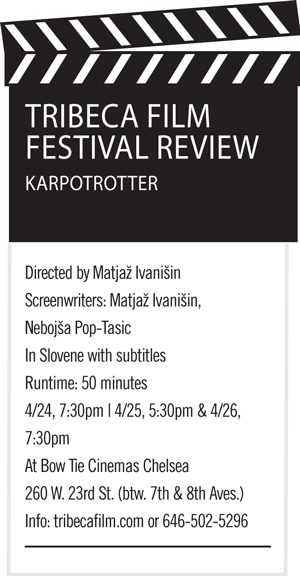

BY SCOTT STIFFLER | A bygone journey down a straight road “too lazy for turns” comes full circle, in this agreeably meandering homage to the early work of Karpo Godina — an important contributor to the “Black Wave” of Yugoslavian filmmaking.

BY SCOTT STIFFLER | A bygone journey down a straight road “too lazy for turns” comes full circle, in this agreeably meandering homage to the early work of Karpo Godina — an important contributor to the “Black Wave” of Yugoslavian filmmaking.

In 1968, 25-year-old Godina is sitting in his apartment, presumably minding his own business — when fate literally comes calling. “I don’t know anything about directing,” the unidentified man on the other end of the phone says, “you don’t know how to handle a camera, so, together, we could create something huge.”

‘Karpotrotter’ finds its own way by retracing the steps of another

So K.G. hightails it from Ljubljana (then part of Yugoslavia, now the capital of Slovenia), spending a few “pleasant and exciting” months working a cinematography gig whose down time is filled with making love, eating “a ton of potatoes” and soaking his brain at the local pub. When he leaves, the camera goes with him, to document his aimless road trip throughout the ethnically diverse Vojvodina region.

Decades later, only fragments of the resulting film survive. Called “Imam jednu kuću,” which translates into “I Have a House,” the title comes from Godina’s vow to “make a house that will dwell within me” out of the stoic people and the shifting rivers, trees, wind and earth captured during his travels.

Or so we’re led to believe. It’s hard to tell, since we’re never quite sure if that vow, heard in the form of a voice-over, is a direct quote, the product of informed speculation or a convenient bit of wishful thinking. Just as iffy is whether, at any given moment, we’re watching Godina’s original Super 8 footage or contemporary portraits of the Slovinic landscape.

Best not to labor over making that distinction, since the five small villages revisited by director Matjaž Ivanišin don’t seem to have experienced a single demographic shift or aesthetic upgrade over the past four decades. This gives the work of both filmmakers a seamless quality, although not necessarily a timeless one. Contemporary interviews with veterans of Godina’s first pass through town add real dimension to the static, largely dour group tableaus that represent the lion’s share of what remains from “I Have a House.”

We learn that Ficko, the imposing accordion player belting out a Rusyn folk song, was a veterinarian whose passion for boxing obligated you to fall down when greeted with an affectionate punch (an entire church choir once played along). Winnetou, standing to the right of his village’s muddy, horse-filled street while strumming the guitar and crooning in Romani, is remembered as a mentally unstable young man whose physical outbursts were followed by self-imposed exiles, then sheepish offers of eye-for-an-eye amends. Both men are long dead — victims of unforgiving disease and brutal beatings, respectively.

Ivanišin has an interesting technique for these then-and-now perspectives, which is to forego English translations of the lyrics in favor of running narrative commentary over the performances. With no subtitles to go on, it’s impossible to tell if they’re singing about life’s joy or its futility. Only those who speak the language know for sure, which keeps the rest of us at arm’s length.

- Photo by Marko Brdar

Same as it ever was: Velika mala vas, one of five villages getting the then and now treatment.

This calls into question the extent to which an outsider can take away anything other than fleeting moments of pleasure and slivers of truth as they breeze in and out of town. Godina seems to have had the right answer, given that he’s remembered by contemporary villagers as an amiable and endearing type who spent just as much time drinking with the adults and playing soccer with the kids as he did composing sober portraits of the townsfolk.

One gets the sense that Ivanišin must be operating behind the scenes in a similar manner, considering the intimate details he’s able to draw out of people who come across hospitable but guarded. In this respect, both “Karpotrotter” and “I Have a House” are in possession of a solid foundation that’s built to last.