By Davida Singer

Staying power is a prime attribute of writer/performance artist Deb Margolin. Since co-founding the acclaimed downtown performance group, Split Britches in 1979, Margolin has been a consistent force in avant-garde theater throughout the U.S. and abroad. With seven major solo shows under her belt, it’s not surprising she also nailed an Obie for Sustained Excellence of Performance in 2001.

Margolin currently lives with her two children in New Jersey and teaches at Yale, but her newest work, “Three Seconds in the Key,” has just opened for a month’s run at the Baruch Performing Arts Center, and she’s psyched to be back on the boards.

DS: Your play’s title refers to basketball. Can you elaborate?

DM: “Three Seconds in the Key” began in 2000. I had just been through chemo for Hodgkins – cancer of the lymph system. My son was 8, and we relied on watching basketball at that time to get through. I borrowed the bodies of these players. It was a very dark time for me. Being poisoned affects the spirit, and I did not know how to go on, but I promised my son I would make theater out of this. One day I just sat down and wrote and wrote and wrote – about this woman and her son watching basketball. It’s a comedy/drama and obviously autobiographical.

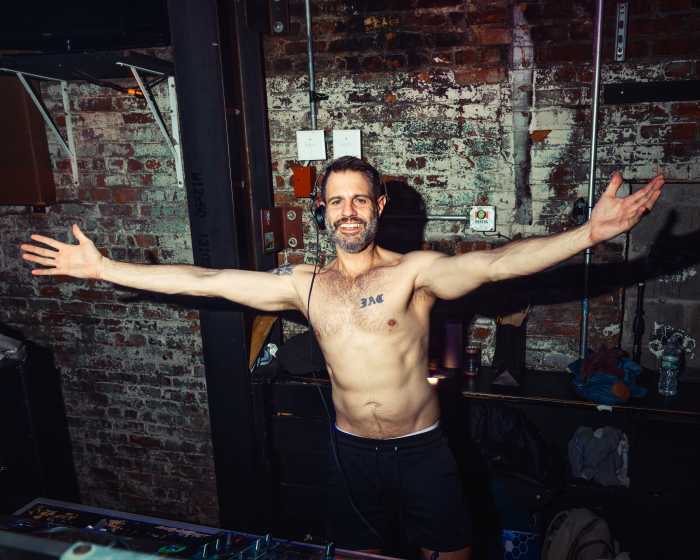

DS: One of the Knicks basketball team members comes out of the T.V. and into the mother’s living room?

DM: Yes, a sexy player comes into her life to put her back in her body. Illness robs you of sexuality, and half of her hair was missing. He’s sent to her because of his own mistakes. There’s no great love between them, but the arc of the play is some kind of redemption for each. For her, it’s to be back in the body. For him, it’s to be back in the spirit. So they help each other. The son is about constancy – how his need keeps her going. And the constant ache of loving on that level is what the play deals with.

DS: Where was “Three Seconds in the Key” first produced?

DM: It was originally done in 2001 at P.S. 122 as a performance piece, and I was in it. Lee Gundersheimer directed, and I actually played ball with NYU’s team, because I also taught there. Then there was a workshop at the Public, and it was picked up by Susan Bernfield of New Georges for this incarnation. I’m not in it, and it’s undergone a lot of honing and graceful revision. The arcs of all 3 characters are better developed, and the mother and the player have a daringly long look at each other now. I believe you go to theater for the revelatory aspect, to stare at people, at humanity. This play offers deeper opportunities for that.

DS: What about its essence?

DM: It’s about different kinds of love-of body, child, basketball, this life. There’s also a sense of breaking down barriers here, because it looks at the relationship between Blacks and Jews. Also, that illness is not a betrayal but an aria. Language fails and that’s why it’s so gorgeous. It points to silence in the most articulate way. Theater and poetry both have that, and this play is very poetic.

DS: Would you call the show’s tech ‘poetic’ as well?

DM: I would. Alex(andra) Aron is a tech queen. She’s very fluent in this. The sound design is fantastic, complete with stadium noise, and a feel that the audience is sitting courtside. The backboard of the hoop actually lights up like Foxwood, so there’s an elevated sense of environment.

DS: And is there added relevance for this new production?

DM: Definitely. For 8 weeks after 9/11, everyone was living like I was- with mortality in our face-until denial replaced it. This play peels away that denial. It’s my way of saying, ‘Could we just take a moment and look at this, the exquisiteness of living.’