By 2004, after some maturation of his own, Wyn Davies was ready. They tried it out at the launching of an Atlantic Theatre Festival in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, and subsequently at Stratford, to general acclaim. But then Leon Pownall died — leaving be

Current production percolating since 1985

Back in the days in which quality still meant something — whenever you could find it in what Communications Commissioner Newton Minow called “the vast Wasteland” of television — CBS had a weekly news-and-culture program called “Omnibus.” It was anchored, impeccably, by Alistair Cooke. And it was on “Omnibus,” one evening in November 1953, that the visage of Dylan Thomas appeared as we heard him delivering “Do not go gentle into that good night…,” his undying manifesto against death.

And as we heard his voice saying it, we saw his image get smaller and smaller and smaller — retreating, as it were, into the back of the television tube, and then, with the last words of the great poem — “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” — winking out entirely into the dark. The most powerful poet of the twentieth century had, in fact, died that week.

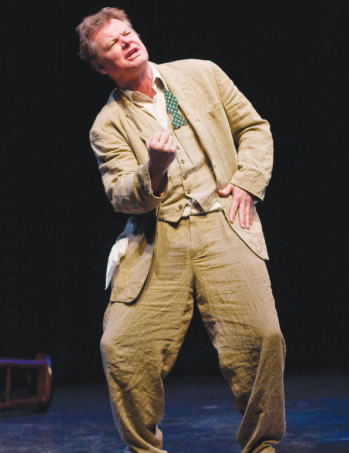

In the performance called “Do Not Go Gentle” now at the Harold Clurman on Theatre Row, there is a slightly different approach. Dylan Thomas, in the person of Welsh-Canadian actor Geraint Wyn Davies, leads off with another great poem, “In my craft or sullen art,” and then dryly adds: “Some time after I wrote that…I died.”

The quip was put into Davies’s mouth not by Dylan Thomas but by another talented Welsh Canadian: poet-playwright-director Leon Pownall, himself dead three years now. “Do Not Go Gentle” is a solo (though multi-layered and wide-ranging, you can’t really call it a play) that Pownall and protégé Davies had worked on, at intervals, since the mid-1980s

It had a brief New York exposure five summers ago at the Arclight Theatre in the basement of the Church of the Sacred Sacrament on West 71st Street, at which time this theatergoer summed it up as “Dylan Thomas on the whole shell.” Now, second time round, it is all of that and considerably more.

It presents a Dylan driven by hunger for women, by fear of women (wife Caitlin not least), by fear and disgust over his own physical lumpiness, by the debilitation of a poet’s eternal wrestling match with words, images, the language; most of all, perhaps, by the more particular wrestling match with the one mortal opponent he will never be able to beat:

“The Bard of you know where…And he’s the one I have to live up to, or, as in my case, die up to. Shakespeare. There’s a writer for you…And the Bard of Avon rules over my throbbing brain, and here I am in envy of some greatness. Will’s little helper.”

America, America!

America and Dylan Thomas were inseparable. A kid from Minnesota named Bobby Zimmerman even changed his name to Bob Dylan out of worship for a supreme wordsmith.

I was a big hit in America. Boffo, as they say. The matrons of America housed me and aroused me, fed me and led me…lodged me and dodged me…

It was at the start of his fourth and final tour of America that Dylan Thomas collapsed in the Hotel Chelsea on West 23rd Street and was taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where, on November 9, 1953, death reasserted its dominion. The funeral, at the Church of St. Luke in the Fields, on Hudson Street, was — this scribbler was there — deeply moving.

Geraint Wyn Davies, the Dylan of Theatre Row’s “Do Not Go Gentle,” has spent time acquainting himself with Dylan’s New York haunts — the White Horse Tavern (a few blocks north of St. Luke’s on Hudson Street) and other favorite bars, some “little park-ettes down in the Village,” and, of course, the Hotel Chelsea itself.

Did you have a beer at the White Horse Tavern, Geraint?

“Did you say a beer?”

Ruddy, blue-eyed Wyn Davies, an actor whose credits, Shakespearean and otherwise, run from here to St. Swithin’s Day, was born in Swansea, South Wales — Dylan’s own point of origin. Geraint’s father is a Welsh Congregationalist minister, his mother a retired teacher, his brother “a bush pilot in Thailand.” When Geraint was 7, the family migrated to Canada, which has been his homeland ever since.

It was as fellow actors in the 1980 Shaw Festival at Niagara-on-the-Lake that Geraint Wyn Davies met and became friends with Leon Pownall, who had been working on a stage portrait of Dylan Thomas for some time.

“He had me do a reading of it at the Stratford [Canada] Festival in 1985. I was too young,” says Wyn Davies candidly. “No way I could rise to the challenge. Leon said: ‘When you’re ready…”

“Ah, to hell with death! Let’s talk about the ladies, God bless ’em! I’ve always had my way with the ladies. A real clever Dick I am. They couldn’t keep their hands off me. Wanted to see if I had one. Well I did! And I put it in every cul-de-sac from Lands End to John-O-Groats.”

Or from Greenwich Village to Beverly Hills and back.

This show, you might say, if you were Dylan Thomas, is not for the towering dead…

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.