedy “Appropriate,” three adult siblings, who are visiting their family’s decaying plantation home in Arkansas before it is sold off, discover an album of photographs that appear to depict African Americans being subjected to horrible physical abuse, which raises questions about where they came from, what this means about their late father (who apparently collected them), and what they should do about them, including whether to destroy them, donate them to a museum or even sell them.

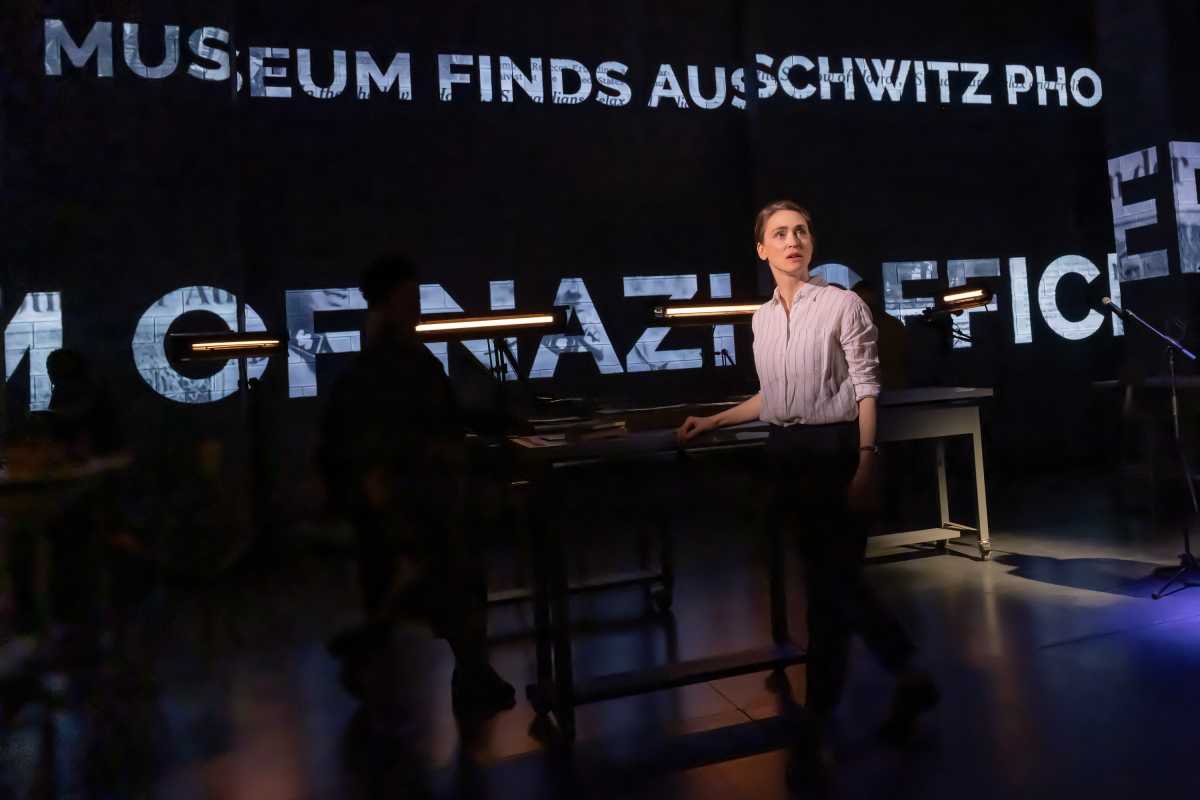

On the other hand, “Here There Are Blueberries,” a new docudrama conceived, directed, and co-written by Moisés Kaufman of the Tectonic Theater Project (“The Laramie Project”), which is now receiving its Off-Broadway premiere at New York Theatre Workshop, dramatizes what actually happened in 2007 when an archivist at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum came upon a mysterious album of Nazi officers and administrative employees relaxing and engaging in recreational activities while stationed at Auschwitz. It is now known as the Höcker Album (named after Karl Höcker, the Nazi officer who is believed to have made the album).

The 90-minute play (which was recently named as a finalist for the 2024 Pulitzer Prize for Drama) is not unlike an unusually engrossing lecture and well-designed Powerpoint presentation (in which the original images from the album are projected onto various surfaces) combined with short scenes in which the ensemble cast (led by Elizabeth Stahlmann and Kathleen Chalfant) portrays museum employees, historical figures, and a few family members.

The questions raised by the photographs are numerous and complicated. In addition to determining the basic facts over who and what is being shown in them, the employees question what the museum should do with the photographs (would exhibiting it serve to glorify the victimizers?) and what the photographs reveal about people who participate in crimes against humanity (who otherwise appear as happy teens or bureaucrats who eat blueberries, sing songs, enjoy the weather, and celebrate the holidays).

The photographs in the Höcker Album do not depict any of the camp’s prisoners – such that it might be mistaken for an ordinary family scrapbook. It serves as a disturbing counterpoint to the Lili Jacob Album, which was discovered upon the liberation of Auschwitz and depicts Jews as they arrived at the camp on the trains and were selected for either hard labor or immediate murder.

“Here There Are Blueberries” shares a lot in common with the musical “Cabaret,” which is currently being revived on Broadway and which is set in Weimar Germany and suggests how the Nazis took power through a weary population that either celebrated Hitler or passively failed to take action against the new regime. Like “Cabaret,” “Here There Are Blueberries” is meant to serve as a warning shot that “it can happen here” and that it is not so difficult to become an accessory to a larger, very dangerous movement that one day will cause bewilderment and shame.

New York Theatre Workshop, 79 East 4th St., nytw.org. Through June 30.