By MATT HARVEY

GENIUS AND HEROIN

Harper; 368 pp.; $15.95 (paperback)

On a recent cold, gray, afternoon, Michael Largo, a late-middle-aged author of three encyclopedias on death and madness, took a walking tour of sorts around the East Village. “Genius and Heroin,” his latest volume of a loose trilogy on the two titled themes, was inspired by the years he lived in the neighborhood, hanging out with Gregory Corso and other protégés of beat eminence, William Burroughs.

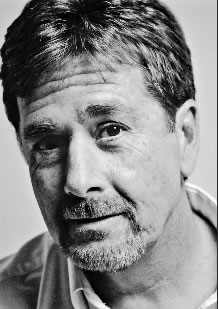

Largo, a compact man with a gray-flecked auburn goatee, spent the 1980s owning and operating the legendary St. Marks Grill, which sat on the corner of St. Marks and First Ave. Since then, the generic black canopy façade of the lounge Tribe has erased all evidence of his bar; it served as a louche retreat for Joni Mitchell, pop art “godfather” Larry Rivers and—for a short time—Keith Richards. (The Rolling Stones used the Grill as the setting for their video of “Waiting on a Friend,” their jazzy portrayal of coolly anticipating the drug connection.)

“The first thing Keith asked me when he came into the bar was ‘Where can I cop?’” Largo said, perfunctorily tossing off a worn over anecdote. “My liquor license is right above my head and cops and producers are around.” A smile crept to his lips, as he continued. “I said, ‘Here’s a bottle of Jack, that’s all I can help you with.” His barroom charm managed to infuse his name-dropping with some life.

Twenty-five years, and several layers of gentrification later, Largo—who moved to Miami in 1990 and stayed there—couldn’t find his bearings in his old neighborhood. His usual wry grin turned slack and he said; “Back then this whole area was just people who were into art and you know…” His soft, Staten Island-accented voice broke up into a slightly sinister laughter.

Largo, the son of an NYPD narcotics detective, went on to clarify that his interest in his subject wasn’t purely academic. In his words, he did “two levels of research” for “Genius and Heroin.”

“The last 10 to 15 years were spent in libraries. Sometimes I wouldn’t eat,” he explained in a monotone patter. “Before that I was living it, you know?” His research methods aren’t as overzealous as they sound. All three reference books are at least 350 pages and he has put them all out since 2006. (“The Portable Obituary,” and “Final Exits,” both A to Z guides to fame and death, came before “Genius and Heroin.”)

There is an obsessive quality to Largo’s fascination with the twin tropes of death and insanity. “It’s a substitute for the drugs and booze—you’ve got to have substitutes,” he said. For the newest book, Largo was interested in the medicated sweet spot where the drug addicted “genius” can find his voice and thrive creatively, or, as he says: “The guys who were trying to stay on that line and make it work.”

As we stood at the southeast corner of Tompkins Square Park, on Charlie Parker Place, chatting about the relationship between be-bop and heroin, Largo conceded that he did not have Parker’s white acolyte—and hopeless addiction casualty—Chet Baker in his latest compendium. In Largo’s lexicon, heroin “is just a synonym for reckless abandon,” and drug addicts and alcoholics are lumped together with a potpourri of disorders: gluttons, epileptics and in Flaubert’s case, according to “Genius,” a bromide abuser and S&M fetishist. Odder still, Burroughs and Miles Davis—two of the most prolific heroin addicted artists of all time—are only given as much space as the actors Heath Ledger and John Candy, respectively, the latter for his eating habits.

Largo is at his most creative and entertaining when whimsically noting obscure curios about the addiction sub-culture, like the history of speedballs or how syringes of the rich were decorated in the late 19th century. He writes describing the rehabs of yesteryear. “Patients were subdued with ample amounts of morphine, giving the hallways a church like quietude.” The sentence reads as if its been culled from a detoxing addict’s daydreams. But compulsive curiosity does not an artist make and Largo lacks the discipline needed to write a good reference book. I couldn’t help but sense the iron hand of contractual obligation in “Genius and Heroin,” a shame given Largo’s respect for the material.

Near Second Avenue, a broken-down figure bundled up in a tweed overcoat asked Largo for some change. He noticed that the man—who introduced himself as, Angelo, a homeless heroin addict—had the letters “A-T-E” tattooed across his left knuckles. “It used to say ‘hate,’ but I scraped the h off,” Angelo said. “To the bone.” Then he held his knuckles up for inspection and added, “I felt relieved.”

Largo held the man in a streetwise gaze and asked him what he used to dull the pain of the procedure.

“Nothing, I did it straight,” he replied.

Angelo’s account of the pain he underwent to erase a reminder of a past that haunted him was cringe-inducing. I looked to Largo, but he responded with an impassive “Cool.” The bum was a much more powerful portrayal of the self-constructed prison cell of opiate addiction than the author’s hagiographic concept of “wild abandon” found in “Genius and Heroin.” After all his years of immersing himself in the subject, Largo misses what opiate addicted geniuses like Charlie Parker or William Burroughs always knew; great art is created in spite of drugs, not because of it.