By Jerry Tallmer

Scenes that never made it into ‘Streetcar’ and ‘A View From the Bridge’ the early version

Now hear this.

It is the morning after. Blanche and Stanley are groggily awakened from their bed of passion by a telephone that rings seven or eight times. Stanley staggers up, listens, grunts: “Yeah? Good.” Blanche asks: “What was it?” and Stanley Kowalski says: “I have a girl, a daughter.” His shoulders are full of lacerations, fingernail scratches.

Blanche catches her breath, then says: “How very, very unfortunate. Poor little girl!” He shoves his wife’s sister roughly away. “Christ!” he says, and Blanche Du Bois, laughing hysterically, gets out these words:

“Remember, you took me. It wasn’t I that took you. So if you got somewhat more than you bargained for, Mr. Kowalski . . . If you hadn’t suspected a lady could be so awful . . . violent . . . could give such a wild performance when aroused . . . Try to remember the way it started, not I but you, putting dynamite under the tea kettle. Ha, ha!”

What price now the kindness of strangers? Who needs one of the single greatest poetic lines and multiple depths of sensitivity in all theater, certainly all American theater?

Not this Blanche, this Stanley. Who by the way was originally named Ralph, in various early stabs at scenes of what would become — mercifully, without those scenes — a play by Tennessee Williams called “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

This coming Monday, February 23, the ninth season of Susan Charlotte’s “Food for Thought” lunch-hour theater at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park South gets under way at half past noon with sandwiches and “Roads Not Taken,” a reading under the direction of Melvin Bernhardt of six rare, unpublished, unproduced fragments — starts toward “Streetcar” — from which, as researcher-narrator Dan Isaac puts it, “you can learn one true thing: How many false starts are involved in the making of a masterpiece.”

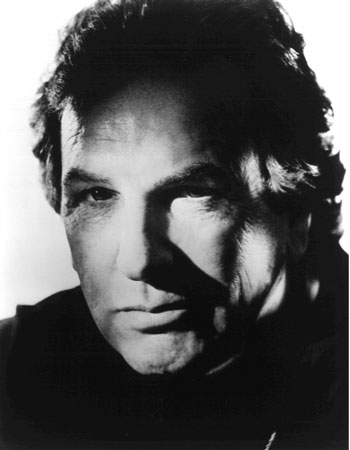

Robert Cuccioli is the reading’s Stanley, John Doman its Mitch, Margaret Colin its Blanche.

Two days later, Wednesday, February 25, same time, same place, a little-known one-act early version of Arthur Miller’s “A View From the Bridge” gets a reading by Danny Aiello, Robert Lupone, and others under the direction of Austin Pendleton.

Isaac, who has devoted much of his own life to the life and works of Tennessee Williams, and who in 1984 and 1986 dug the existence of these pre-”Streetcar” fragments out of the card catalogues at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center in Austin, Texas, says “it is very hard to tell” exactly when they were written — “we can only speculate” — though a strong clue is provided by “one absolutely invaluable document,” a three-page letter Williams wrote to his sheltering agent, Audrey Wood, on March 23, 1945.

Which was three days before his 34th birthday and eight days before the New York opening of “The Glass Menagerie,” the play that would change his and our and everybody’s life.

Here is part of that letter:

“Dear Audrey . . . I have been buried in work the last week or so and am about 55 or 60 pages into the first draft of a play which I am trying to design for [Katherine] Cornell. At the moment it has four different titles, ‘The Moth,’ ‘The Poker Night,’ ‘The Primary Colors,’ or ‘Blanche’s Chair in the Moon.’ It is about two sisters, the remains of a fallen southern family. The younger, Stella, has accepted the situation, married beneath her socially, and moved to a southern city with her coarsely attractive, plebian mate. But Blanche . . . has remained at Belle Reve, the home place in ruins, and struggles for five years to maintain the old order. Though essentially decent and very delicate by nature, she has gone for protection to various men till her name is tarnished . . . She arrives broken by the failing struggle . . . and is at the mercy of the tough young husband, Ralph . . . ”

A couple of other titles the playwright put on these shards were “Electric Avenue” and, borrowed from T.S. Eliot, “Go, Said the Bird!” As for Mitch, Stanley’s poker and bowling buddy who’s attracted to Blanche, these early drafts had him as “Howdy” and “George” and “Eddie Zwadski” before he became Mitch.

One has to say it is pretty hard to envision a Howdy (Howdy-Doody?) in that terrible moment in “Streetcar” when he forces her face toward a light bulb to see how old she really is. One has further to say that all these false starts — lacking ambiguity, delicacy, grace, loss, or pain — are very false indeed to the great play that Williams gave us when he cut away all the dead roots and poison ivy.

“Yeah,” says Dan Isaac, “that’s the purpose of this whole piece. Though I do think there’s pain in some of these scenes.”

Isaac further thinks that the March 23, 1945, letter to Audrey Wood was, for Williams, “a kind of insurance policy against failure. If ‘Streetcar’ got blasted in New York, he still had something in the bank: ‘Look, ma, I’ve got a new play.’ Tennessee was always looking for a mother.”

Arthur Miller wasn’t looking for a mother. He was, thinks Austin Pendleton, looking for immortality, if reaching for Greek tragedy on the Brooklyn waterfront is a path to immortality. “A View From the Bridge” was spawned, as was “The Crucible,” by the red-baiting-and-squealing era of American political culture.

“Miller had three sources of interest here,” says Pendleton. “One, the business of informing. Two, he had just after the war gone to Italy, seen the poverty, seen young men and old men standing in line for jobs; then, walking around Brooklyn, had suddenly seen poverty and unemployment from the immigrants’ point of view.

“And the third thing, more famously, was his obsession with the question of tragedy. The Greeks. ‘Oedipus Rex,’ you know, is a one-act play, and when ‘A View From the Bridge’ was first done in the 1950s, it was as a one-act play on a double-bill with ‘A Memory of Two Mondays.’”

The version of “View From the Bridge” that gets read at the National Arts Club dates even before that.

“The dirty secret,” says Pendleton with some amusement, “is that they aren’t all that different” – – this early draft and the longer, fuller version that Peter Brook asked Miller put his hand to for a London production.

“What Miller did primarily was add some scenes; also take all the lines that were in verse and put them into prose. They’re still verse; it’s just the way the actors speak it. The key scenes are now more natural. The people are now more embedded in their daily lives. The action doesn’t seem as preordained.”

But it’s still tragedy.

Austin Pendleton is himself just back from London, having acted there in a movie called “Picadilly Jim.”

Meanwhile, Dan Isaac is still not forgiving himself for having missed, at age 14, in Chicago, the world’s first performances anywhere of “The Glass Menagerie,” with the great Laurette Taylor (some of us were luckier than Isaac). He does remember overhearing a girl in high school telling her circle of intimates: “There’s this play, it’s so sad, about this crippled girl . . . “

Blow out your candles, Laura.

Hey! There’s this other play, “Candles in the Sun,” Tennessee Williams’s first full-length work — a militant tragedy about a coal-mine strike in Alabama — that hasn’t been produced anywhere since the Mummers did it in St. Louis in 1937. Isaac is now editing it for publication. He has an eye on getting some of this “unknown Williams” into some Fringe Festival.

That’s what Fringes are for, yes? Answer the telephone, Stanley. And let’s get some mercurochrome on those scratches on your shoulders.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/business-finance/