BY DUNCAN OSBORNE | While some recent press reports claimed syphilis is surging among gay and bisexual men in Chelsea, the higher case rate in that neighborhood has existed for roughly eight years and shows no signs of declining.

“From 2012 to 2014, there’s been an increase,” said Dr. Sue Blank, who heads the sexually transmitted disease unit at the city’s health department, during an April 22 meeting at the LGBT Community Center. “It’s in the context of an ongoing increase.”

The city saw roughly 1,300 primary and secondary syphilis cases among men in 2014. There were 1,167 such cases in 2013 and 996 in 2012. The current higher rate of cases per 100,000 population began in 2007, when the health department reported 927 syphilis cases compared to 578 cases in 2006. Syphilis cases went from 621 in 2004 to 616 in 2005. The increase is attributable to new infections among gay and bisexual men.

“The contribution among women is really small,” Blank said.

“That’s been true for many years.”

Chelsea/Clinton and the West Vill-age are the city neighborhoods with the highest syphilis case rates among men. In 2014, there were 175 male syphilis cases per 100,000 population in those neighborhoods. There were 32 male syphilis cases per 100,000 population citywide and 65 male syphilis cases per 100,000 population in Manhattan in 2014. Chelsea/ Clinton and the West Village also have high rates of hepatitis B and C and other sexually transmitted diseases, and have consistently had the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the city.

Since 2011, most of the syphilis cases among men have been diagnosed in men aged 20 to 39, while men aged 40 to 49 have seen declines in syphilis. While increases since 2011 in syphilis cases per 100,000 population were comparable among African-American, Latino, white, and Asian men, African-American men began that period at a higher rate and ended at a higher rate. In 2014, Manhattan contributed 38 percent of the roughly 1,300 male syphilis cases followed by Brooklyn at 26 percent, the Bronx at 21 percent, Queens at 14 percent, and Staten Island at one percent.

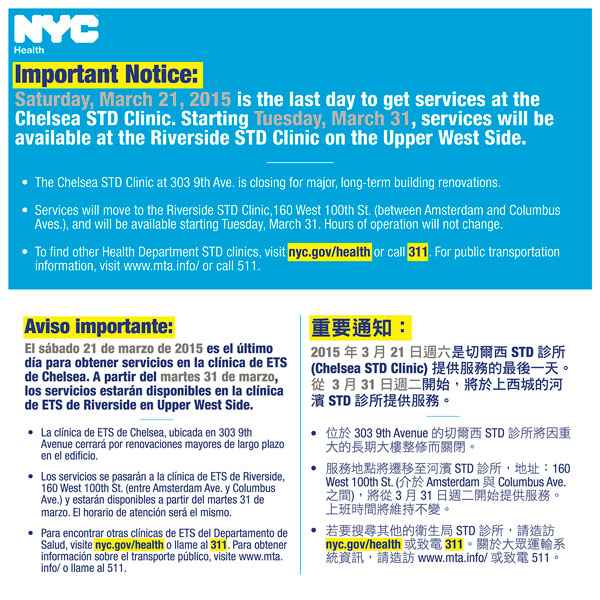

The ongoing syphilis problem may be made worse by the closing of the city’s sexually transmitted disease clinic in Chelsea. The renovation of that location is expected to take two to three years, though Blank said that work should be completed in closer to two years.

“We did not take that decision lightly, but there was no easy answer,” Blank said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Stonewall Democratic Club of New York City. “We still have other clinics that are a subway ride away.”

In 2013, the Chelsea clinic had more visits, at 21,148, than any of the city’s other eight sexually transmitted disease clinics and contributed 23.8 percent of all visits to the nine clinics. The Chelsea clinic also led city clinics in visits in 2012.

Blank said that the other city clinics, and the Riverside clinic in particular, were expected to take the visits previously handled in Chelsea. The Riverside clinic had just under 5,000 visits per year in 2012 and 2013, and contributed five percent of all visits in each of those years. The city is also expecting private providers to take up the slack.

“Although we don’t have brick and mortar services in Chelsea at this time, we are funding services in the neighborhood,” Blank said. She could not say if the city was providing more cash to nearby providers, such as the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, but did say, “We have provided more resources.”

At the meeting, Donnie Roberts, Callen-Lorde’s senior director of Development and Communications, said his agency has added “105 new sexual health appointments” every week in an effort to cover some of the visits that will no longer happen at the city’s Chelsea clinic.

Some AIDS activists are voicing concern about closing the Chelsea clinic because that could impact the plan to end AIDS, which envisions reducing new annual HIV infections from the current roughly 3,000 to 750 a year by 2020. Some of the clients at the city’s sexually transmitted disease clinics would be candidates for the biomedical interventions, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), which will be used to reduce new HIV infections.

“We’re trying to get more services for testing in the gay community and this move by the department of health is in completely the other direction,” Luis Santiago, a member of ACT UP New York, told our sister publication, Gay City News.