BY DENNIS LYNCH | Chelsea’s Printed Matter bookstore is running a career-spanning exhibit of works of one of the Lower East Side’s fiercest and certainly one of its least-known antiestablishment artists, Richard Tyler.

“The Schizophrenic Bomb: Richard Tyler and the Uranian Press” examines Tyler’s work as an artist, thinker and co-founder of the Uranian Phalanstery, a spiritual and pseudo-mystic art collective that sought to merge life with art and challenge societal norms.

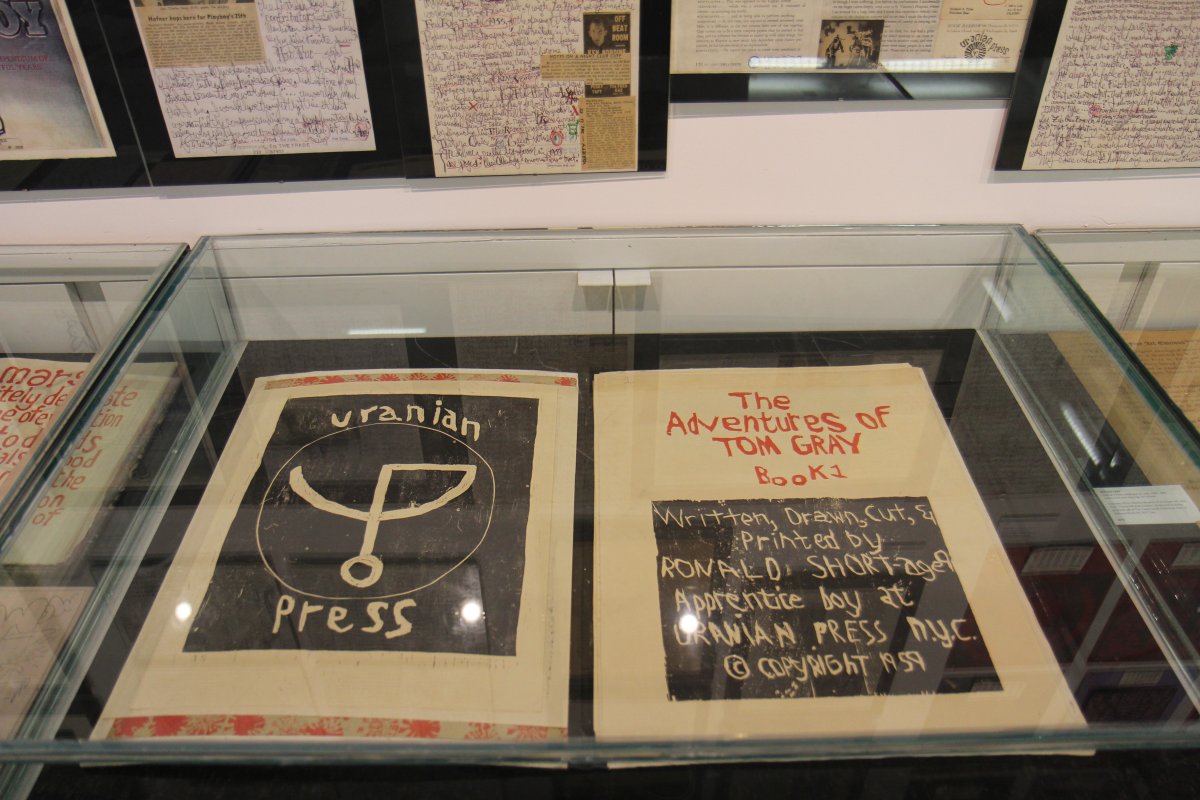

The exhibit takes its name from one of Tyler’s many hand-pressed treatises, which in this case addressed nuclear holocaust. As he did with many of his writings, Tyler expounds his worldview in the “The Schizophrenic Bomb” with epic, proselytizing language conveyed in a highly unique visual style.

The exhibit spans his entire career, from his earliest works in the mid-1950s, to his founding works for the Phalanstery in 1974, to his last work detailing his battle with cancer before his death in 1983.

Tyler got his start as a woodblock-print artist and was a “star” at his Chicago art school — good enough to have his early works included in Smithsonian collections, according to Max Schumann, the executive director of Printed Matter, at 231 11th Ave., at W. 26th St. He arrived in New York in the late ’50s with his wife and fellow artist, Dorothea Baer, worked as a commercial graphic artist, including for Playboy magazine, and helped found the famous Judson Gallery at Judson Memorial Church, on Washington Square South.

Even though he was deeply involved in the art scene at the time, Tyler never aspired to ascend in the fine-art world, according to Schumann. The Printed Matter owner first met Tyler as a family friend of his father, Peter Schumann, who founded Bread and Puppet Theater on the Lower East Side in 1963.

Tyler’s disinterest in fame is perhaps why he’s not more well known, Schumann said.

“Very few people knew about Richard Tyler,” he said. “But the people that did know about him, he had a big impact on. He was a real outsider, as he had no interest in fame and fortune with galleries and stuff like that.”

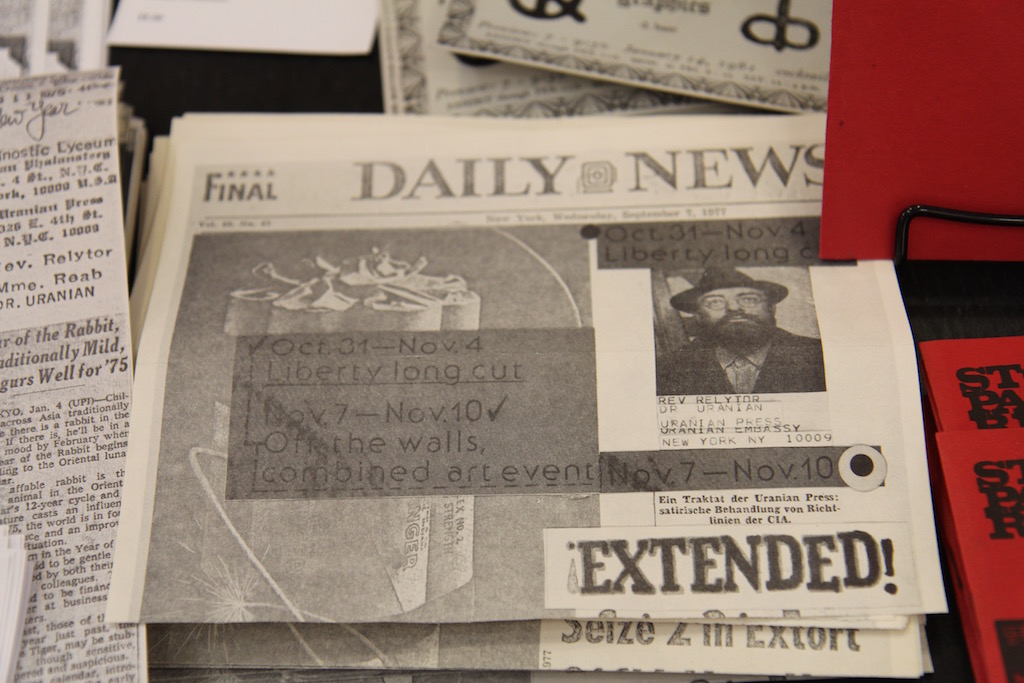

The exhibit includes almost everything the still-functioning Phalanstery has kept of Tyler’s, including his signature pushcart, from which he would sell his and others’ artworks and treatises. Tyler could be seen wheeling the cart each day from his East Village basement to Judson Church to sell his wares. The group was based in two adjacent buildings on E. Fourth St. near Avenue D, buying them in 1974.

The younger Schumann admits that he is personally “still trying to figure out” Tyler’s philosophy and work. Tyler was a “madman” and a “violent freak in many ways,” he said, yet also a person with charisma, which attracted artists to his little arts collective.

He was dedicated to D.I.Y., doing all his pressing and printing in-house. The artist often hired young neighborhood kids to teach them pressing methods and to help press Uranian Phalanstery materials.

Tyler, who spent time in Japan immediately after World War II, was strongly influenced by the imagery and philosophies of astrology, as well as Eastern religions. He incorporated those themes in all of his works, long before the “New Age” movement exploded in Western culture. Tyler’s interpretations were noticeably darker and more mystical than the themes in that later movement, Schumann noted.

“It’s totally not hippie-dippie New Age,” he said. “There’s this sort of dark, death current that runs from the very beginning of his work to the end of it.”

Tyler put his offbeat creations on his body, too. He ran an illegal D.I.Y. tattoo parlor for Phalanstery members, inking himself and others with the symbols that adorned his pamphlets, the walls of his apartment and his collages. That earned him an interview and feature published not long after his death in Ed Hardy’s Tattootime magazine in 1983. If you want to get his philosophy from the horse’s mouth, that’s the interview to read. It’s available on the Uranian Phalanstery Facebook page.

Tyler and the collective also regularly took LSD and other psychedelics as a mode of “controlled schizophrenia, helping to facilitate entry into nonmaterial realms.” Like acid-dropping Lower East Side gardener Adam Purple, who sometimes called himself Rev Les Ego, Tyler similarly also went by Rev Relytor. (Like Tyler, Purple also distributed his own fliers, though from a bicycle not a pushcart.)

Schumann hopes that people will walk away with a new appreciation for Tyler and his collective’s works. Tyler was a man “whose life was really his art practice,” explained Schumann, calling him almost a “case study” in that regard.

“It’s the mash-up and the art-life practice,” he said, “where art, death, creativity, community, a lifestyle of living outside the system, and not only not being engaged or aspiring to high art or the institutions of arts — just completely not recognizing the values. So, it’s a refusal of the culture values that the rest of us are working within. He was a real renegade and anti-authoritarian, so I think that’s an interesting model. Someone who, they aren’t pissed because they aren’t in it, they just totally don’t give a s—. It doesn’t register as anything meaningful or important to be in a gallery.”

But now Tyler’s work is in a gallery. The walls feature blown-up photos of what his basement studio at 326 E. Fourth St. looked like. Because the two East Village brick buildings were in deteriorating condition, the Uranian Phalanstery relocated Uptown in 2010 to Hamilton Heights, where it continues today.

Printed Matter, which specializes in artists’ books and small-press publications, also started out Downtown, in Tribeca in 1976, and after a 20-year stint in Soho on Wooster St., moved to Chelsea in 2001 and to its current location in 2015.

The exhibit will be on view at Printed Matter through Sun., April 16. For more information, visit www.printedmatter.org .